In Iberian Military Politics: Controlling the Armed Forces During Dictatorship and Democratisation, José Javier Olivas Osuna traces the divergent trajectories of civil-military relations in Portugal and Spain from the 1930s to the 1980s. This book offers a convincing challenge to the idea of a shared Iberian pathway through dictatorship and democratisation, finds Alejandro Quiroga.

Iberian Military Politics: Controlling the Armed Forces During Dictatorship and Democratisation. José Javier Olivas Osuna. Palgrave Macmillan. 2015.

When comparing the regimes of Francisco Franco and António de Oliveira Salazar, scholars have often highlighted ideological, political and organisational similarities between the dictatorships. Likewise, political scientists and historians have contrasted the Portuguese and Spanish transitions to democracy in the 1970s, frequently presenting both cases as relatively peaceful, elite-driven, successful models. On some occasions, the comparisons between Spain and Portugal have led academics to discuss the existence of a common ‘Iberian ethos’ that would explain historical parallels. José Javier Olivas Osuna’s Iberian Military Politics: Controlling the Armed Forces During Dictatorship and Democratisation challenges the very idea that Spain and Portugal had common historical trajectories, let alone a joint ethos. Olivas Osuna argues that no clear ‘Iberian style’ or ‘Iberian path’ can be identified when comparing civil-military relations from the 1930s to the 1980s (11). All things considered, discrepancies outweigh similarities.

When comparing the regimes of Francisco Franco and António de Oliveira Salazar, scholars have often highlighted ideological, political and organisational similarities between the dictatorships. Likewise, political scientists and historians have contrasted the Portuguese and Spanish transitions to democracy in the 1970s, frequently presenting both cases as relatively peaceful, elite-driven, successful models. On some occasions, the comparisons between Spain and Portugal have led academics to discuss the existence of a common ‘Iberian ethos’ that would explain historical parallels. José Javier Olivas Osuna’s Iberian Military Politics: Controlling the Armed Forces During Dictatorship and Democratisation challenges the very idea that Spain and Portugal had common historical trajectories, let alone a joint ethos. Olivas Osuna argues that no clear ‘Iberian style’ or ‘Iberian path’ can be identified when comparing civil-military relations from the 1930s to the 1980s (11). All things considered, discrepancies outweigh similarities.

The book sets out a political science comparison of civil-military relationships in Spain and Portugal during Franco’s and Salazar’s dictatorships and the subsequent transitions to democracy. Olivas Osuna focuses on the policy instruments or ‘tools of control’ that governments make use of to keep the military in check. By concentrating on these ‘tools of control’, Iberian Military Politics comprehensively shows what governments actually did to monitor the military.

Concurrent to this approach, the author applies an adapted model of Christopher C. Hood’s ‘NATO scheme’ for the study of the tools of government. ‘NATO’ here is an acronym of ‘nodality, authority, treasure and organisation’: four resources related to communication channels, legal power, money and people and equipment respectively, from which policy instruments draw their power. Olivas Osuna analyses both the Portuguese and the Spanish governments’ strategies for military subordination according to Hood’s four basic resources, outlining the most significant tools and the main trajectories observable in their usage.

Iberian Military Politics also draws on neo-institutionalist scholarship. It explores civil-military relations by focusing on the role of ‘historical causes’ and ‘constant causes’. Thus, the availability, desirability and use of the ‘tools of control’ are examined in relation to both ‘macro historical events’ and ‘constant environmental factors’. Macro historical events refer to events including the rise of Fascism, the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, NATO and colonial conflicts, whereas constant environmental factors take the shape of actors, institutions and ideologies. Combined with Hood’s ‘NATO scheme’, the historical comparison allows Olivas Osuna to develop a cogent theoretical model that tackles the issue of civil-military relationships in a broad manner.

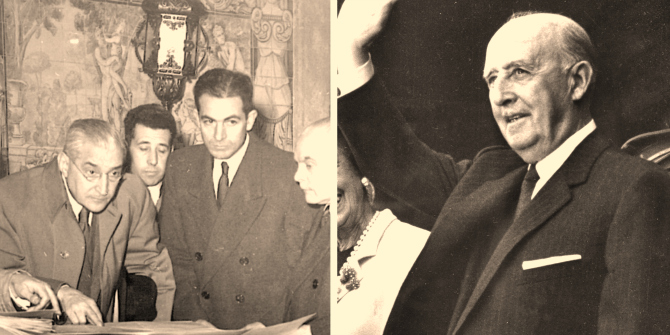

Image Credit: António de Oliveira Salazar, 1954 (Wikipedia Public Domain) and Francisco Franco, 1968 (Wikipedia Public Domain)

