by Madawi Al-Rasheed

J. E. Peterson’s edited volume, ‘The Emergence of the Gulf States’, is a welcome addition to historical knowledge about the Gulf and should appeal to students of the Gulf and those who are familiar with the region but need specialist knowledge to narrate the modern history, writes Madawi Al-Rasheed.

As Gulf states assumed great importance for their oil, strategic location and more recently regional interventions, this edited volume is timely. Its focus on the modern history of the six GCC countries and the foundation of their states provides great historical background to understand the contemporary era and its multiple challenges: from the fragmentation and failure of Arab national states, the rise of separatist movements, rivalry with Iran, terrorism, the economic crises and many other urgent problems.

The emergence of the six Gulf states, known as GCC countries – Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, UAE and Oman – is subject to controversial debate among historians. At first glance, one may argue that beyond nineteenth century British imperial designs and twentieth century oil, there is little historical common ground between Kuwait and the interior of Arabia for example, or between the first Wahhabi state and the Omani sultanates of bygone eras. Not to mention how Yemen is often excluded from this regional history. Oman and Yemen may indeed have more in common than Oman and Saudi Arabia. Yet, for political, economic and security reasons, since the 1980s knowledge about the Arabian Peninsula is segmented. In it, the GCC is constructed as a separate regional enclave for historical and comparative economic and political studies, leaving aside the southern corner of the Arabian Peninsula and the northern territories of Jordan and beyond.

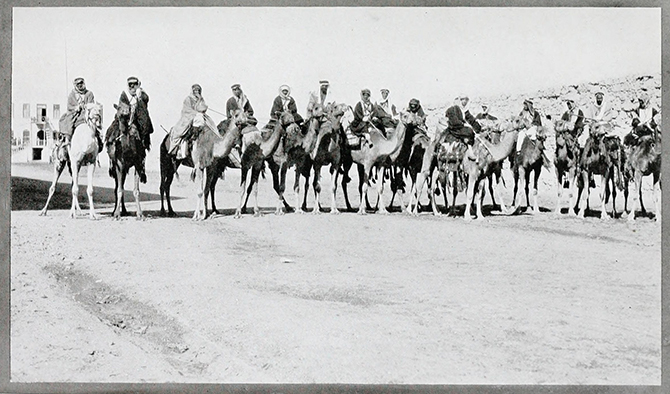

However, beyond their different political outlook, Gulf states share so much in common, especially at the level of tribal networks, rulers’ genealogies and cultural background, which makes them a regional microcosm worth considering for a comparative academic study like the one under review. Moreover, their historical transnational links that spread across the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean spanning Africa and Asia are also one of the distinctive common historical feature of this microcosm. Their post-WWII oil economies and the subsequent flux of migrants to the region are common economic features that separate the GCC from the rest of the Arab world, especially the Mediterranean sea, with countries in North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean shores opening up to southern Europe.

J.E. Peterson’s edited volume The Emergence of the Gulf States is no exception from the general pattern of Western historiography of the Gulf. Its eleven case studies exclude Yemen, focusing solely on the six GCC states. Consequently, it casts a quasi-coherent regional modern historical framework on six states, some steeped in history while others are as recent as 1971. The book covers the modern history from the eighteenth century to 1971, the year that saw the establishment of the most recent states, namely the UAE and Qatar.

The introduction is partly a reflection on Gulf historiography in general, and partly a summary of the contributors’ chapters, written by well-established scholars of Middle Eastern Studies, historians, linguists, political scientists and anthropologists.

