Labour re-entered the policy debate in the area of childcare with the eye-catching announcement that if elected in 2015 they would extend free childcare provision from 15 to 25 hours for all 3 and 4 year olds with working parents. But is this the right way to spend precious government resources in an age of austerity? Work done by Kitty Stewart and colleagues leads them to think that yes it is – for three main reasons: it would sharply reduce the cost of childcare for parents, it would break down the barrier that currently exists between part-time and full-time settings (also facilitating employment), and it would reduce the social segregation which currently seems to be on the rise in early years settings.

Labour re-entered the policy debate in the area of childcare with the eye-catching announcement that if elected in 2015 they would extend free childcare provision from 15 to 25 hours for all 3 and 4 year olds with working parents. But is this the right way to spend precious government resources in an age of austerity? Work done by Kitty Stewart and colleagues leads them to think that yes it is – for three main reasons: it would sharply reduce the cost of childcare for parents, it would break down the barrier that currently exists between part-time and full-time settings (also facilitating employment), and it would reduce the social segregation which currently seems to be on the rise in early years settings.

It is hard to remember now that early childhood wasn’t always a UK policy priority. Until the mid-1990s, once a baby was safely born, they largely disappeared into the periphery of the state’s vision until they turned up at school nearly five years later.

The last Labour Government changed that, increasing spending on the under-fives four-fold to fund the extension of maternity leave, the establishment of Sure Start Children’s Centres, and investments in both the availability and quality of childcare and early education. By 2010, all 3 and 4 year olds were entitled to 15 hours a week free part-time early education, and around 95% of them took it up. In a recent survey of Labour’s social policy record we track the impact of these policy changes. The findings point to improvements in children’s health and in cognitive, behavioural and other developmental outcomes, alongside narrowing gaps between disadvantaged social groups and others.

One part of Labour’s legacy was a much greater emphasis on early childhood across the political spectrum. The Coalition Government is committed to extending free places to more disadvantaged two-year-olds as part of their social mobility agenda, and has pledged to improve childcare quality and affordability (though in ways that remain under discussion). In future work at CASE we will assess the impact of Coalition policies in much the same way that we have done for Labour. Watch this space.

This week, though, Labour re-entered policy debate in this area with the eye-catching announcement that if elected in 2015 they would extend free childcare provision from 15 to 25 hours for all 3 and 4 year olds with working parents. The policy has been costed, and funds earmarked from a levy on bankers. Nevertheless it raises a question: is this the right way to spend precious government resources in an age of austerity?

In short, our work leads us to think that yes it is – for three main reasons. First and fairly obviously, it would sharply reduce the cost of childcare for parents, and childcare costs remain a major barrier to employment in many households with young children. Despite the investments of the last 15 years, and despite targeted subsidies for lower income working parents, parents pay far more for childcare in the UK than in many other countries, as our recent comparative international work reminds us.

Second, it would break down the barrier that currently exists between part-time and full-time settings, and this would also facilitate employment. Broadly, the 15 hours free provision can be taken either in nursery classes attached to primary schools (mornings or afternoons only), or as part of a longer day in a full daycare setting. Because not many jobs fit into 15 hours, and because not many full daycare centres have the flexibility to offer part-day places (which requires either spare capacity, or complicated arrangements to match parents up, or both) the result is too often a divide between settings catering to working families and those for children who have a parent at home. This split has an unintended consequence: instead of bridging a return to work for a mother nervously leaving her three-year-old for the first time, for example, the free places can operate as a stumbling block. If a child is settled happily in a nursery with morning availability only, chances are that a stay-at-home parent will postpone that search for work for another two years. If schools were funded to offer full day places for children whose parents moved into work, the stumbling block would be transformed into a stepping stone.

Both the financial assistance and the stepping stone effect would bring down the actual cost of the policy to the Treasury, as employment would rise, and therefore so would tax receipts.

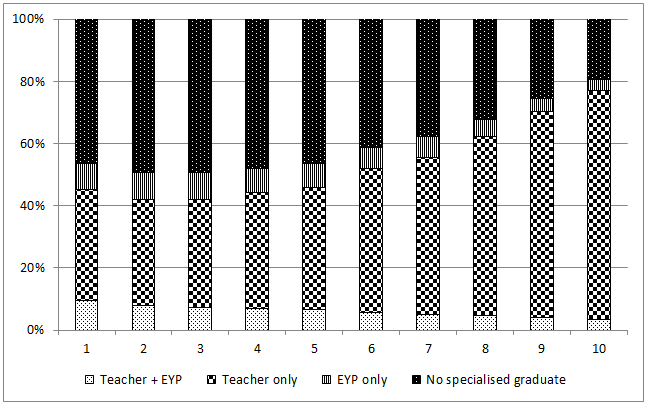

The third reason is equally important when we focus on child development: breaking down barriers between settings offering part-time and full-time places would reduce the social segregation which currently seems to be on the rise in early years settings. In a recent paper we find that (probably for the reasons outlined above) disadvantaged children are much more likely to access their free entitlement in a (part-time) school setting, while better-off children are more likely to attend a setting in the private or voluntary sector. This is good news for the disadvantaged children to some extent, because in the school settings nursery classes are led by a qualified teacher, and research tells us that this has a very important impact on children’s development. In the private and voluntary sector, little more than a third of children have a graduate in their setting. Figure 1 shows a rare story of a social gradient that seems to operate in favour of poorer children.

Figure 1: Presence of graduates in settings where 3 and 4 year olds access the free entitlement, by child’s decile of area deprivation. (highest level of disadvantage on the right.)

Source: Gambaro et al (2013) using Early Years Census 2011 and School Census 2011.

Notes: Figure refers to all children born between September 2006 and December 2007 who were receiving the free entitlement in all types of provision in January 2011.

Area deprivation calculated using IDACI scores for the Lower Super Output Area where child lives.

But the concentration of children from more disadvantaged backgrounds in the same settings makes it more difficult for teachers to deliver high quality provision. Our research highlights this: we find that Ofsted ratings, for example, are pushed upwards by the presence of a qualified teacher or Early Years Professional, but downwards by a higher percentage of disadvantaged children in the class. Wider research, such as that from the EPPE study, also emphasizes the importance of peer effects and the value of a social mix in the classroom.

Allowing working parents 25 hours of free provision would enable them to make use of school provision, improving the social mix in those settings, thus achieving positive effects not just on employment and incomes but also on social cohesion and child development. The next step would be to improve qualification levels in the private and voluntary sector, and fund these settings sufficiently to allow them to offer part-time as well as full-time places… But Labour’s first move is both sensible and a wise use of public funds, even in these straitened times.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Kitty Stewart is Lecturer in Social Policy at the LSE and a Research Associate at the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion.