This article is by Bonny Astor on a talk by Stephen Bush (@stephenkb) at the Polis Summer School

“The age of privacy is over and the age of censoriousness is diminishing”

Stephen Bush – editor of the Staggers– is optimistic about the twitter mob’s declining political influence and predicts a more relaxed future in which people care less about politicians’ minor online blunders and teenage mistakes.

Political journalism is different when it’s online.

Political journalism is different when it’s online.

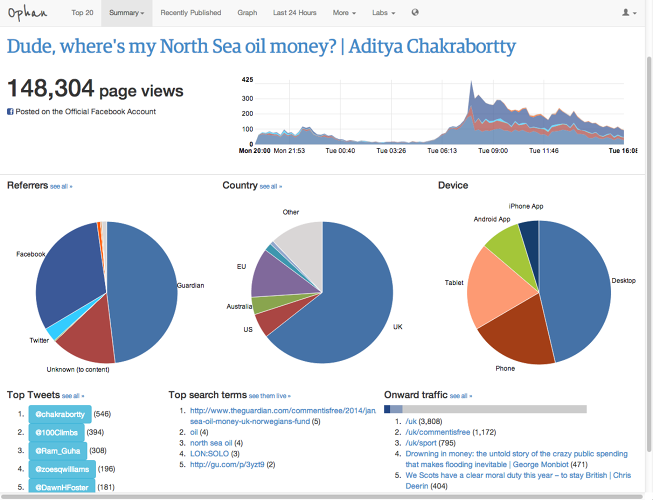

Bush began by explaining that the online version of the New Statesman is basically the same as the print version, but with one key addition. The online version provides rolling updates on political stories and figures, or as Bush described it, “MacDonald’s for political news junkies”. This seemingly niche function is significant because it fuels the fast-paced online political discussion made possible by the Internet and social media.

A major component of online political discourse is the critique of prominent individuals for both their professional and personal presence. The ‘political news junkies’ who read Bush’s blog are among the first people to notice politicians’ poorly judged comments and mistakes. Armed with Twitter, Facebook, and a plethora of other social media platforms, these individuals – often anonymous and hidden behind laptops, tablets, and smartphones – have the power to create influential online ‘chatter’.

‘Twitter-storms’ and the like can represent formidable threats to politicians’ career longevity and are not to be taken lightly. Just last year, Labour MP Emily Thornberry sparked a furious and ferocious backlash by posting an objectively innocuous photo on twitter. The photo was of a typical working class home adorned with flags bearing the St Georges’ cross and West Ham Football Club’s crest, and with a white van parked in the foreground. Thornberry’s tweet, which read “image from #Rochester”, was instantaneously reframed with the addition of a single word: ‘Snob’, and taken as a stereotypical and malicious jibe at the working classes. The pace and severity of the ensuing ‘twitter-storm’ motivated a snap decision by Labour party leader Ed Miliband to sack Thornberry later the very same day.

The Thornberry case was extreme, but media scrutiny and criticism of politicians’ behavior is common. In 2008, David Cameron was labelled a ‘Toff’ and derided accordingly when a group photo of the 1992 Bullingdon Club surfaced in the news and Cameron was identified alongside Mayor of London Boris Johnson and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne. In the run up to the 2015 general election, 20-year-old Scottish National Party (SNP) MP Mhairi Black was criticized when the media found her ‘not-safe-for-work’ teenage tweets relating to inebriation, football fandom, and a distain for nuns and mathematics – the latter put simply: “maths is shite”.

Although Black and Cameron would probably have rather kept their pasts private, neither suffered politically as a result of the attention. Both scandals proved to be short-lived and ultimately inconsequential. Black became the UK’s youngest MP since 1667 and Cameron won the 2015 general election with an outright majority – the first Conservative leader to do so in 23 years.

Having observed such outcomes, Bush thinks that people are beginning to “get over” the human failings of their political leaders. Budding young politicians – and young people in general – will be increasingly able to relax social media self-censorship because realistically, “If we screened everyone who said things like, ‘I was too stoned to do my coursework,’ on Facebook, we wouldn’t hire anyone”.

So if teenage misdemeanors and even mildly un-PC statements are becoming less important, what will future twitter-storms revolve around? Bush’s analysis of one particularly ridiculous and recent PR fiasco – the ‘Ed Stone’ – indicates that with or without social media, politicians are endlessly capable of providing the public and the media with ammunition.

“Everything about it was bad”

The ‘Ed Stone’, a 2.6-meter tall slab of limestone engraved with Ed Miliband’s election promises, featured prominently in the media during Britain’s recent general election. The election symbol became the subject of fierce ridicule and, in the aftermath of Labour’s defeat, a nationwide search – the stone mysteriously disappeared after 7 May and was subsequently reported to be under lock and key in a South London garage. Although social media played a crucial role in the ‘Ed Stone’ debacle – serving to exponentially amplify the mistake – Bush explained that the root of the problem was a gross PR miscalculation rather than a new media phenomenon. The moral of the story according to Bush was not regarding social media practices, but rather: “Don’t be bad at politics”.

@BonnyAstor

For updates on the Polis Summer School follow #PolisSS

Stephen Bush @ Polis Summer School 2015 from Polis Video on Vimeo.