Helen Goodman recently gave a response to Mike Savage’s new book, “Social Class in the 21st Century”, explaining how the current distribution of economic, social, and cultural capital creates an unequal society. Here, by outlining some of the ways through which such distribution creates a hierarchy of groups, she writes that a new approach will be necessary for a progressive government of the Left, which will need to have equality as a criterion for every policy initiative.

Helen Goodman recently gave a response to Mike Savage’s new book, “Social Class in the 21st Century”, explaining how the current distribution of economic, social, and cultural capital creates an unequal society. Here, by outlining some of the ways through which such distribution creates a hierarchy of groups, she writes that a new approach will be necessary for a progressive government of the Left, which will need to have equality as a criterion for every policy initiative.

As a politician on the frontline, I was delighted to give a response to the Great British Class Survey at the LSE. Mike Savage’s work tells us about how Britain is changing. By looking at the economic, cultural, and social capital different groups have, he demonstrates the multi-dimensional nature of class today.

A commitment to equality is central to the Left, whether because we believe, as the Declaration of Independence says, that it is self-evident that all men are created equal, or whether as Tawney says “The essence of all morality is this: to believe that every human being is of infinite importance.”

But in a country where the wealthiest 10 per cent of households own 45 per cent of the wealth – it’s clear we are failing. These problems are being intensified by a decade of Tory government – but simply reversing “Tory cuts” won’t do the trick. For far too long we have been trapped by the libertarian philosophy underpinning the Thatcher/Reagan era – which didn’t just re-shape our institutions, but also took hold of the popular imagination of what is possible, natural and necessary in public policy. Savage’s work opens up the possibility of a new approach for a progressive government of the left.

How class in Britain has changed

The emergence of a new elite – the 6 per cent – with high levels of every type of capital is pulling away from the rest of society. Its children will continue to have privileged access to wealth and influence. At the other end of the scale is a precariat –15 per cent or 9 million people – facing low pay, insecure and fluctuating work, with no cultural, economic or social capital.

Furthermore former distinctions between the middle and working classes are disintegrating with the emergence of five new ‘middle’ groups.

Britain is much more unequal than it was 30 years ago. A wall of money now separates the classes more steeply than before, which is almost impossible to scale. Emergent service workers and the precariat together comprise over a third of the population and I believe this goes a long way to explaining growing alienation from the political system.

We can’t have more equality of opportunity, without having more equality. Savage has shown that a person with the same professional position, skills and education will earn between £10,000 and £20,000 less than their peers if their father was a manual worker! “Education, education, education” is no longer the key engine of social mobility because it alone cannot tackle the accumulation of economic, social and cultural capital.

So the political task is to build up and distribute more equally each category of capital.

Economic capital

- Jobs

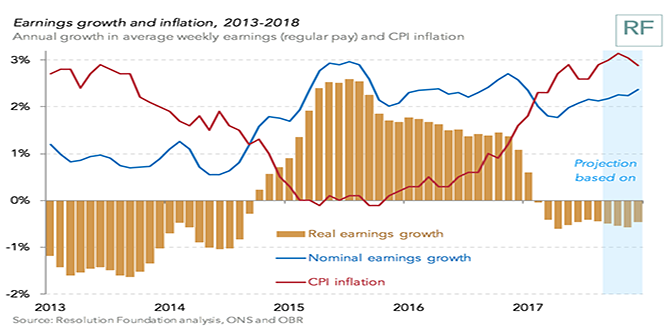

A good job is the most valuable asset a person can have. But a falling proportion of national income goes to wages – 40 per cent – while the share going to profits has risen to over 30 per cent. We need a legal framework which promotes better pay, conditions, and equal rights at work, and strong trade unions to enforce them. The New Economics Foundation showed that restoring union strength could add £27bn to GDP. Instead many people are in a state of insecurity which is detrimental to their incomes, health, wellbeing, and family life. Without a secure income, you can’t plan for the future.

The new model where “flexible labour markets” are the desiderata is not producing an economy which, as Ed Miliband said before the last election, should “work for working people”. This does not mean however that we can revert to an approach rooted in an out of date picture of the class structure.

- Housing

People need secure homes. Today many, even well-educated, young people are excluded from financial security and home ownership. A third of households in the private rented sector are those with children, meanwhile the average price in London is over half a million pounds.

Everyone now agrees that we need to build more – 300,000 homes each year. But politicians have been nervous about bringing prices down as a ratio of incomes and scaling up social housing – which is what we need.

