In Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s, Noni Stacey shows how a 1970s network of London-based photography collectives raised fundamental questions about the politics of photography, the role and responsibilities of photographers in relation to local communities and the uses of photography in the context of social activism. This book is a welcome addition to the expanding field of research on the photography of protest, writes Mathilde Bertrand, contributing to the ongoing documentation of this strong current in British photographic history.

If you are interested in this book review, you can read an LSE RB interview with author Dr Noni Stacey. The archive of the Exit Photography Group is held at LSE Library; readers can find out more about the archive and the catalogue.

Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s. Noni Stacey. Lund Humphries. 2020.

Over the last decade, the 1970s and 1980s in the history of British photography have generated renewed interest among the general public, in art galleries and across the fields of photographic and social history, cultural and social movement studies. The popular success of the online exhibition platform British Culture Archive, with over 50,000 followers on Twitter, demonstrates an enthusiasm for the exploration and rediscovery of the visual culture and photographic practices of the era. Scholars have explored the context of emergence of an independent photography sector in the UK and aspects of practice (see Siona Wilson, Daniel Palmer, Steve Edwards, Na’ama Klorman Eraqi), while individual and collective exhibitions and publications have showcased the work of photographers active in the period (the Side Gallery, the Martin Parr Foundation, El Museo Reina Sofia, The Midlands Arts Centre, Four Corners Gallery, The Café Royal Books collection, to name only a few). Galleries and libraries have archived and, where possible, endeavoured to digitise photographic collections (for example, the Four Corners Gallery, the Bishopsgate Institute and Photo Archive Miners).

Over the last decade, the 1970s and 1980s in the history of British photography have generated renewed interest among the general public, in art galleries and across the fields of photographic and social history, cultural and social movement studies. The popular success of the online exhibition platform British Culture Archive, with over 50,000 followers on Twitter, demonstrates an enthusiasm for the exploration and rediscovery of the visual culture and photographic practices of the era. Scholars have explored the context of emergence of an independent photography sector in the UK and aspects of practice (see Siona Wilson, Daniel Palmer, Steve Edwards, Na’ama Klorman Eraqi), while individual and collective exhibitions and publications have showcased the work of photographers active in the period (the Side Gallery, the Martin Parr Foundation, El Museo Reina Sofia, The Midlands Arts Centre, Four Corners Gallery, The Café Royal Books collection, to name only a few). Galleries and libraries have archived and, where possible, endeavoured to digitise photographic collections (for example, the Four Corners Gallery, the Bishopsgate Institute and Photo Archive Miners).

These initiatives across academia and the gallery world contribute to shedding light on the crystallisation and development of a radical visual culture combining socially engaged photographic practices and theoretical discourses on the photographic image in the 1970s. A politicised generation of young professional photographers was determined to place photography at the service of oppositional causes at a local, national and international level. Subsumed under the term ‘community photography’, different forms of political interventions through photography were experimented with and developed, guided by the aim of facilitating access to cultural expression and generating empowering uses of the camera.

Noni Stacey’s Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s, deals precisely with this moment in British photographic culture. The book is a welcome addition in this expanding field of research on what the author calls a ‘photography of protest’. The focus of the book is on five photographic organisations formed in London in the 1970s, highlighting how a small yet close network of professional photographers raised fundamental questions about the politics of photography, the role and responsibilities of photographers in relation to local communities and the uses of photography in the context of social activism. Stacey’s research contributes to the ongoing documentation of this strong current in British photographic history which spawned counter-cultural and agitational photographic practices rooted in collaborative working methods.

Drawn from Stacey’s doctoral thesis, enriched with interviews with key actors and numerous photographs gathered from various personal and institutional archives, the book offers a compelling micro-history of the Half Moon Photography Workshop, the Exit Photography Group, the Hackney Flashers Collective, the North Paddington Community Darkroom and the Blackfriars Photography Project, while never losing sight of the wider national context. The author exploits primary documents from varied sources: archival material, reviews of exhibitions in the press and articles from the specialist magazines Creative Camera and Camerawork, where debates on the politics of photography and the transformation of photographic practices were rife.

Not all of these groups were, strictly speaking, structured as collectives in the status that they chose to adopt (contrary to what the book’s title suggests), yet their values, principles and methodologies, their efforts to mutualise resources, skills and energy, were definitely driven by a desire to seek collective and collaborative alternatives in a professional sector which valued high-profile individuals of the ‘lone photographer’ type. Against this tendency, and as a political gesture, the photographers involved in the formation of these groups chose to work together in ways which reflected their values and their shared political commitments on the left of the political spectrum – a process which wasn’t without friction. Membership overlapped as photographers navigated the same circles, exchanged ideas, working practices, resources and outlets, or went on to pursue projects in recomposed formations.

The first chapter is dedicated to the activities of the Half Moon Gallery, which became the Half Moon Photography Workshop in 1975, and its bonds with the radical history of the East End and its vibrant culture of resistance and organisation. The gallery, which also set up a community darkroom and organised regular seminars open to all, was an active participant in the local community’s struggles against poor housing conditions, unemployment as well as race and gender inequalities. Its magazine, Camerawork, offered a forum where the question of photography’s use as a tool serving people’s needs and interests could be further debated and tested out. It becomes evident across the book how this organisation became a reference point to all photographers and a central nexus for radical photographic practices in London and beyond.

