Why was the Irish 2011 election considered ‘truly seismic’ but at the same time regarded as mattering so little? An important and revealing contribution, How Ireland Voted 2011 covers the dramatic decline of Fianna Fail, the rise of Fine Gail and Labour and the left more generally, and high levels of volatility. Reviewed by Daphne Halikiopoulou.

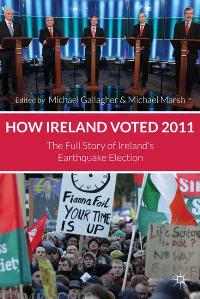

How Ireland Voted 2011: The Full story of Ireland’s Earthquake Election. Michael Gallagher & Michael Marsh. Palgrave Macmillan. October 2011.

How Ireland Voted 2011: The Full story of Ireland’s Earthquake Election. Michael Gallagher & Michael Marsh. Palgrave Macmillan. October 2011.

How Ireland Voted 2011: The Full Story of Ireland’s Earthquake Election is an edited collection that tackles the various aspects of what the editors term ‘the unprecedented’ Irish election of 2011: unprecedented both because of the interest that it generated and its potential to produce dramatic political change. The volume is the latest in the How Ireland Voted series, and the thirteen contributions cover a wide range of issues surrounding the election, including pre-election developments (chapter 1-3), the electoral campaign (chapter 4-6), result analysis (chapter 7-8), the electoral system (chapter 9), the role of women in the campaign (chapter 10), the election of the Upper House (chapter 11), the formation of the new government (chapter 12) and the comparative dimension of the election, both in terms of previous Irish elections and West European politics (chapter 13).

Michael Gallagher (chapter 7) lists a number of factors that made this election ‘truly seismic’: volatility was higher than any previous election; Fianna Fail suffered significantly, receiving its lower ever share of the votes and number of seats; Fine Gail on the other hand gained more than it ever has, becoming the strongest party and winning its highest ever number of seats. The election also witnessed the rise of Labour which achieved second party status and won its highest seats ever, pointing more generally to the left receiving high levels of support.

The volume is well put together producing a coherent whole; if some of the chapters are a little descriptive they provide a good context within which to provide a good analysis of the election and its results. Together the chapters make an informative study that provides an interesting multi-dimensional analysis. Taken separately, chapters 7, 8, and 13 detail the three main trends of the 2011 election: the dramatic decline of Fianna Fail, the rise of Fine Gail and Labour and the left more generally, and high levels of volatility.

In their attempt to address the causes of the first two trends, Michael Marsh and Kevin Cunningham in chapter 8 examine the voters themselves and their preferences by analysing campaign and exit polls. The collapse of Fianna Fail can be explained along the lines of a classic case of the electorate punishing the party for making bad economic decisions, but the second trend is more complex and although the authors examine a number of possibilities, the answer remains unclear. The chapter considers the effects of party competition, voter and party alignment, and demographic and class factors in order to examine the main patterns of the election. The overall outcome hardly points to a typical left-right divide: unlike other European countries, the Labour party does not dominate any particular class. In fact the authors find very little sign of realignment in accordance to class. Perhaps the most interesting observation is that settling on the alternatives has involved a great degree of volatility and decisions made in the last months and weeks leading up to the election.

Peter Mair in chapter 13 examines the comparative dimension of the election and shows how it is characterised by both significant change but also continuity. Compared to 2007, the 2011 election brought massive change, but perhaps one that is not so difficult to understand. As expected, the election is much the result of a severe economic crisis which tested the governing party and resulted in high record shift in votes. Mair agrees with Gallagher that one of the main features of the election is the remarkably high level of volatility. The fact that the average level of volatility in Ireland has tended to be below of that in Western Europe is an indication of a more widespread drift towards electoral instability in Europe. Drawing a comparison between levels of volatility in European countries across time, Mair finds that the 2011 Irish elections are unusual even by European standards: the third most unstable election in postwar Western Europe.

In terms of government formation however, the results actually suggests continuity. Over time party competition in Ireland has come to revolve around the opposition between two blocs: a Fianna Fail plus bloc and a Fine Gail Labour bloc. The 2011 result signals a reversion to the more traditional pattern, a Fine Gail –Labour coalition. Despite the economic crisis, the collapse of Fianna Fail and the dramatic nature of the elections, political opposition in Ireland continues to be organised along familiar lines. In addition the electoral upheaval seems to have signalled a partial electoral realignment, a shift towards the left which is unusual for Ireland; given the Eurozone crisis and the austerity this has entailed, this may not be so surprising.

Overall the volume’s comparative outlook, both across time and across Europe is one of its stronger features. Placing the election in a broader context, we may draw parallels and identify patterns that help understand emerging trends both in Irish and European politics, especially at times of crises. We may understand how and why the economy has been significant in determining voting patterns, we may comprehend changing voting alignments, the importance of high levels of volatility, and how these matter for voting preferences. But most importantly we can appreciate why, as Peter Mair argues, both in itself and comparatively, the Irish 2011 election is so seismic and at the same time, given the wider European crisis and the terms laid down by the EU, the ECB and the IMF, why it matters so little.

How Ireland Voted 2011: The Full story of Ireland’s Earthquake Election. Michael Gallagher & Michael Marsh. Palgrave Macmillan. October 2011.

Find this book: ![]() Google Books

Google Books ![]() Amazon LSE Library

Amazon LSE Library

Daphne Halikiopoulou is Fellow in Comparative Politics in LSE’s Department of Government. She obtained her PhD from the LSE in 2007. Her area of expertise is in comparative European politics, British politics and qualitative methodology. Her research focuses on the sociology of religion, nationalism and its relationship with the extreme right and extreme left, immigration and the criteria for inclusion in the nation. She is author of Patterns of Secularization: Church, state and Nation in Greece and the Republic of Ireland and Nationalism and Globalization: Conflicting or Complementary (co-edited with Sofia Vasilopoulou, forthcoming).