At the last election Labour proposed to tackle land banking. Across the country, tying planning permission to affordable housing for locals is under discussion, and Frank Field argues that we should tackle youth unemployment by training 74,000 young bricklayers.

All these ideas need to be developed into a coherent plan.

- Redistribution

The Resolution Foundation has shown that redistribution makes Sweden more equal than the UK. Since 2010 the number of children living in absolute poverty has gone up by half a million and the Resolution Foundation forecast that by 2020 the number in relative poverty will rise to 27 per cent. The steeper the slope the harder it is move up it. Today wealth differences adversely affect both individual life chances and national economic performance.

The ONS reports that a quarter of the population are in ‘negative net wealth’ meaning that they have more debts than assets, while the top 10 per cent of households each have over a million.

We need a renewed commitment to the welfare state. And to avoid further inequality, we need a thorough review of the taxation of all wealth, alongside measures to help people to save and access financial services.

- Education

A good education is becoming more important in the knowledge economy, even though it may not change relative social positions as it did 40 years ago. We want Britain to develop new technologies, so maths and science are very important. At the same time it’s worth considering what machines cannot do and develop soft skills, art and creativity.

Yet today we have a shortage of maths and science teachers and artistic subjects have been removed from the core curriculum. This is where a left of centre government should invest. And we need university research to give us the edge internationally. Yet, as the Great British Class Survey shows, Russell Group entry criteria are to have the best and brightest, but their student base is consistently over-recruited from higher status backgrounds, and in turn their graduates are more likely to be ‘elite’.

Cultural capital

Cultural capital is important both because people use their knowledge of highbrow culture as a social signifier, and because culture is intrinsically valuable.

LSE colleagues Richard Layard, Daniel Fujiwara, Laura Kudrna and Paul Dolan have shown how arts and culture improve wellbeing significantly. Yet a study called Rebalancing Our Cultural Capital found that 14 times as much lottery money is spent per person in London as in the rest of the country.

In Lincolnshire a couple of years ago, the Arts Council spent 25p per person, meanwhile in London George Osborne has just put £5m of taxpayers money into a feasibility study for a new £250m concert hall just half a mile from the Barbican! The availability of good books, plays, and concerts on an affordable basis requires an effective infrastructure of national and local support.

Social capital and geography

We’ve now reached the stage where more investment in the south is producing congestion – at the same time as the north is being starved of resources. For every £5 spent on transport in the North East, £250 is spent on Londoners. And poor northern councils like Liverpool and Newcastle face cuts of 25 per cent while the Home Counties have seen their budgets rise. Handing over power without resources as in the current ‘devolution deals’ is a sham. The regions must be at the table when the resource allocations are agreed.

In a free society social capital is perhaps the most difficult area to influence. Social capital is developed by building ties across class boundaries, meaning we need equal opportunities at work; mixed public and private housing developments; schools which avoid social selection; universities which harness the talents of the whole nation; and cultural institutions which are open and available.

Conclusion

Wealth, housing, social contacts and cultural experience are dividing us into a hierarchy of groups. A left-of-centre government needs to have equality as a criterion for every policy initiative. We need to ask of every idea – will it make us a more equal or less equal society?

___

Helen Goodman is a British Labour Party politician, who has been the Member of Parliament for Bishop Auckland since 2005. She was the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Department for Work and Pensions until 2010 with responsibility for child poverty and childcare. She tweets as @HelenGoodmanMP.

Helen Goodman is a British Labour Party politician, who has been the Member of Parliament for Bishop Auckland since 2005. She was the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Department for Work and Pensions until 2010 with responsibility for child poverty and childcare. She tweets as @HelenGoodmanMP.

The solutions are the easy part. We pretty much know what needs to be done. The problem is finding the political will to do it. When FDR first introduced the New Deal (after massive demonstrations by various labor and socialist movements), it was just partially implemented because congress was nervous about implementing such socialistic measures as government funded programs and taxing the rich. Then came WWII with its highly motivating fear motive…then congress happily pumped tons of money into the production of armaments completely retooling the peacetime economy into a war machine. This provided lots of well paying factory jobs to people especially women (Rosie the riveter) who for the first time rose out of poverty. The multi-national corporate oligarchs have sucked up much of the wealth and political power of the world through neoliberal practices. As Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” There are two options for change: the ballot box or the barricades. Throwing in climate change, the globalization and robotification of jobs, the imperialistic creation of failed states world wide and you end up with quite a lethal social cocktail.