This rich book explores the links between Irish periodical journals of the twentieth century and journalism. This is a handsomely-produced volume and it is good to see academic commentaries sitting comfortably beside those of practicing journalists and independent scholars, writes Carole O’Reilly.

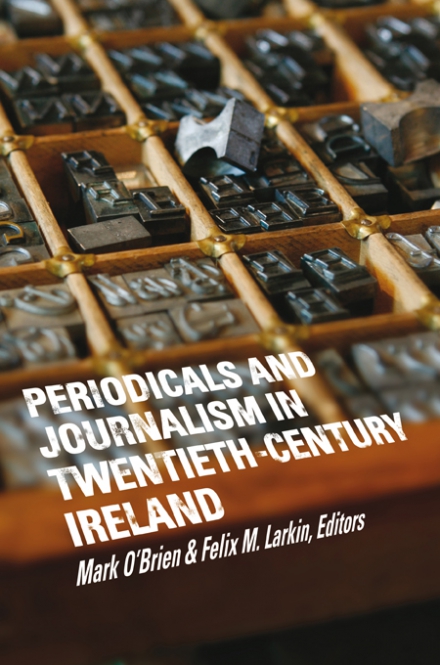

Periodicals and Journalism in Twentieth Century Ireland. Mark O’Brien and Felix M. Larkin (eds.) Four Courts Press. 2015.

Periodicals and Journalism in Twentieth Century Ireland. Mark O’Brien and Felix M. Larkin (eds.) Four Courts Press. 2015.

This lively collection of 14 essays is a welcome contribution to the study of newspapers and periodicals in Ireland. It represents the fifth volume of research by members of the Newspaper and Periodical History Forum of Ireland, formed in 2008.

The book addresses the emergence and development of a wide range of popular periodicals from the suffragette-supporting The Irish Citizen to the religious periodical The Furrow and the contemporary music magazine, Hot Press.

As the introductory essay by the editors points out, these publications offered an alternative view of life in the Irish republic during the turbulent twentieth century and thus fulfilled an important social and political purpose. Many operated in very straitened financial circumstances and were impacted upon by the political situation, both pre- and post-independence. The significance of these magazines did not lie only in their content or production. They were mostly edited by forceful and interesting personalities, many of whom are brought to life here. This is a strength of the collection – the emergence of the often shadowy figures of those who edited and wrote for these publications. Inevitably, most are fairly high-profile journalists and writers but these are the kinds of people about whom much is already known and written.

A chapter by Colum Kenny focuses on Arthur Griffith, who was associated with a variety of publications in the early years of the twentieth century. Griffith began his career as a copyeditor and compositor in an age when the journalism and printing professions frequently overlapped quite harmoniously. He learned his editing skills during a spell in South Africa, where he had emigrated in an attempt to mitigate his tuberculosis. He returned to Dublin to edit the United Irishman in 1899. This role, as was common at the time, combined writing for and editing the paper with its management, a fusion of creative and financial roles. Kenny notes that Griffith did much to encourage female contributors to the United Irishman, a reflection of his belief in the equality of the sexes and a desire to enrich and diversify the content of his magazine.

Like many small publications, the United Irishman was vulnerable to legal actions and was closed as a result of a libel case against a parish priest, Father Michael Donor, in Limerick in 1906. Griffith was described in court by Donor’s counsel as ‘the Pooh-Bah of the establishment – director, manager, editor and libeller’ (p. 22), which gives an intriguing insight into his character. The remainder of his journalistic career was spent on a succession of periodicals, many of which were short-lived but all were devoted to Griffith’s interest in social justice. The British government suppressed many, always sensitive to criticism in print. Griffith was eventually elected to the Irish parliament in 1918, following a conspicuous tradition of British journalists during this period.

Sonja Tiernan’s chapter on the suffragette magazine The Irish Citizen offers a portrait of a successful political and campaigning periodical established by the Irish Women’s Franchise League in 1912. The many parallels in suffrage activity between Britain and Ireland are noted and the magazine contained frequent articles on suffrage activities in both countries. After one month of publication, the Irish Citizen had a circulation of around 3,000 copies, sufficient to be considered a success. The periodical also had a tradition of strong female editorship from 1915, when Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington took over from her husband, Francis. Francis was imprisoned for six months with hard labour for organising and speaking at anti-military meetings in Dublin after the beginning of the First World War. Financial struggles were again apparent here and the initial eight pages had to be reduced to six in early 1916. The Easter Rising diminished the paper’s contributors in 1916, when many were killed, injured or imprisoned. Francis Sheehy-Skeffington was executed in April after returning from a meeting of the Irish Women’s Franchise League (notably along with two other newspaper editors). A succession of female editors (including Hanna) continued the paper until its closure by the British auxiliary force (the Black and Tans) in 1920, when its printing presses were destroyed. This was a common method of discouraging certain politically-motivated publications but the Irish Citizen had escaped this punishment for a comparatively long time.

Joe Breen’s analysis of the music and political periodical Hot Press offers a much-needed opportunity to reflect on its contribution to Irish life at a turbulent time – the influence of the Catholic church was commencing its decline, a young urban population was beginning to emerge and social and political upheaval was common. Clearly modelled on America’s Rolling Stone, Hot Press began publication in 1977 and established itself firmly in the tradition of underground publications of the 1960s. Originally set up to promote Irish-produced music (especially U2), it quickly mutated into a broader commentary on Irish political life. Flagship political interviews sat alongside music reviews and often threatened to overwhelm them during the 1980s in particular. A controversially candid interview with then-Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Charles Haughey in 1984, dominated by his use of colourful language and often visceral denunciation of his political enemies, brought the magazine to a wider audience and confirmed its place as ‘the de facto print media voice of the rock ‘n’ roll generation’ (p. 212). Hot Press continues to be edited by its founder, Niall Stokes, and has managed to survive the digital threat by expanding onto the web with a degree of success. For consistency and dogged persistence, it would be hard to find another magazine still in publication, which has clung so firmly to its original mission.

This is a handsomely-produced volume and it is good to see academic commentaries sitting comfortably beside those of practicing journalists and independent scholars. Only one chapter in the text has illustrations, which is something of a disappointment when examining such visually rich material as periodicals. I can only assume that cost was a factor in this decision, a sad reflection of the continuing, limited budgets for this kind of expense.

Carole O’Reilly is Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at the School of Arts and Media, University of Salford. Her main research interests lie in journalism history and the social role of public space in the urban environment. She can be found on Twitter @caroleoreilly. Read more reviews by Carole.