Will social media replace face-to-face interaction in higher education?

This blog post is one of a series for the student engagement project LSE2020. It is written by Emma Wilson, Graduate Intern for LTI. You can find her on Twitter (@MindfulEm).

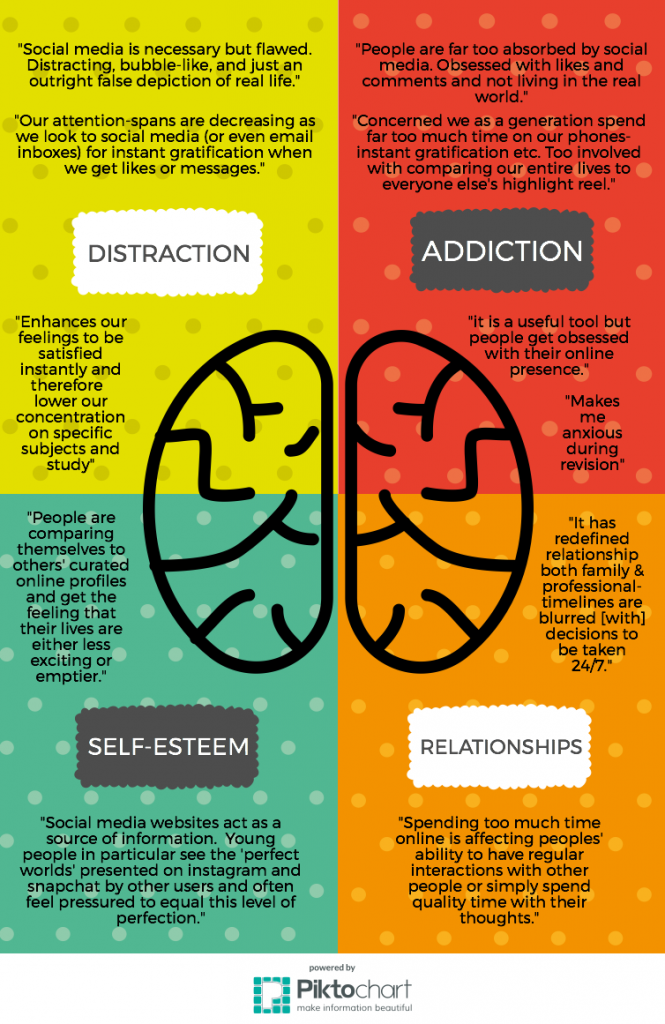

The online world is changing the way we receive, perceive and process information. We are living in a digital age of 24/7 connectivity and this undoubtedly has an impact on today’s teaching and learning experience in higher education. As discussed in our previous blog, students have spoken of the impact social media might have on our emotional wellbeing but what place do they think it should have in the classroom?

Whilst electronic forms of communication are an ever-increasing feature in the workplace, one must not forget or undervalue the importance of interpersonal skills. But what are the expectations of students in the way that classes are delivered? Do they see a decreasing importance in the traditional ways of learning such as office hours, study groups and seminars? Would they prefer to see a shift towards distance learning, Skype meetings and debates over social media?

With this in mind, it is important to consider the following:

Is social media eroding the need for face-to-face communication at university?

In addressing this question, our enquiry can be divided into two:

