Ruth Lupton and colleagues at LSE’s Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) have recently published a research report examining changing prosperity, poverty and inequality in London during the 2000s. There was good news and bad news – here she sets out some of the main findings.

Ruth Lupton and colleagues at LSE’s Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) have recently published a research report examining changing prosperity, poverty and inequality in London during the 2000s. There was good news and bad news – here she sets out some of the main findings.

Like many global cities, London is a city of contrasts: high incomes and wealth on the one hand, and high poverty on the other. This was already the case at the start of the decade and become more so as London boomed during the early to mid-noughties. But from 2004, it began to accelerate faster. Just prior to the recession, London’s poverty rate (looking at household incomes after housing costs) was 27 per cent compared with 22 per cent for England. Inequalities between rich and poor were also greater than for the rest of the UK. Financial services drove London’s growth, while manufacturing continued to decline.

Many people expected London to be hit particularly hard by the recession, given the origins of the crash in the financial sector, and for the effect of that to be a reduction in inequality. But neither of these predictions turned out to be true. We looked at data from the Labour Force Survey, Households Below Average Income dataset, Wealth and Assets Survey and National Pupil Database, comparing 2010 with the period just before the crash in 2006-2008, to see how these trends played out in the distribution of education and qualifications, wages and earnings, incomes and wealth.

It is important to remember that errors of sample size and representativeness are higher when dealing with London than the country as a whole, so individual findings should not be emphasised in isolation. But two overall patterns are clear. First of all, in terms of the labour market, London did seem to be more resilient to the recession than other large urban regions. Full-time employment fell by less (-1.6 percentage points) in the capital than elsewhere in the country, and there was a smaller rise in unemployment (+1.2 percentage points). Part-time working increase, particularly among men, supporting a view that in London fewer full-time jobs often led to under-employment, rather than unemployment. London also seems well set for the future. At a time when qualification levels in the working-age population nationally were rising rapidly, those in London grew faster. For example, a 2.5 percentage point increase in the proportion with university degrees between 2006/8 and 2010, compared with 1.4 percentage points elsewhere. GCSE results in London’s schools were already better than elsewhere in the country by 2008, with a smaller attainment gap between pupils on Free School Meals and others. This remained the case in 2010.

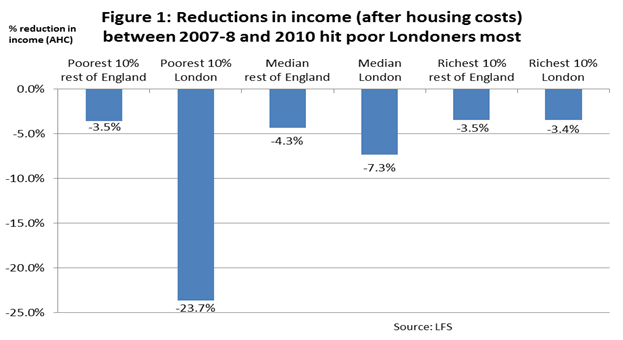

Second, inequality on earnings, incomes and wealth all widened, and more so in London than in the rest of England. In the case of wealth, this was because the wealthiest Londoners pulled away even further. Between 2006/8 and 2008/10 wealth levels among the least prosperous tenth of the population stayed flat in London, but grew by 14 per cent in England generally. Meanwhile, wealth among the top tenth of the distribution increased by 8 per cent in London, compared with 0.4 per cent in the rest of the country. As a consequence, the ’90:10 ratio’ for wealth in the Capital, which was already high (at 199) in 2006/8 had soared even higher by 2010 (to 215). But for earnings and incomes, rising inequality was driven by the worsening position of people at the bottom of the distribution. A particularly striking finding was the worse decline in household incomes, after housing costs, for low-income households in London. Figure 1 shows that while the incomes of people in the top tenth of the distribution were affected to much the same extent whether they lived in London or elsewhere, net incomes among those in the bottom tenth of the income distribution fell by a startling 24 per cent in real terms in London compared with only 3.5 per cent nationally.

So economic inequality widened both during growth and recession. But at the same time, poverty also became less concentrated in Inner London , and more evenly spread.

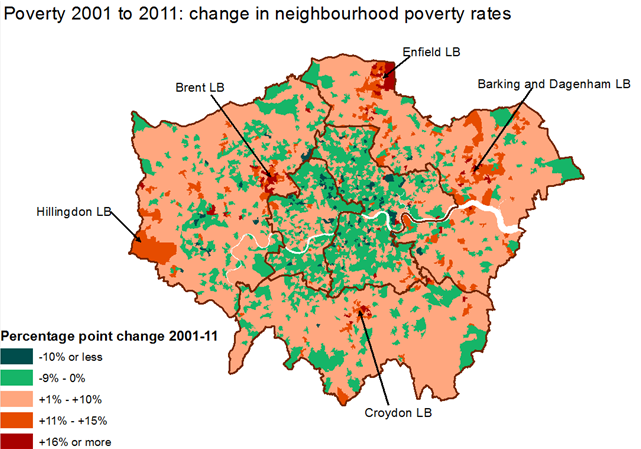

Mapping the proportion of households receiving Income Support and three other types of means-tested benefit shows that the greatest concentrations of poverty in 2001 were found in Inner East London. However, poverty rates, on this measure, fell considerably in the poorest inner-city neighbourhoods up to 2008, while increasing in less poor Outer London areas. This was mainly due to new house building and an influx of households that were less poor into Inner London, especially the Inner West. The numbers of poor households in these areas only fell a little – rather they were joined by new better-off neighbours.

As Outer London was hit harder than Inner London by recession, the shift of poverty into Outer London continued. Poverty went up across London between 2008 and 2011 as recession bit, but most in Outer London neighbourhoods. The map below shows how neighbourhood poverty rates changed across the whole decade 2001 to 2011 (with decreases shown in dark and light green, and increases in orange and red). In 2001, over three quarters (77 per cent) of the highest poverty neighbourhoods were in Inner east or west London. By 2011 this figure had fallen to closer to half (55 per cent). Thus a trend to decentralisation of poverty was evident before the Coalition’s welfare reforms, which are predicted to have this effect.

These findings raise important questions about the state of the UK’s capital city at the time the Coalition Government took power. On the one hand, they are positive, in terms of London’s economy, its labour market, and the qualifications of its inhabitants. Yet economic success does not seem to have translated into lower rates of poverty or inequality. The recession, despite its origins in the financial sector, appears to have worsened economic outcomes for those Londoners who were already poor, affecting the better-off less. As London returns to economic growth, questions will arise about how far widening inequalities can be redressed. At the same time, it will be important to better understand how the changing population in Inner London has affected poorer residents, and the ways that rising poverty in Outer London has impacted on housing, public services and communities.

The full version of this paper, by Ruth Lupton, Polly Vizard, Amanda Fitzgerald, Ludovica Gambaro and Jack Cunliffe is available here. This is one of a series of papers produced as part of CASE’s research programme Social Policy in a Cold Climate (SPCC) and was produced with funding from the Trust for London, one of the capital’s major charitable funders.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Ruth Lupton is a Professor at the University of Manchester and a Visiting Professor at the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (LSE) where she is leading a team of researchers examining the impact of the major political and economic changes since 2007 on poverty and inequality in the UK.

7 Comments