by Toby Dodge

This article is part of a collection of tributes to the late Faleh A. Jabar.

The death of Faleh Abdul Jabar in Beirut, on 26 February 2018, has deprived the academic world of the leading intellectual working on Iraq. However, the contribution that Faleh made to Iraq over his lifetime was much more than purely intellectual, for he was a committed political activist as well as a sensitive and supportive mentor to generations of younger scholars, myself included. His commitment to broadening public understanding of Iraq was so deep that his final act, in spite of months of ill health, was to take part in a television interview about the long-term significance of Iraq’s elections.

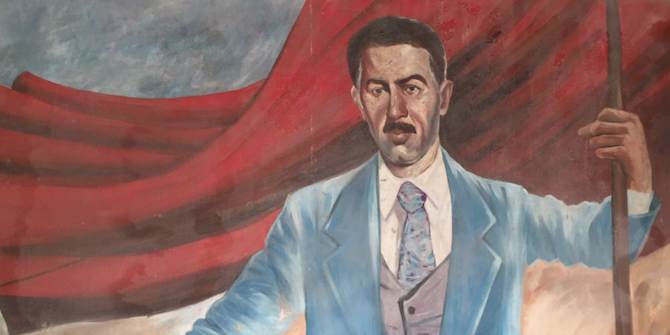

I first met Faleh in London at a workshop he organised, ‘Post-Marxism, and the Middle East’, in June 1995. This event and the subsequent edited volume that arose from it, can be seen as a point of departure for the rest of Faleh’s work on Iraq. Faleh, as a younger man, had been a deeply committed member of the Iraqi Communist Party who put his life in danger to fight for its partisans, not only to rid Iraq of the tyranny of Ba’athism but also to transform the country into a more progressive and egalitarian society. However, the workshop and book that it produced was focused on the ramifications of the collapse of the Soviet Union for leftist and progressive forces across the Middle East. As he argued the ‘end of existing socialism’ was not an unexpected cataclysm but the culmination of a long-running process, which had seen the modernist optimism of progressive forces in the Middle East crushed under the power of nationalist ruling elites:

… the orphans of the Gorbachev era had experienced successive defeats at the hands of the rising nationalists … The zeal, confidence and vitality of this generation had been eroded by years of persecution, and the vacuum they had left was frequently occupied by the rising new current of Islamic fundamentalism.[1]

Against this background, the intellectual trajectory of Faleh’s work can be seen as a reaction to those myriad defeats and an attempt to document and explain the forces that gave rise first to the violent authoritarianism of the Ba’ath in Iraq, but after their removal, to the rise of Islamism and the forces of sub-state sectarianism.

Faleh’s work on Ba’athist rule in Iraq is remarkable for two reasons. First, in spite of the horrors that the dictatorship of Ahmed Hassan al Bakr and then Saddam Hussein unleashed on the country, on Faleh’s party and on his own friends and family, his research and publications on them was carried out from within the rigorous discourse of a dispassionate social science. It certainly delivered damming judgments on their violence, corruption and the long-term damage they inflicted on Iraq. However, it never dissolved into partisan nor personalised language. Secondly, the reason this work is at the cutting edge of intellectual research is its combination of powerful insights from the Social Theory that Faleh was so familiar with but also the strength it drew from the comparative study of authoritarianism. Finally, it certainly brought home the long-term ramifications of Ba’athist policies but its power was also derived from the study of those who suffered the most, ordinary Iraqis. The power of these arguments can be found across Faleh’s work but, for me, especially in two papers. The first is Faleh’s research on how the youth of Iraq were transformed by the 1980 to 1988 Iran-Iraq war, the 1990 invasion of Kuwait and then the brutal transformation caused by over a decade of harsh sanctions.[2] At the centre of this paper is a sympathetic examination of the consequences for Iraq’s youth of this brutal socio-economic transformation. The second paper, which shows the exacting social scientific logic at the heart of Faleh’s work and the powerful insights that this delivered, is a publication on Iraq’s tribes.[3] Faleh was well aware of the Orientalist dangers of reifying the ‘tribe’ as a timeless essence of an unchanging Middle East. Instead, he shows the Iraqi tribes as being in a constant process of change and transformation. This process runs from the period when Iraq was integrated into and hence transformed by the global economy in the later period of Ottoman rule, right up to what Ba’athist policy did to tribes and shaikhs under sanctions. The result is a superb piece of applied social scientific research. It is certainly rich in empirical detail but also develops a nuanced argument about how social formations are transformed by modernity and state policy. The result, in Iraq in the 1990s, was that the ‘chieftains made in Taiwan’ were ‘second-hand copies of lower value’, individuals claiming the socio-cultural mantle of tribal shaikhs were, in reality, shoddy malfunctioning copies.

