At the 2015 general election, the Conservative incumbent MP in Watford won 24,400 votes: over the preceding 15 months his campaign received major donations totalling over £312,000 – or nearly £13 per vote. Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Cutts look at these donations within the wider context of Tory fund-raising for their constituency campaigns.

At the 2015 general election, the Conservative incumbent MP in Watford won 24,400 votes: over the preceding 15 months his campaign received major donations totalling over £312,000 – or nearly £13 per vote. Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Cutts look at these donations within the wider context of Tory fund-raising for their constituency campaigns.

The media made much of the data published by the Electoral Commission in late May showing the amounts donated to the political parties during the first three months of 2015. Most of that money (the vast majority of it in sums of £2000 or more; small donations do not have to be declared) was undoubtedly given to assist the parties in their election campaigns. The Conservatives were clearly the main beneficiaries (they received over £15.4million: Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Greens, UKIP, PC and the SNP combined got less than £12million).

Focusing on the overall totals and the nature of the donors, however, the media paid virtually no attention to where within the Conservative party organisation the money went. Of the total donated during that crucial three-month period, £3.1million went to what the legislation terms local accounting units – in almost all cases constituency parties. This represents an average of £4,900 for each of the 631 constituencies the party contested, though some received much more than others.

The Conservatives’ advantage over their rivals in raising money for their campaigning is well-known. In January 2015 Ed Miliband accepted that they would probably outspend Labour by a ratio of some 3:1 (but that would be countered by greater activity on the streets and doorsteps – Labour’s 4 [later 5] million conversations). But how much were the Conservatives raising locally, and in which constituencies?

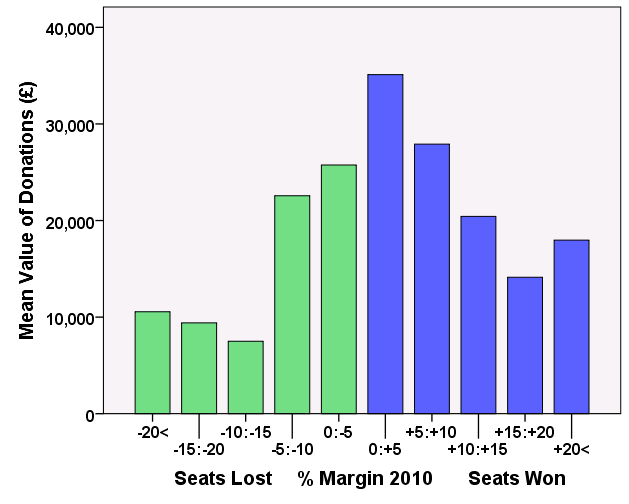

During 2014 and the first quarter of 2015, of the 631 constituencies in Great Britain (i.e. excluding Buckingham, held by the Speaker), the local Conservative party in 303 received no reportable donations at all, whereas at the other extreme one received 65: only 28 received more than ten, however. On average, each constituency in receipt of one or more donations got £20,870 during that 15-month period. But, as the graph below shows, the average varied according to constituency marginality.

The constituencies have been placed into ten groups, according to the margin of defeat (shown in green on the left) or victory (in blue, on the right) in 2010. For each of the five groups on either side of the diagram, more was raised in large donations in seats that the Conservatives won in 2010 than in those that they lost (an average of over £35,000 in those that they won by less than 5 percentage points, for example, compared to just under £26,000 in those lost by the same margin). Conservative donors were apparently more prepared to give money to local campaigns where their party was defending the seat than to those where they were hoping to gain further representation, even in the most marginal constituencies – even though David Cameron made clear that he was fighting for an overall majority, which meant he needed a net gain of 23 seats.

So which constituency parties got most? Of the forty most marginal constituencies where they lost in 2010, three received over £70,000 in large donations over the fifteen-month period: £72,774.56 at Chippenham, where the Liberal Democrat incumbent was unseated; £75,000 at Nottingham South and £79,000 at Westminster North – in both of which the Conservative candidate failed to replace Labour’s. One other received more than £50,000 – Morley and Outwood, where Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls was defeated – and five more got more than £30,000.

Eleven of the constituency parties in those marginal seats – all on the Conservative target list at the start of campaigning in 2014 – received no large donations, however, including Wells and Somerton & Frome, seats both won by the Conservatives from the Liberal Democrats, and Plymouth Moor View, where the Labour incumbent was removed. Those local campaigns may have been well-funded without large donations – the full details on campaign expenditure and local party accounts will not be available for some months – but they show that large donations were not necessary to ensure success (nor, as the two seats quoted earlier show, did they necessarily bring success where they were obtained).

What of the 40 marginal seats where the Conservatives were defending a small majority – most of which were Labour targets? Only four – Broxtowe, Waveney, Morecambe & Lunesdale, and Montgomeryshire, none of them lost to Labour – received no donations. Of the other 36, eight received more than £50,000 – including the highly marginal Oxford West & Abingdon (£62,000) – but by far the largest total went to Watford, won by 2.58 percentage points in 2010 in what was one of that election’s closest three-party fights. Labour hoped to win there in 2015 (but its candidate received not a single large donation during the 15 months before the election!), as did the Liberal Democrats, whose candidate was the popular local mayor (who received £48,995 in 2014 and a further £12,300 in the first quarter of 2015). Over the fifteen months 65 donations to the local Conservatives totalling £312,560 were received. This was much more than could be spent on the final months of the campaign – from late December 2014 on, legally only £40,346 could be spent promoting candidate Richard Harrington’s cause, leaving over £270,000 to be spent before then, or on other things.