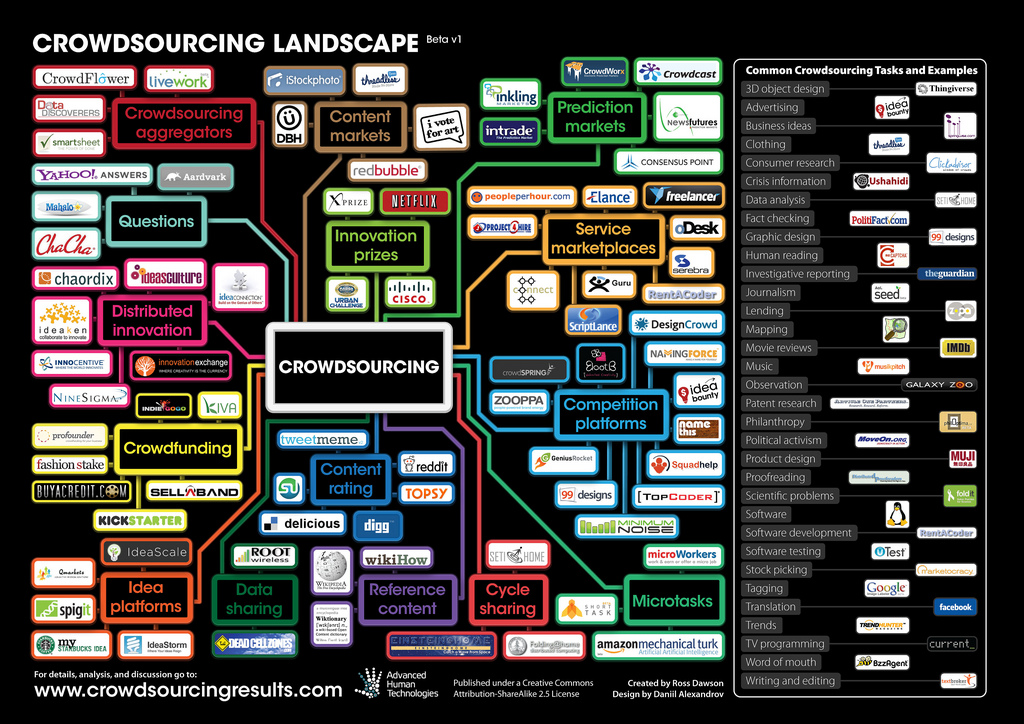

- How are students using social media, and are they expressing themselves online?

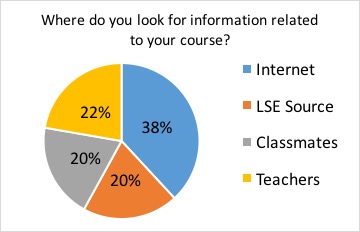

- When asked more specifically about seeking information relating to their course, which resources do they most value?

A key principle of LSE 2020 is its emphasis on an individual’s voice and their story. Analysis of student comments has enabled us to draw some interesting interpretations based on the data.

Based on the findings of 352 students who responded to our online survey, 41% of students told us they rarely express their opinion on social media. Students are active users of social networking sites such as Facebook and Instagram, and one in three students have a Twitter account. Is it therefore possible that students are passive users of social media, whereby they use social media to take in information, rather than create original content that is then shared within their local and wider networks? Or perhaps they actually are active users of social media but it has become a way of life and they don’t realise this would be defined as expressing oneself..?

Scroll through the comments below to read what students have told us…

Having considered the idea that students are cautious about sharing their opinions on a public social networking platform, there are three further questions to consider:

- If a private, LSE-managed forum similar to Facebook or Twitter could be developed, would students feel more confident in sharing their opinion in a safer environment? Or;

- Would students prefer to avoid social media altogether and use ‘real-life’ platforms such as interactive debate in the classroom?

- If students are keen to see social media greater incorporated into their learning, do they have any suggestions on how this could be best achieved?

*NB. LSE Source includes: Library resources, Moodle, lecture recordings, and other facilities managed by LSE on and off campus.

*NB. LSE Source includes: Library resources, Moodle, lecture recordings, and other facilities managed by LSE on and off campus.

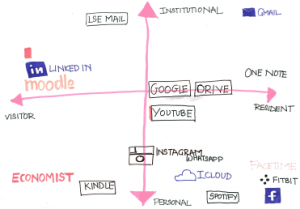

Despite constituting 38% of responses, 62% of students cited LSE-related sources when asked about where they access information relating to their course. Whilst, realistically, 100% of students will use the internet at some point for matters relating to their course, this data is interesting because it represents those answers that students first considered. Our data has also found that students attach some caution to searching for information online due to issues of reliability. It has also been found that students are comfortable searching the internet for quick reference (such as an unknown term during a lecture, for example), but that they would prefer to speak with their teachers or peers if they have a more complex query.

Finally, students have given some suggestions about how social media could enhance but not replace traditional methods of teaching. A selection of ideas can be found below:

“Encourage lecturers to set up module-specific Facebook pages/groups and have weekly/fortnightly Q&A sessions”

“Creating communication groups for each class either through Moodle or a separate messenger – not just a forum for the entire module group. Therefore, we can continue class discussions with the teacher & classmates after classes.”

“Blog discussions (for students) on specific parts of modules on Moodle- replica or extension of in-class discussions”

“Live questions from audience shown up on screen during bigger lectures so everyone can read them and submit them to the professor live.”

“Live stream lectures”

“More interactive polls/questions in lectures and classes”

“Maybe a social media where, a Facebook for LSE where you can turn files that would be like helpful to group, to share information. We use that now as a Facebook group for the whole generation of my classmates and every time that we want to share a book we have to put the link and make the link bespoke so in terms of sharing information or files, it could be like easier.”

“Skype meetings as part of an academic’s office hours, whether delivered individually or as a group. It would be great if the most frequently discussed topics of conversation could be added as a page on Moodle, kind of like an FAQ list.”

To conclude, social media is undoubtedly changing the manner in which students communicate and collect information in their personal, professional and academic lives. It is a way to connect but they have made it clear that social media should not replace face-to-face contact altogether. From live stream lectures to Q&A sessions on Facebook, students are citing opportunities to enhance what is already taking place in the classroom. Rather than fear the world of social media, there is potential to supplement and extend the teaching which is already deeply valued by students.