In this feature essay, Sundari Anitha and Ruth Pearson introduce their new book, Striking Women: Struggles and Strategies of South Asian Women Workers from Grunwick to Gate Gourmet, which focuses on two industrial disputes in the UK: the famous Grunwick strike (1976-78) and the Gate Gourmet dispute of 2005. The book, which is being launched at SOAS, University of London, on Thursday 26 April 2018, gives a voice to the women involved in the strikes and explores South Asian women’s contribution to the struggles for worker’s rights in Britain.

If you are interested in this book, you may also want to visit the interactive website www.striking-women.org, created by the authors for schools and community groups and offering resources on migration, women’s and labour rights based on research on South Asian women in the UK.

Striking Women: Struggles and Strategies of South Asian Women Workers from Grunwick to Gate Gourmet. Sundari Anitha and Ruth Pearson. Lawrence and Wishart. 2018.

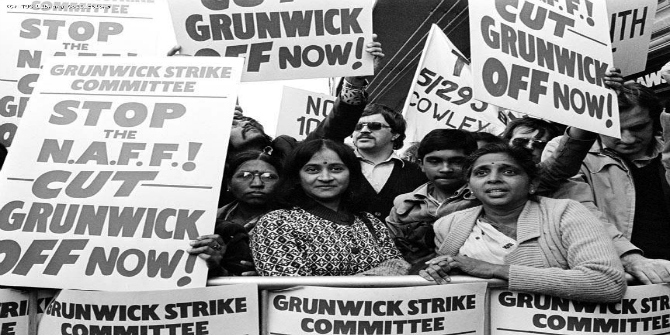

2018 marks the fortieth anniversary of the end of the emblematic Grunwick strike, an event which is writ large in the annals of British trade union history. Grunwick is still remembered as the moment when the trade union movement took the cause of migrant and women workers to its heart. This was seen as the point at which intersectionality was embraced by organised labour in the UK, which led to the espousal of anti-racist policies and an end to support for the privileges of the male labour aristocracy – either as breadwinners or as full-time established workers.

2018 marks the fortieth anniversary of the end of the emblematic Grunwick strike, an event which is writ large in the annals of British trade union history. Grunwick is still remembered as the moment when the trade union movement took the cause of migrant and women workers to its heart. This was seen as the point at which intersectionality was embraced by organised labour in the UK, which led to the espousal of anti-racist policies and an end to support for the privileges of the male labour aristocracy – either as breadwinners or as full-time established workers.

However, the story is more complicated. Firstly, the Grunwick strike ended in defeat. The much-heralded and broad support for the mainly South Asian women strikers, most of whom were twice migrants from countries in East Africa, where they had settled during British colonial rule, evaporated in the face of a conservative union leadership and Trades Union Congress (TUC) yielding to fears about social unrest and political disaster in the dying days of the Labour government in 1977. As Jayaben Desai, the iconic strike leader, famously quipped:

Trade union support is like honey on the elbow – you can smell it, you can feel it, but you cannot taste it.

By March 1978 the mass pickets of the previous year had disappeared; the boycotting of the post by the Postal Workers’ Union, an effective tool to pressurise a mail order business, had been overruled; and the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (Acas)-appointed Scarman Inquiry, which found in favour of the strikers’ main demands for union recognition, collective bargaining and reinstatement, had been ignored by the litigious Anglo-Indian owner of Grunwick, George Ward. But the centrality of Grunwick to contemporary trade union narratives lives on.