The photographers involved in these collective organisations defended political stances at odds with conventional positions in the mainstream press and in conflict with parliamentary politics. They addressed deeply polemical issues which gripped British society, such as the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland, homelessness, the rise of the National Front as well as gender, race and class inequalities. The Exit Photography Group, connected to the Half Moon Photography Workshop through its member Paul Trevor, set out to document the divisive social inequalities across the UK in a decade characterised by increasing social strife, rising unemployment and mounting tensions. One core argument made by Stacey is that Exit photographers went against the grain of conventional photojournalistic practice in their choice not to credit their photographs individually and to maintain editorial control over the use of their images.

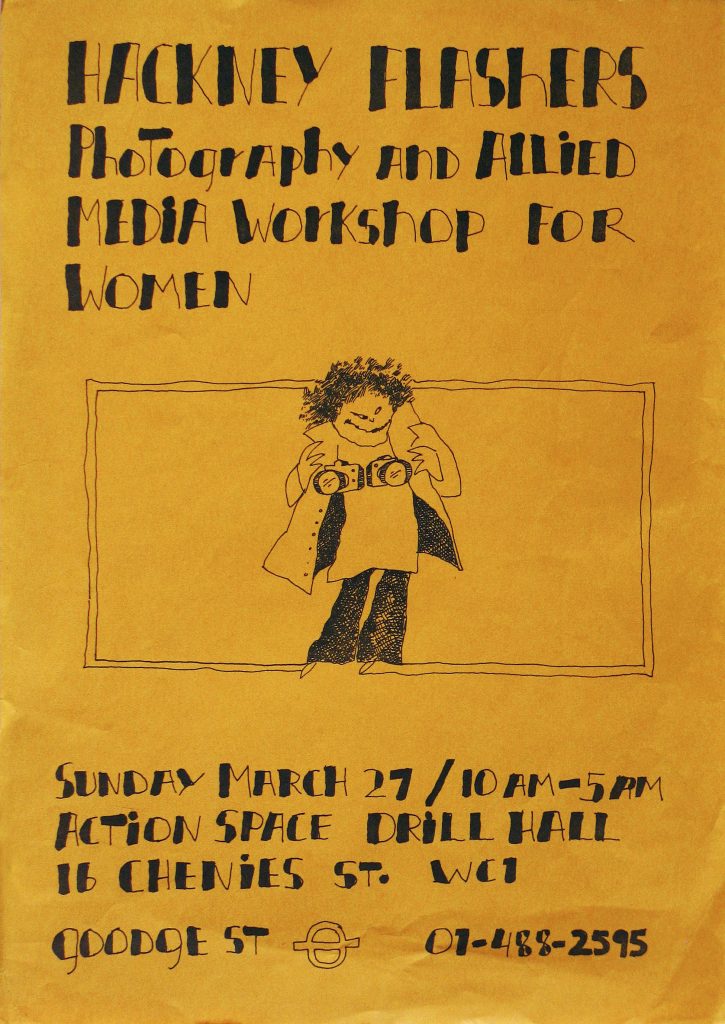

Image Credit: Workshop poster for the Hackney Flashers, illustration by Christine Roche.

Similar positions informed the values of the Hackney Flashers, an all-women feminist collective, which also had strong connections with the Half Moon Photography Workshop. Through their two shows (‘Women and Work’, 1975, and ‘Who’s Holding the Baby’, 1979) and the educational material that they conceived, the Hackney Flashers produced a collective vision, through photography, graphic design, montage and the use of statistics, which confronted the invisibilisation of women’s labour and exposed gender inequalities. Their work was concerned with amplifying the Women’s Liberation Movement’s demands regarding domestic work, reproductive rights, equal pay and childcare and with combatting the misrepresentation of women.

The ‘photography of protest’ documented by the author was also a photography in support of local communities’ protests. The community darkrooms set up at the Blackfriars Photography Project and the North Paddington Community Darkroom were resources providing residents with photographic equipment and guidance for their specific organisational needs. Placing cameras in the hands of people, photographers Paul Carter and Philip Wolmuth created the conditions for the exploration of alternative uses of photography by the people, for the people. Such photographic practices belonged to a wider counter-cultural scene rooted in values of cooperation, autonomy and grassroots activism.

The merits of the book lie in Stacey’s capacity to synthesise and contextualise the many different political, ideological and material stakes surrounding the emergence of a politically radical current in British photography in the 1970s. These encompass the deconstruction and remodelling of social documentary photography and its legacies, the creation of alternative production and circulation networks, the creation and sustaining of bonds with local communities as well as the implementation of inclusive, non-hierarchical and empowering principles in working practices and aims, defending accessibility to the medium as a democratic mode of expression.

Photography of Protest and Community appears in the context of active research on these subjects, produced by scholars, archivists, curators and photographers who all contribute to making the writing of this history a plural and collective enterprise. It may be regretted that the author only acknowledges this contemporary research in the final pages of the volume, at a time when the conversation on the legacies of this radical visual culture appears as vibrant and dynamic as ever.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Thank you to Lund Humphries and to all the photographers whose work is included in this review for allowing the use of their photographs. Permission to reproduce these photographs should be sought from the copyright holders.