by Lisa Gormley

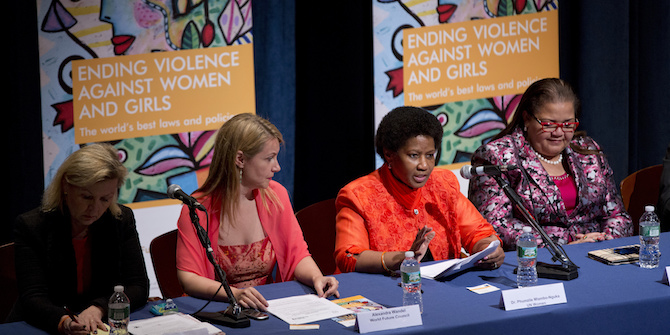

UN Women/Ryan Brown

Over the past 25 years, international and regional human rights processes – political declarations, treaties, and jurisprudence – have elaborated the various principles of international human rights law which need to be respected in order to ensure women’s access to justice for gender-based violence.

The fact that many legal issues have been resolved at the level of international human rights law is due, on one hand, to a succession of regional treaties, in the Americas, Africa and most recently Europe, specifically on violence against women or on women’s rights, and on the other hand, declarations on women’s rights from various political bodies of the United Nations, such as the Security Council and the General Assembly. In both strands of development, feminist lawyers and experts have intervened with their insights from the experiences of women on the ground, and their struggle to secure justice. Independent human rights experts appointed by UN bodies, especially successive Special Rapporteurs on violence against women, Special Rapporteurs on torture, and Special Rapporteurs on the independence of lawyers, have produced analyses and recommendations to improve justice systems for women and girls who are victims of violence.

Feminist lawyers have also developed jurisprudence, by bringing cases of violence against women through domestic legal systems, and, where they still have not received justice, they have brought these cases to international and regional human rights adjudication, for example, to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against women, and to the European, African, and Inter-American human rights courts. Each case is the story of a woman or girl and her struggle for justice, the story of the human rights violation that was inflicted on her through gender-based violence and the fruitless struggle to secure justice. Usually the facts supporting the application show a clear history of State failures to ensure effective protection from violence and missed opportunities to secure justice after the violence has been committed: and the submissions propose solutions and suggestions for improvements.

Women’s access to justice for gender-based violence is important because it consists of the intersection between three foundational human rights principles: the human right not to be subjected to torture or ill-treatment; the human right not to be subjected to discrimination on the grounds of gender: and the right to a remedy for violation of human rights. All of these are expressions of customary international law, that is, that they apply to all States irrespective of treaty obligations, and this constellation of legal obligations leads to very specific legal outcomes.

The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the UN General Assembly both issued landmark documents relating to women’s right to justice for gender-based violence in the early 1990s. These both emphasised that traditional attitudes are a cause of gender-based violence against women and therefore violate women’s human rights. They both also emphasise that states are legally responsible for the actions of non-state actors when they fail to take the appropriate steps to prevent, investigate and punish acts of violence against women.

Feminist legal advocacy was important throughout the 1990s and early 2000s to clarify the law relating to acts of violence against women committed by non-state actors, through jurisprudence in the Americas and Europe, and then subsequently the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, after the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women entered into force.

Jurisprudence particularly sheds light on the attitudes of prosecutors and the judiciary in failing to take account of women’s entitlement to protection of the law where violence takes place in families. In cases at the CEDAW Committee, the cases of A.T. v Hungary and Angela González Carreño v Spain, two cases relating to domestic violence committed by an abusive husband, the CEDAW Committee criticised social attitudes which become manifest in the judiciary, in its professional activities and legal judgments, when they discriminate against women and their children. These include attitudes which promote the right of fathers/husbands to privacy and property (A.T. v Hungary) and contact with their children (González Carreño v Spain) above the right to safety of women and children. Feminist activism and jurisprudence show that social attitudes towards violence against women which prioritise male entitlement are common across all regions of the world.

The most recent explanation of the content of women’s entitlement to access to justice is the CEDAW Committee General Recommendation 33 (2015) on women’s access to justice, which incorporates agreed concepts from the regional treaties and the regional and universal treaty law, specifically, the CEDAW cases. This General Recommendation relates to women’s access to justice for all forms of discrimination and failure to ensure equality with men – not just gender-based violence. But the reality is that access to justice for gender-based violence cannot take place in a vacuum from other forms of inequality, especially inequality in domestic laws and in practice in the family, in public life, including access to citizenship, inequality in laws and practice relating to freedom of movement and association, and inequality in law and in practice in the workplace.

Often these gender inequalities stop women from seeking justice. Other inequalities include the risk, if a woman seeks justice, of making her situation worse, particularly if reporting rape leads to the stigma related to being identified as a victim of sexual violence. Often the intersection between family and personal status law, and criminal law, particularly in seeking access to justice for domestic violence, means that a woman experiencing violence from a husband will not seek criminal justice or a divorce, because she knows that if she does this, she will lose access to her children. Lack of education and lack of economic means stop women from seeking assistance from lawyers.