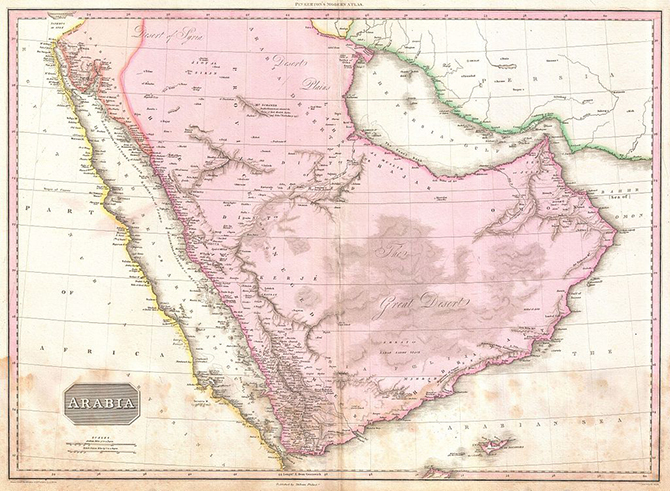

Peterson claims that ‘much of our understanding of the Gulf in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and even the eighteenth centuries derives from the accounts of European travellers, because most of the population was not literate’ (p. 3). According to Peterson, from the Portugese Alfonso de Albuquerque to British H. St. John B. Philby, the regional history of the Gulf was mapped by European travellers, merchants, imperial agents, colonial officers, spies and oil men turned scholars, and vice versa.

The list of European sources is long indeed, but the introduction does not evaluate this vast literature, nor does it explain how it can be useful in writing the history of the Gulf. Given that most historical studies now include reflections on the primary sources and their contribution to constructing and imagining the past, it is rather disappointing that such methodological necessity is completely overlooked by both the editor and the contributors. Such omission diminishes the scholarly value of the book, especially among novices who want to embark on a career as specialists in the modern history of the region.

The editor naturally privileges British archives, obviously the first historical collection that became the dominant primary source at least for the nineteenth century. Yet, many young scholars nowadays are shocked by the restrictions that the British government still imposes on some files in these archives. It is reported that some archival sources are under 90-year restrictions, a telling censorship that demonstrates the degree to which Britain had been and still is entrenched in so many intrigues in the Gulf whose ramifications are still relevant today.

While British archives are detailed and easily accessible given the historical imperial interest in the Gulf from both London and Bombay, one must acknowledge that other European powers had their own designs and intrigues in the Gulf, even when the region fully fell into the British sphere of interest. In fact, Peterson highlights this fact in his excellent chapter. France and its archival sources should be included in any methodological note on Gulf sources, especially in the nineteenth century.

Moreover, with pilgrimage increasingly becoming more important in its magnitude and number of pilgrims visiting Mecca and Madina always growing since the nineteenth century, one must remember that pilgrims beyond Indian Muslims, mainly from South East Asia became an important cohort, thanks to steam ships. Their journey certainly prompted the Dutch to start their own contribution to recording the history of the Arabian Peninsula from Jeddah. Such archives are not easily accessible because of language barriers, but they should at least get a mention. Finally, the Ottoman sources on the history of the Arabian Peninsula in general and the Gulf in particular remain partially consulted with few exceptions, for example the work of Saudi historian Muhammad Zulfa on the southern western region of Arabia (Asir) and the monographs of Ottomanists in general.

The introduction briefly and quickly acknowledges the contribution of local GCC historians who emerged since the 1970s but fails to critically assess the value of their scholarly work. Peterson points attention to those new local historians who received Western education in the second half of the twentieth century, thanks to government scholarships to study abroad with a view to write their own states and nations. The first cohort of Western-trained local historians played an important role in framing the Gulf especially when the new states wanted to fix their history, heritage and the past in general in ways that highlight certain themes, for example foreign interventions, both continuity and discontinuities with the past, the story of pearls, oil and merchants, and most importantly the ‘ancient’ leadership. This last concern often translates into histories of local chieftains, amirs and sultans. Among the new historians, only Emerati Dr Shaikh Sultan ibn Muhammad al-Qasimi is mentioned in the introduction, perhaps in appreciation and acknowledgement of the funding source that sponsored this book project.

This methodological shortcoming is remedied in the bibliographic essays that are attached to each chapter. One such bibliographical note follows Peterson’s chapter on the entry of the Gulf in the age of empire from the sixteenth century onward. Peterson decentres oil as the main trigger for the entry of the Gulf into the international order, and shows how long historical trade routes and imperial interests competed over the Gulf, with multiple European powers trying to control trade routes that connect Europe itself to far flung territories in Asia and beyond. He explores the Anglo–French rivalry in which the Gulf became a ‘putative and potential battlefield’, so obvious in Oman at the turn of the twentieth century and the German thrust in the region that manifested itself around the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway. However, such rivalries finally gave way to the Gulf becoming so important to the US in the post-WWII era and the advent of the Cold War. He concludes this important chapter by pointing attention to the current rivalry between GCC countries themselves, such as the Saudi–Emerati axis against Qatar that erupted several times since the 1990s. The last inter-GCC conflict crystalised around Oman leaning towards greater cooperation with Iran, rather than following the Saudi line of outright rejection or compromise. Recently, the Saudi–Qatari relation soured and erupted into outright hostility over alleged Qatari leaks and the latter’s promotion of Islamists around the Arab region. While the six states struggle to reach consensus within the umbrella organisation of the GCC, they occasionally compete and collide to the detriment of real unification. Their modern history offers real insight into how these small states had dealt and continue to deal with two ‘Big Brothers’, mainly Iran and Saudi Arabia.