Our new book, Striking Women: Struggles and Strategies of South Asian Women Workers from Grunwick to Gate Gourmet, interrogates this narrative. It focuses on the political and personal agency of the women strikers themselves, unlike previous accounts including Jack Dromey and Graham Taylor’s well-known Grunwick: The Workers’ Story (originally published in 1978 and republished in 2016 to mark the fortieth anniversary of the start of the strike), which predominantly concerns the itinerary of the industrial dispute, and Joe Rogaly’s Grunwick (1977). These earlier books rehearse the familiar story of how workers at the film processing plant in North West London were so exasperated and offended by the overbearing and arbitrary management that they walked out; how a small group of South Asian workers grew to a significant number under the leadership of the indomitable Desai, guided and supported by the Brent Trades Council, including the then-youthful Dromey. They recount how support for the strikers spread to other well-organised unions, including the National Union of Mineworkers and the previously protectionist and anti-immigrant London dockers, and how the strategy of mass picketing was supported not only by trade unionists up and down the country, but also by large sections of the left as well as the women’s movement and anti-racism activists.

The authorised story of the dispute, favoured by trade unions, does not dwell unduly on the ultimate defeat, or even the lack of sustained or robust commitment on the part of particular unions in the face of a changing political and economic landscape which saw the Labour government fall victim to heightened anti-union scapegoating. Instead it focuses on its trajectory, the escalation of the picketing, the details of the Scarman Inquiry and the tactics used by the Grunwick owner and his right-wing allies to outwit the actions of the wider labour movement to increase the pressure on the firm. But it says little about who the strikers were, how they experienced the long years of this dispute or what their lives were like before and after.

Striking Women, on the other hand, is rooted in the lived experience of the women strikers. Although the surviving Grunwick strikers were quite elderly when we undertook our initial research in 2007-10, we were able to interview four other South Asian women ex-strikers in addition to carrying out an extensive interview with Desai, who died in 2010. Because we were able to talk to the women in Hindi and sought the women’s work/life histories rather than just their memories of the strike and its aftermath, we captured a more nuanced understanding of their lives. We were able to access a broader account of how they were able to juggle their responsibilities at home with the requirements of their job, which reinforced the finding that one of the most unacceptable aspects of the harsh management regime at Grunwick was the imposition of arbitrary overtime which made it too difficult to manage these competing demands.

We also gained a deeper understanding of the intersecting dynamics of the situation these migrant workers were faced with as low-paid workers in an increasingly hostile country, working in a new, unregulated and unorganised industry. They had no previous experience of outside paid work or industrial militancy to fall back on, and having occupied an intermediate position in colonial East Africa, they were unprepared for the everyday or institutionalised racism of 1970s London in a country where they had expected to receive a citizen’s welcome. The managerial controls played on these gendered and racialised hierarchies to exercise maximum productivity from the workers. It is not surprising that in the years following the dispute, the actions of the striking women continued to be celebrated through what can be seen as an orientalist lens, as the media and others repeatedly expressed their surprise at these short and feisty ‘strikers in saris’: a view that reinscribes stereotypes of the passive South Asian woman.

The events of the Grunwick strike have been extensively analysed both by contemporary journalist and trade unions, as well as by historians and political scientists. In contrast to other accounts, however, our book does not stop at the end of the strike. Instead, it takes as its endpoint a second dispute involving migrant South Asian women workers some 30 years later at Gate Gourmet. Striking Women includes the first account of this struggle, based on the voices of the women involved. Drawing on life/work history interviews with 32 women who participated in the two disputes, as well as interviews with trade union officials, archival material and employment tribunal proceedings, we explore the motivations, experiences and implications of these events for strikers’ political and social identities.

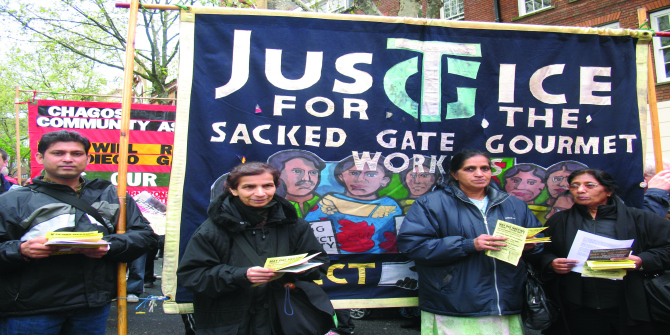

This was the Gate Gourmet dispute that erupted in 2005, involving primarily Indian migrant workers who were employed in the preparation of in-flight food. In contrast to the twice-migrant Grunwick workers from East Africa, the Gate Gourmet women were direct migrants from the Punjab, who came from non-English-speaking land-owning peasant families. Most of them had migrated to London as young women, either as daughters, fiancées or wives, and unlike the Grunwick strikers, they were members of a trade union (the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU)) and had decades of working experience in the London labour market, mainly as low-paid unskilled workers.