One very significant issue that stops women seeking justice for gender-based violence is the use of alternative dispute resolution processes such as negotiation and reconciliation. These are contrary to the rule of law – in no other criminal issue are a victim and the perpetrator encouraged to reconcile. Indeed, this is an issue of stereotyping, contrary to Article 5 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, as this promotes an archaic viewpoint that what are in reality crimes of violence are interpersonal conflicts where both sides have to take steps to modify their behaviour. Often alternative dispute resolution processes prioritise community cohesion or family reputation and family unity above women’s right to justice for gender-based violence, and the CEDAW Committee has said that, under no circumstances should violence against women, including domestic violence, be referred to alternative dispute resolution (see paragraph 58(c) in CEDAW General Recommendation 33).

Where these social, cultural and contextual inequalities are dealt with, then the content of the law and administration of law for gender-based violence deals with bureaucratic technicalities which are fairly standard and reflect the need for equality at each and every stage of the justice process:

- that the components of access to justice include – justiciability, free and equal laws, availability of justice mechanisms, good quality of justice provision and accountability of justice systems. Independent and good quality judiciary, free of corruption, bias or stereotyping, providing timely and efficient remedies;

- that equality is enshrined in the law, whether criminal, family/personal status law, civil law, administrative or public law, so that women can freely seek justice on their own terms, without having to seek permission of anyone, and have the same access to legal processes, such as divorce, child custody etc. as men;

- a requirement for social services, such as hotlines, advice centres and provision of information so that women can be empowered to seek justice;

- the necessity of civil protection orders, measures to protect victims’ privacy;

- a requirement for specific definitions of crimes – especially relating to sexual violence – which protect women’s and girls’ physical and mental integrity and personal sexual autonomy, rather than moral order, or the entitlement of a man to sexual contact with his wife without her agreement;

- an end to impunity of perpetrators, to ensure effective deterrence, particularly in the cases of so-called ‘honour killing’ (the phenomenon often referred to as ‘crime of passion’ or ‘provocation’ in Europe and the Americas);

- gathering of data to ensure that women are able to access justice in equality with men.

In short, the international and regional human rights laws relating to access to justice for acts of gender-based violence against women are remarkably consistent and constitute a coherent whole. It is against this context that developing initiatives and practice around the Arab Charter on human rights should be seen.

Most recently, (UN Doc CEDAW/C/GC/35, 14 July 2017) the CEDAW Committee has published General Recommendation 35, updating its guidance from General Recommendation 19 on the content of women’s right not to be subjected to discrimination, in the form of gender-based violence. General Recommendation 35 reflects the 25 years of legal and policy experience, and confirms that gender-based violence has evolved into a principle of customary international law. This new General Recommendation reflects new developments in how gender-based violence is perpetrated – ‘a continuum of multiple, inter-related and recurring forms, in a range of settings, from private to public, including technology-mediated settings and in the contemporary globalized world it transcends national boundaries’ but also that ‘the ideology of men’s entitlement and privilege over women, social norms regarding masculinity, the need to assert male control or power, enforce gender roles, or prevent, discourage or punish what is considered to be unacceptable female behaviour’ persists. With this General Recommendation, we now have an even more detailed blueprint for change, in all regions and countries in the world.

Lisa Gormley served from 2000 to 2014 as a legal adviser at Amnesty International’s International Secretariat, mostly specialising in women’s rights in international law. Since leaving, she has been teaching the module on women’s human rights law on the LLM program at Essex University (2015 and 2016). She also wrote the Practitioners’ Guide on Women’s Access to Justice for Gender Based Violence (PDF) as a consultant for the International Commission of Jurists, published on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2016.

Lisa Gormley served from 2000 to 2014 as a legal adviser at Amnesty International’s International Secretariat, mostly specialising in women’s rights in international law. Since leaving, she has been teaching the module on women’s human rights law on the LLM program at Essex University (2015 and 2016). She also wrote the Practitioners’ Guide on Women’s Access to Justice for Gender Based Violence (PDF) as a consultant for the International Commission of Jurists, published on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2016.

In this series:

- Introduction by Courtney Freer

- A Survey of Knowledge of and Attitudes toward Article 153 among Kuwaiti Citizens by Justin Gengler

- Is Female Suffrage in the Gulf important? by Hatoon Al-Fassi

- Saudi Women: Navigating War and Market by Madawi Al-Rasheed

- Disciplinary Violence in Kuwait by Alanoud Alsharekh

- The Influence of Islamist Rhetoric on Women’s Rights by Courtney Freer

- Gender Equality in Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan by Zeynep Kaya

- Sexual Violence against Women during Displacement by Zeina Awad

- Assessing the Role of Security Forces on Women in Conflict Zones: Perspectives from International Law by Antonia Mulvey