Clearly the local party, and probably the regional and national party organisations too (not least those involved at David Cameron’s Leader’s lunches whose job it was to convince potential donors to give generously – and to where), were able to attract a great deal of money to this apparently crucial seat in the party’s strategy – much more so than in the 21 more marginal seats it was defending. According to the Electoral Commission’s classification of donors, 18 of the 65 donations received were from companies (totalling £98,000), 7 from unincorporated organisations (£38,000), 39 from individuals (£172,000), and 1 from a limited liability partnership (£5,000 from AHV Associates).

So who were these donors prepared to provide substantial sums to try and ensure another Conservative victory in Watford? AHV Associates is a ‘corporate finance boutique’ based in London’s Mayfair. Twelve companies provided donations: only two are based in Hertfordshire with most of the remainder in London, many are involved in real estate and other investments. Donations were also received from the Stalbury Trustees, a registered company established by the Cecil family which makes extensive grants to Conservative parties and individual politicians. Among the unincorporated associations the main donors were the Watford Business Club, which gave £24,750, and the United and Cecil Club (£5,000), a major Conservative supporter. (The United and Cecil Club gave £15,000 of the total £57,956.13 given to the Morley and Outwood local party, where Ed Balls was defeated; hedge fund manager Hugh Sloane gave a further £22,517.92.)

Among the major individual donors were: Nikolaas Allen, a Hertfordshire businessman with publishing interests, who gave five donations totalling £6,725; Paul Brett, who in addition to two donations totalling £22,500 also gave to other constituencies – including Michael Gove’s Surrey Heath; Peter Batey, a businessman with strong Chinese links, formerly associated with Sir Edward Heath; and hotel owner Roy Peires. Very few of these donors have any obvious close links to Watford, and they illustrate either or both of the power of the local Conservative Party in canvassing financial support for its cause and the party’s central organisation for directing potential donors to a worthy destination for their money.

But Watford was an exception. Elsewhere, the big money largely went to constituency parties where it wasn’t really needed. The three others that received more than £100,000 each over the period were all safe seats – Richmond Park (Zac Goldsmith’s seat, with a 6.9% lead in 2010: not a very safe seat but the Liberal Democrats were unlikely to win it back; Goldsmith increased his majority from 4,000 to 23,000), Tatton (George Osborn, 32%), and The Cotswolds (Geoffrey Clifton-Brown, 24%) – and another 30 got donations totalling £50,000 or more. Of the 34, 29 were Conservative-held seats, 12 won in 2010 with majorities of 10 percentage points or more (and eight by 20 points or more). Much of the money donated to Tory campaigns thus went to constituency parties where it would have had little impact: they were going to win there – and probably by large margins – in any case. George Osborne and Michael Gove could more readily attract funds – perhaps without trying very hard – than many of Tory MPs defending small majorities, let alone those hopefuls trying to win seats from either Labour or the Liberal Democrats.

The Conservatives clearly outspent the other parties by a large margin at the 2015 election nationally. But the gap was not as wide in large donations to their constituency parties. In the fifteen months ending on 31 March 2015 local Tory parties received £4.5million: Labour’s constituency parties received £3.6million during the same period, and the Liberal Democrats’ £3.8million (although in the last months – January-March 2015 – Conservative appeals for more money to be given to constituency parties clearly paid off; their local organisations received almost twice as much money as all of their opponents combined).

But there is a paradox. Much of that money the Conservatives raised was, in one sense, wasted since it was given to candidates who were almost certainly going to win – and in some cases, like Watford, it was more than enough to win the seat several times over. (Harrington got 19,291 votes in 2010 and 24,400 in 2015 – so his ‘extra’ 4,709 votes cost £66 each!) And then there were the seats where no large donations were received, and yet the incumbent party (in some cases the incumbent MP) was unseated by the Conservatives (perhaps because of targeting of voters there from the centre rather than by the local party); and there were those marginal seats in receipt of large sums but the Conservatives nevertheless failed to win. Was that because the amount of money was not always matched by the amount of activity on the ground, or….? Until we see the total returns on campaign spending and the local parties’ accounts for 2014 later this year (and the 2015 accounts in mid-2016) we won’t know, but at present it does seem that the Conservatives didn’t make the best use of those £4.5million made available by large donors.

Large donations to constituency Conservative parties were not necessary conditions for electoral success, therefore. Some attracted large sums, but their candidate lost; others attracted none, and their candidates won! Clearly, donations are only part of the story. Much of the campaigning in the party’s target seats was undertaken from central headquarters, with bespoke communications sent directly to identified potential supporters. In such cases, money given to the local campaign was perhaps little more than icing on the cake – it enabled more leaflets to be printed and distributed (as long as there were enough volunteers available to deliver them) and posters displayed; what would have happened in Watford without all that money? It may have made the difference in some cases, of course, but in others it was clearly wasted – allowing well-known candidates (including Cabinet ministers) in safe seats to run much more intensive campaigns than necessary. But it may well have been that in some places where it was needed none was forthcoming and the local campaign faltered as a consequence.

Over recent elections, the Conservatives – following the example of their main opponents – have worked hard to focus their campaign resources on the ‘swing seats’, but they have yet to achieve this fully: much achieved, much more to be done. Despite their increased efforts to direct their local campaigns from the centre – focused on target seats – most of the resources deployed by local parties are raised locally and, it seems, many resource-rich organisations are resisting redirecting money to poorer, yet electorally more deserving, neighbours.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Charles Pattie is Professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield, specialising in electoral geography.

David Cutts is a Reader in Political Science at the University of Bath. His research interests include party and political campaigning, electoral behaviour and party politics, party competition, ethnic minority political integration, and methods for modelling political behaviour and public opinion.

David Cutts is a Reader in Political Science at the University of Bath. His research interests include party and political campaigning, electoral behaviour and party politics, party competition, ethnic minority political integration, and methods for modelling political behaviour and public opinion.

1 Comments