In The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and its Aftermath, Dan Stone explores the deconstruction of the Nazi camp network. Drawing upon diaries and interviews yet also attentive to the unfolding geopolitics of the post-war years, Stone offers an important account of the complex journey from prisoner to survivor experienced by those freed from the camps, writes Mahon Murphy.

The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and its Aftermath. Dan Stone. Yale University Press. 2015.

André Singer’s documentary Night Will Fall, screened earlier this year on Channel Four, not only encapsulates the horror of the conditions of the Nazi-run concentration camps, but also the difficulty of creating an official account of the camps that can slot neatly in with the Allied narrative of World War Two as a whole. Liberation from the camps did not mean the end of the horrors of the Holocaust. Dan Stone’s new book, The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and its Aftermath, maps the experience of survivors and forces us to look beyond the end of the war, offering an important contribution to our understanding of the difficulty and long-term psychological effects of deconstructing the Nazi camp network.

André Singer’s documentary Night Will Fall, screened earlier this year on Channel Four, not only encapsulates the horror of the conditions of the Nazi-run concentration camps, but also the difficulty of creating an official account of the camps that can slot neatly in with the Allied narrative of World War Two as a whole. Liberation from the camps did not mean the end of the horrors of the Holocaust. Dan Stone’s new book, The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and its Aftermath, maps the experience of survivors and forces us to look beyond the end of the war, offering an important contribution to our understanding of the difficulty and long-term psychological effects of deconstructing the Nazi camp network.

The survivors faced years of further struggles to find a place to call home and to rebuild their lives. Those who moved to the UK or the USA found their experiences subsumed in the general narrative of war suffering. The surviving victims of Nazism would have to wait many years before the liberating powers began to comprehend the Holocaust. Allied policy towards Jewish displaced persons, as Stone shows, only exacerbated the problem of mutual misunderstanding and the difficult and traumatic experience of being freed from Nazi extermination camps.

Part of the problem was that the US and British authorities found it very difficult to understand the crucial differences between the camps they had liberated in Western Europe and those that the advancing Red Army had freed in the East. The Western Allies distrusted the official Soviet reports on the camps, with the majority of the British press mentioning Soviet descriptions of the atrocious conditions of the camps and the industrialised slaughter that took place in them with a tone of disbelief. Nazi death camps were played off as a piece of Soviet propaganda. This would change for the British with the ‘discovery’ of Buchenwald, Dachau and Belsen. Suddenly the Soviet’s descriptions of Majdanek and Auschwitz were all too real.

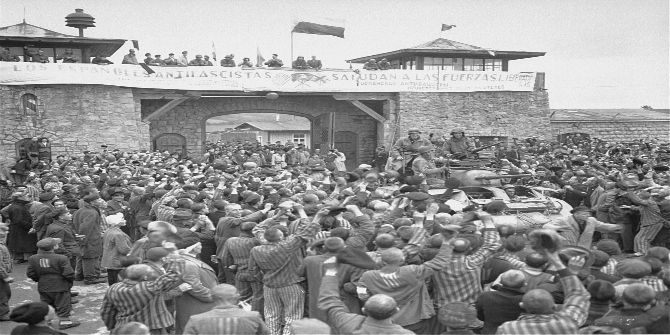

Image Credit: Tanks of the US 11th Armoured Division entering the Mauthausen concentration camp; banner in Spanish reads ‘Antifascist Spaniards greet the forces of liberation’. 6 May 1945 (Wikipedia Public Domain)

Image Credit: Tanks of the US 11th Armoured Division entering the Mauthausen concentration camp; banner in Spanish reads ‘Antifascist Spaniards greet the forces of liberation’. 6 May 1945 (Wikipedia Public Domain)

Stone situates the events surrounding the liberation of the camps not just in the long coda to the Holocaust, but also as fundamental to the unfolding post-war years in Europe, the geopolitics of the Cold War and, due to the significance of these events for Palestine, to the future of the British Empire and the Middle East. The liberation of the camps constitutes a bridge between the war years and the post-war period.

However, Stone does not merely offer a political account of the liberation of the camps and the decisions made, wisely or unwisely, by the British, US and French authorities. Through the retracing of diaries and interviews, he presents the very human dimension to the liberation of the camps. With this vast amount of oral history, Stone uses accompanying official reports, journalistic accounts and statements by liberating soldiers and relief workers. While he agrees that the Holocaust will always remain opaque in our understanding, he goes a good way towards giving the reader a sense of what liberation was like for those who experienced it.

The stories of the survivors highlight how sudden and unexpected liberation was. The common perception, as propagated in recreated Soviet films of liberation, is one of joyous scenes. The reality, however, was often less dramatic. The camp network was vast. For those in hiding, in forced labour camps outside the main SS camp system and others attached to sub-camps, the Holocaust ended in ‘ordinary’ (if one can use the term) or non-dramatic ways. The moment of liberation, as Stone shows, was not one of complete joy, but rather a moment of mixed emotions and confusion.

After covering the initial moments of liberation, Stone moves on to the longer-term effects. The question of how to feed, organise and eventually repatriate so many thousands of former camp inmates was a gargantuan task, and one in which the significant fact that Jews had been particularly targeted by the Nazi regime got lost. For the Soviets, the fact that the victims of the death camps had been predominantly Jewish was of little ideological use. The war for the Red Army was, after all, the defeat of Fascism and the total victory of the international working class. Representing the victims of the Nazi regime as people who died in the name of the anti-Fascist cause, while noble, was to miss the point that the Nazis’ primary victim group had been targeted on racial grounds.

That there were Jewish displaced persons still being held in camps in Germany in 1952 serves to hammer home the difficult and traumatic process of repatriating a people who were often German-born. Anti-Semitism did not, of course, end with the war and the Jewish populations of the displaced persons camps were still often subject to abuse. While the Jewish inmates of these camps naturally wished to get out of Germany and away from the site of terrible atrocities, some displaced persons were still being housed in former camps, most notably Belsen. Tracing their journey from Germany to Israel, Stone’s narrative shows the shocking conditions that those who were ‘liberated’ were forced to endure.

The stories of Holocaust survivors that Stone relates remind us that their futures lay very much in the hands of others, and those who were making decisions were increasingly under pressure to adhere to the requirements of Cold War politics. The Palestine question was connected to US immigration policy and Soviet attempts to disrupt the British Empire. Finally, this was enmeshed in the emergence of Konrad Adenauer’s West Germany. It was, as Stone notes, a toxic brew. The journey from prisoner to survivor was extremely long and painful and, as this book shows, liberation of the camps in 1944/45 was only the beginning of a process that would take years to complete.

Publications on the Holocaust and its connection to the Third Reich concentration camp system remain a constant. Nikolaus Wachsmann’s recent and well-received publication KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps (2015) has provided a detailed map of the development of the concentration camp from the beginning to the end. Dan Stone’s The Liberation of the Camps expertly takes up this thread, offering a fascinating account of what happened to Holocaust survivors once freed from the death camps in which they were held.

Mahon Murphy is a PhD candidate in the History department at the LSE where he also received his MA. His research is on German prisoners of war and civilian internees in the extra-European theatre of the First World War. His thesis looks at the treatment of European prisoners in a colonial context with a focus on the fall of the German colonies and protectorates in Africa, China and the Pacific. Read more reviews by Mahon Murphy.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.