Image Credit: António de Oliveira Salazar, 1954 (Wikipedia Public Domain) and Francisco Franco, 1968 (Wikipedia Public Domain)

Following an introductory theoretical section, the book is divided into three main parts. The section on Portugal examines both the Salazar-Caetano dictatorship and the transition to democracy sparked off by the Carnation Revolution. Interestingly, the revolutionary provisional government created in April 1974 took a similar approach to that of the Estado Novo regime when it came to controlling the military insurrections, using a new series of coercive organisational tools. After the November 1975 left-wing coup attempt, however, important efforts to depoliticise the military and demilitarise politics were made. Through joint exercises with NATO allies, a modern military education, the end of censorship and the promotion of free media, governments fostered a new doctrine to persuade the Portuguese army of the benefits of subordination to civilian rule. By 1982, the Council of the Revolution had been abolished and a new constitution certified the principle of civilian supremacy.

The section on Spain explores civil-military relations during the Franco dictatorship and the transition to democracy. Unlike its Portuguese counterpart, the Spanish military never challenged the dictator. After all, Franco was a general who formed his military dictatorship in the midst of a civil war. Military officers kept high-ranking posts in the state apparatus and the army remained a key element for domestic repression throughout the entire dictatorship. The central role of the army and the cohesive, far-right ideology of the Spanish military became a serious problem for Francoist reformers once the dictator died. In the early years of the transition, the military top brass showed their reluctance to undertake democratic reforms and many of them aligned with Francoist civilian hardliners.

Olivas Osuna perhaps exaggerates the people’s desire for democracy by the time Franco died, as he considers that ‘there was a majoritarian belief in Spanish civil society of the necessity of a democratic system’ (121). As a matter of fact, opinion polls of the time show that Spaniards prioritised ‘order and peace’ over democratic values. But whatever the Spaniards’ level of commitment to democratic principles, the truth of the matter is that Francoist reformers, such as PM Adolfo Suárez and General Gutiérrez Mellado, sought and reached an agreement with the democratic opposition to create, gradually, a parliamentary monarchy. Many military officers disliked the idea. Others openly plotted to prevent the establishment of a democratic system. Between 1978 and 1985, Spanish governments faced a number of cases of military insubordination, conspiracies and failed coups. General Franco cast a long, dark shadow over the new Spanish political system. It was only with the reforms of the first socialist government (1982-86) that full military subordination to civilian power became a reality.

The final section of the book is entitled ‘Comparisons and Explanations’. It contrasts Portuguese and Spanish trajectories in tool choice and civilian-military relationships. Olivas Osuna argues that ‘macro historical events’ and ‘environmental factors’ determined these trajectories. To his credit, the author acknowledges that macro-historical events and environmental factors are often interwoven. Sometimes, macro-historical events, like the Spanish Civil War, created critical junctures in environmental factors, such as the ideology of Franco’s dictatorship. On other occasions, environmental factors, such as fascist ideology, were at the origin of macro-historical events, for instance, the Second World War. At times, it is difficult to tell which came first: macro-historical events or environmental factors. This recognition of the intricate intertwining of macro-historical events and environmental factors should not be read as a weakness in Olivas Osuna’s theoretical model. It rather shows the flexible and multifaceted nature of the book’s neo-institutionalist approach when exploring complex historical problems.

Iberian Military Politics is not always an easy read. The political science analysis is at times dense, and a reader not familiar with the period may feel a bit lost in the twists and turns of Spanish and Portuguese history. Yet the book convincingly challenges the idea of a common Iberian path, debunking well-established beliefs about Spanish and Portuguese shared historical trajectories. And this is, after all, what a good academic book is supposed to do.

Alejandro Quiroga is a Reader in Spanish History at Newcastle University, UK. He specialises in the study of national identities and nationalisms. His most recent book is Football and National Identities in Spain (Palgrave, 2013). He is also the author of The Reinvention of Spain. Nation and Identity Since Democracy (Oxford UP, 2007) (with Sebastian Balfour), Making Spaniards. Primo de Rivera and the Nationalization of the Masses, 1923-1930 (Palgrave, 2007) and Los orígenes del Nacionalcatolicismo (Comares, 2006). He has edited Right-Wing Spain in the Civil War Era. Soldiers of God and Apostles of the Fatherland, 1914-45 (Continuum, 2012) and Católicos y patriotas. Religión y nación en la Europa de entreguerras (Sílex, 2013).

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments