by Pejman Abdolmohammadi

After weeks of nuclear negotiations, not reaching an agreement would be particularly painful for both the Iranian government, led by the Rouhani-Zarif axis on one side, and the Obama administration on the other. Whether a deal is signed by the 10th of July or later, it will most likely only be a formal arrangement. I say ‘formal’ because, in my opinion and based on the current situation, the possibility of reaching an agreement that will definitively solve the Iranian nuclear issue doesn’t exist. In the current climate, signing a deal would represent, above all, a strategic political choice rather than a historical compromise between Tehran and Washington. In fact, contrary to what many analysts and lobbyists have been stating in the last two years, this would only represent a short term achievement. Such a significant and symbolic success would be a victory for both, American and Iranian, presidents. President Obama’s legacy would be solidified and Rouhani’s political position and legitimacy in Iran would benefit. An agreement would help paint Rouhani as a ‘saviour’, a president who brought some relief from economic pressures caused by sanctions and re-opened the Iranian economy to international trade.

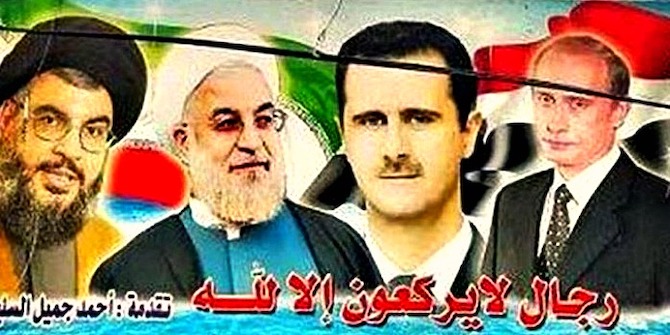

Despite this, the effects of a nuclear deal should not be overestimated as it’s worth noting that even if one is reached, by itself, it will not structurally change the current regional balance of power. The Islamic Republic of Iran is both a strategic and geopolitical ally of China and Russia, Washington’s main competitors, and it is not interested in becoming an ally of the West. Rouhani’s government was assigned the difficult task of dealing with the nuclear issue because he is expected to reach a pragmatic goal: to obtain sanctions relief and to diminish the economic pressures within the country. In addition, by signing a deal with Washington, the Islamic Republic aims to gain more international legitimacy, thus hoping to avoid any possible demand for regime-change in the next 15 years. The regime is now facing important domestic generational change, which might alter its political future. In Iran, of its 75 million people, almost 50 million are under 35 years-old and a significant proportion of this generation is critical or even opposed to the current political system. Therefore, beyond economic and security concerns, Tehran is vigilantly trying to control its potential domestic opposition, composed by the more progressive and secular parts of the youth and women. Thus, reaching a deal would not only offer relief from economic pressures by opening Iran to international trade and business, it would also likely strengthen the political system, ensuring the political survival of the current Islamic Republic’s model.

From an international point of view, Obama’s policy towards Tehran has also been based on pragmatism. This became evident after the ‘Green Movement’ of 2009 and the US’ lack of support for Iranian anti-governmental protests. Obama’s opening to Rouhani’s government in the past two years and the new, even if limited, relations between Tehran and Washington, clearly confirm this. The President aims to create a new balance of power in the Middle East, where Tehran would play a more prominent role and thus diminish Saudi Arabia’s influence.

This policy could be reasonable; with China and Russia rising as global powers and wanting to increase their economic and political influence in the Middle East, a new Western-friendly Iran, would certainly be important. Nevertheless, this geopolitical scenario does not consider the following matter: will Iran, under the Islamic Republic system, be structurally and ideologically capable of becoming an effective partner of the West?

My answer would be no: on the economic, military, security and political fronts, the Islamic Republic of Iran is much more interested in maintaining the status quo and avoiding any major changes to its current global alliance with Russia and China. Tehran still considers the US and the other Western states as a potential threat to its own security and stability. Therefore, the Iranian approach towards its Western counterpart, particularly during these nuclear talks, is driven by short term pragmatism.

If a deal is reached, to use a football metaphor, this first long match would end in a tie. However, there will be a return match, which will probably not be played by the same people. On the American front, it is not yet clear whether, in the post-Obama period, the Republicans or Democrats will take power next and what their stance will be. While, on the Iranian side, I predict that the Islamic Republic’s system, being a peculiar hybrid regime, will adopt a new strategy, likely more conservative and closer to the predominant group of the Pasdaran, that might weaken Rouhani’s government, depriving it of its current diplomatic team.

Dr Pejman Abdolmohammadi is Visiting Fellow at the LSE Middle East Centre. He is also Lecturer of Political Science and Middle Eastern Studies at John Cabot University in Rome. His research and teaching activities focus on the politics and history of modern Iran, the intellectual history of Iran, geopolitics of the Persian Gulf, and international relations of the Middle East.