The third focus of Faleh’s work was the varying influence and organisational coherence of socio-religious formations in Iraq. Faleh’s chose as his case study the rise of Shi’ite Islamist militancy. The work was started as a PhD under the supervision of Sami Zubaida at Birkbeck College, University of London and completed with the publication of the book, The Shi’ite Movement in Iraq in 2003.[4] It is in this book that Faleh’s intellectual method is shown to its greatest effect. The influence of Max Weber and Hegel as well as Marx is clear. This is married with years of detailed empirical research. The result is the definitive work on Shi’a political activism in Iraq. Faleh deploys Weber’s notion of Gemeinschaften to make the powerful point that political mobilisation in the name of Shi’a religiosity was a modern form of social organisation and hence in constant transformation. He marries this powerful analytical insight with a study of state influence, both after the revolution of 1958 and the coup d’état of 1968. This study starts with an examination of the defensive reaction to the secularising trends unleashed after 1958 and finishes with the first detailed examination of the social basis of the Sadrist movement after 2003. Overall, this book will continue to be read for the powerful insights it gives into religious mobilisation, state power and social transformation.

The final focus of Faleh’s work was research and publications he carried out after regime change in 2003, trying to explain the civil war that swept the country under US occupation but also the rise in political mobilisation and violence justified in the name of religious and ethnic division. With the removal of the Ba’ath, Iraqi politics appeared to move with great and sometimes bewildering speed. It is here, once again, that Faleh’s own combination of social scientific analysis and detailed empirical research allowed him to move away from rash judgment and situate Iraq’s post-2003 transformation in its historical and comparative perspective. The result was a series of publications that certainly explained Iraq to the wider world but also avoided analytical short-cuts or clichés and hence whose conclusions have stood the test of time.[5]

Beyond his work as an academic, Faleh’s legacy is also as an intellectual mentor and teacher as well as a political activist. For someone with such an extended knowledge of both social theory and Iraqi history, he wore his learning lightly, interacting with younger scholars with patience and humility. When I was a young PhD student, Faleh listened with interest to one of my first papers on Iraq, given to the Middle East Studies Group run by Sami Zubaida. He interacted with its central argument in detail, offering insights and suggestion. He then gave me one of my first publications in a book he was editing but not without sending me back into the archives to ensure the historical sources I had deployed to make my argument were accurate. This sustained commitment to nurturing young scholars but also making sure they were trained in an exacting and sustainable way was placed at the centre of his research centre, the Iraq Institute for Strategic Studies, when it was opened in Beirut. Numerous young Iraqis have been rigorously trained there as social science researchers, sent back to Iraq to carry out analysis, with their conclusions then published by the institute. This reflected not only Faleh’s skills and commitment as an intellectual mentor but his conviction that Iraq desperately needed well trained social scientists to study the country and inform its population and their leaders about what was happening to them, why this was occurring and how this would impact on their collective futures.

Beyond his commitment to being an academic and to training a new generation of Iraqi researchers, Faleh remained a deeply committed political activist. His bravery and honesty in the face of the violence and corruption that engulfed Iraq after 2003, stood out as an example for both academics and activists. Although he had moved away from the Iraqi Communist Party, he remained deeply engaged in Iraqi politics, championing the rule of law, probity and transparency that he thought could only be delivered through a sustained and fully functioning liberal democracy. In March 2016, I was lucky enough to visit Baghdad with Faleh, where we met with the leading members of Iraq’s ruling elite. This culminated with an extended audience with Nuri al-Maliki at his home, surrounded by a large entourage of advisers and bodyguards. As the meeting ended, Faleh, who refused to be overawed, engaged the ex-prime minister in a lively discussion, taking him to task for the damage his policies had done to Iraq. This, to my mind, shows Faleh at his best, an Iraqi intellectual of huge repute, taking to task one of its leading politicians, honestly and analytically critiquing his record without fear nor favour.

The last time I met Faleh was in early in 2018, on a bright sunny January morning at his research centre in Beirut. Although he was clearly unwell, he soon became energised as we discussed the future of Iraq, its politics and society. He was full of ideas about how the Middle East Centre at the London School of Economics could collaborate with the Iraq Institute for Strategic Studies to carry out research on the socio-political dynamics shaping Iraq’s future. This is how I will remember Faleh, in his institute, planning research projects on Iraq, committed to explaining the country’s past, present and future trajectories, while laying the groundwork for the rigorous academic study of the country that he loved.

[1] Faleh A. Jabar, ‘Introduction’, in Faleh A. Jabar (ed), Post-Marxism, and the Middle East, (London: Saqi Books, 1997), p. 10.

[2] Faleh A. Jabar, ‘The war generation in Iraq: a case of failed etatist nationalism’, in Lawrence G. Potter and Gary G. Sick, Iran, Iraq, and the Legacies of War, (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004),

[3] Faleh A. Jabar, ‘Sheikhs and Ideologues: Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Tribes under Patrimonial Totalitarianism in Iraq, 1968-1998’, in Faleh A. Jabar and Hosham Dawod (eds), Tribes and Power: Nationalism and Ethnicity in the Middle East, (London: Saqi Books, 2003), pp. 69–101.

[4] Faleh A. Jabar, ‘The Social Origins and Ideology of the Shi’i Islamist Movements in Iraq; 1958-1990’, PhD Birkbeck College, 1999 and The Shi’ite Movement in Iraq, (London: Saqi Books, 2003).

[5] See, for example, Faleh A. Jabar, Renad Mansour and Abir Khaddaj, ‘Maliki and the Rest: A Crisis within a Crisis’, Iraqi Institute for Strategic Studies Iraq Crisis Report – 2012, http://iraqstudies.com/Maliki%20and%20the%20Rest%20-%20A%20Crisis%20within%20a%20Crisis.pdf