One of the most interesting and well-documented chapters in the book deals with religion and religious movements (1700–1971). Michael Crawford is a well-known historian, who spent his career working behind the scenes for the British government rather than in academic institutions. His historical insights are profound and illuminating. This chapter confirms his well-grounded knowledge and understanding of the religious diversity in Arabia prior to the establishment of all GCC states. His main focus is on how religion and religious movements, with the exception of for example Wahhabiyya, had been overlooked in the study of the region. He argues that over the period 1700–1971 Sunnism and Shi’ism were moving, however, uncertainly and unevenly, on contrasting trajectories with regard to the relationship between political power and religious authority. In Ottoman times, there was an attempt to maintain close relationship with Sunnis of diverse outlook from Sufis to Asharis. But Wahhabiyya, the nineteenth century revivalist movement in central Arabia, initially uprooted religious hierarchies and subverted the special authority of clerics, especially those of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, Wahhabi clerics practised takfir (excommunication) on the Ottoman state and its Sufi tariqas.

Crawford explains the recent fragmentation of the Wahhabi tradition since the 1990s and the rise of both quietist conservative elements and Jihadi violence from its own rank and file. The Gulf countries seem to have initially shielded themselves from this historical pattern until recently, when they too became engulfed – but not to the same degree as Saudi Arabia – by the radical interpretations of the Wahhabi tradition.

In contrast, in Shi’ism, Crawford argues, there was a doctrinal and institutional divide between clerical and political authority that later on culminated in the Iranian model of wilayat al faqih (rule of Jurist), a recent development in Shi’i theology associated with Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini.

The Gulf and the Indian ocean are discussed in a very interesting chapter that focuses on ancient Gulf activities in the wider maritime region. Bishara and Risso trace these maritime connections through an analysis of monsoons and trade. In this vast maritime network, Bombay played an important role, becoming a hub of Gulf activities with Indians and others participating in making long lasting connections that only became even stronger in the oil era with the flux of Asian immigrants to the Gulf.

A concluding chapter by well-known Frauke Heard-Bey tackles the process of state-formation. It maps the different trajectory of each country: the Kuwaiti city state, the Qatari accidental state, the tribal Trucial state, two communities, one Bahraini state, the Imamate and Muscat state, and the politico-religious empire of Saudi Arabia. The chapter celebrates the ‘constitutionalism’ of these states that is perhaps overstated.

While it is not possible to discuss all chapters in this review, the volume is a welcome addition to historical knowledge about the Gulf and should appeal to students of the Gulf and those who are familiar with the region but need specialist knowledge to narrate the modern history. However, its tone is somehow congratulatory and could have benefitted from serious critical evaluation and revisionist historical approaches to the region. For example, the recent interest in the history of commodities that travelled from the Gulf to other parts of the world or came to the Gulf on its way to Europe remain understudied. The Gulf–Malabari coast connection and trade in gold is now the subject of several interesting studies. In addition, the transport of Arabian horses as far as Australia under the auspices of the British empire must have had an impact on both the coastal states and the interior of Arabia, especially as a trigger for generating surplus that laid the foundation for political centralisation. Another aspect of this modern history relates to the migration of Arabian tribes to the northern regions, mainly Syria, Iraq and Egypt, where many found employment digging the Suez canal in the nineteenth century. How such connections transformed the region and shaped the history of state-formation is still an ongoing research interest that the book should have at least mentioned.

Madawi Al-Rasheed is Visiting Professor at the LSE Middle East Centre. In January 2017, she returned to the MEC from a sabbatical year at the Middle East Institute, the National University of Singapore. Previously she was Research Fellow at the Open Society Foundation. Since joining the MEC, Madawi has been conducting research on mutations among Saudi Islamists after the 2011 Arab Uprisings. She tweets at @MadawiDr.