After Gate Gourmet obtained the contract for the production of in-flight meals following the outsourcing by British Airways in 1997, these workers experienced a continuing deterioration in their conditions at work, which they resisted with, and sometimes without, the support of their trade unions. In July 2005, in response to the imposition of non-unionised East European workers on their production line, the Asian women workers walked out to discuss the appropriate course of action with their union representatives. Acting on the advice of their shop stewards, they refused the management’s ultimatum that they return to work and were effectively sacked by megaphone.

Initially, other workers were supportive, and the TGWU brought the baggage handlers out in solidarity. But, as we detail in Striking Women, the world had changed since the 1970s. Secondary picketing had been outlawed, and worker’s grievances were mainly taken to a series of industrial and employment tribunals to be resolved. The secondary action was quickly called off as the union negotiated a Compromise Agreement with the employers, which saw the majority of the workers being reinstated under less beneficial terms and conditions, with a hand-picked number offered compulsory redundancy. These were generally older women or those who had needed to take sick or family leave in more recent years. When some 60 of them refused to accept the terms of the Compromise Agreement and established a protest demonstration on the nearby hill, trade union support ebbed away. A number of the sacked workers took their case to an employment tribunal, but the only workers who won their cases were the union shop stewards – the remaining workers were literally left out in the cold.

Many of these workers felt personally let down by their trade unions, and their experience of the lack of union support contrasts with the widespread support for the Grunwick strikers some 30 years earlier. The way in which the trade unions closed ranks and abandoned the women who refused to accept the compulsory redundancy spelt out in the Compromise Agreement was bitterly resented. Although the 2006 TUC Congress passed a unanimous resolution which expressed their ‘profound anger at the shameful treatment of those workers’ and called on members and affiliates to seek national and international support, asserting ‘their fight is our fight’ and promising to do their best to help these women workers, this was not what happened. Instead, they were abandoned by the union and lost their tribunal case on the grounds that they were taking unofficial strike action at the time of their dismissal. In contrast, the TGWU made a £600,000 settlement with the two shop stewards who were responsible for the ‘illegal’ secondary action by baggage handlers at Heathrow airport. In the end, the trade union movement walked away from these women, and they are not included in the list of honourable struggles for justice for minority and women workers in the UK.

The focus on these events throws light on the complex but continuing nature of South Asian women’s contribution to the struggles for workers’ rights in the UK. By examining the histories of migration and settlement of these two different groups of women of South Asian origin, we reveal how this history, their gendered, classed and racialised inclusion in the labour market, the context of industrial relations in the UK in the two periods and the nature of the trade union movement shaped the trajectories and outcomes of the two disputes.

The strikes also serve as a prism for examining particular continuities and changes in industrial relations, trade union practices and their scope for action. This book challenges stereotypes of South Asian women as passive and confined to the private sphere, whilst exploring the ways in which their employment experience interacted with their domestic roles. Paying close attention to the events and contexts of their workplace struggles enables us to understand the centrality of work to their identities, the complex relationships between these women and their trade unions and some of the challenges that confront trade unions in their efforts to address issues posed by gender and ethnicity. This is the workers’ story, not just the union’s story.

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image One Credit: Grunwick strikers picketing 1977 © TUC Library Collections, part of Special Collections at London Metropolitan University.

Image Two Credit: Sacked Gate Gourmet workers, May Day rally, London, 2008 © Sundari Anitha.

2 Comments