Nicholas Allen discusses Boris Johnson’s first major reshuffle and explains why it has resulted in a relatively high degree of continuity within cabinet. Nevertheless, the ‘constructive dismissal’ of Sajid Javid could have long-term repercussions: while in the short term Javid is unlikely to pose a threat from the backbenches, this may well change once Johnson is no longer associated with electoral success

Nicholas Allen discusses Boris Johnson’s first major reshuffle and explains why it has resulted in a relatively high degree of continuity within cabinet. Nevertheless, the ‘constructive dismissal’ of Sajid Javid could have long-term repercussions: while in the short term Javid is unlikely to pose a threat from the backbenches, this may well change once Johnson is no longer associated with electoral success

Boris Johnson is an incautious prime minister. Since entering 10 Downing Street last summer, Johnson has chanced his arm in his dealings with MPs, ministers, the monarch and the electorate. His latest reshuffle is yet another indication of his penchant for risk-taking.

Depending on how you define them – and there is no universally accepted definition – Johnson has conducted four cabinet reshuffles since becoming prime minister. The first came immediately after he assumed the premiership in 2019. In a calculated bid to signal both a fresh start and his own commitment to delivering Brexit, he dismissed around a dozen ministers from Theresa May’s cabinet. It was a brutal and risky assertion of prime ministerial power.

The second reshuffle came less than two months later, this time as a response to the fallout from other chancy actions. Amber Rudd, the work and pensions secretary, and Jo Johnson, the universities minister and Boris’s younger brother, both quit over concerns about the Prime Minister’s approach to Brexit, specifically the (ultimately unlawful) decision to prorogue parliament for five weeks and the removal of the whip from 21 Tory MPs. Johnson was forced to plug the resulting gaps, which he did by bringing Thérèse Coffey and Zac Goldsmith to the cabinet table.

The third reshuffle, if you can call it that, followed the Conservatives’ stunning victory in December’s general election. Rather than overhaul the cabinet, as almost all successfully re-elected prime ministers have done, Johnson merely filled the vacancy created by Alun Cairns’ resignation as Welsh secretary in November. It was made clear that a more thorough reorganisation would happen after Britain exited the European Union on 31 January 2020.

The February 2020 reshuffle

The fourth reshuffle, the post-election reshuffle proper, finally came in mid-February. It was inevitably trailed by some commentators as the St Valentine’s Day massacre – and it largely lived up to the hype. Of the 33 ministers who had attended cabinet immediately before the reshuffle (which effectively began on 31 January with the abolition of the Department of Exiting the European Union), only 22 remained.

Nicky Morgan, the culture secretary, had already announced her intention to leave. Three others – James Cleverly, Zac Goldsmith and Kwasi Kwarteng – retained ministerial jobs but lost their cabinet-attending status. Five others – Geoffrey Cox, Andrea Leadsom, Esther McVey, Julian Smith and Theresa Villiers – were sacked outright, while Jake Berry quit the government after being moved involuntarily from his role as minister for the ‘Northern Powerhouse’. Last but certainly not least, Sajid Javid dramatically and unexpectedly resigned as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Twenty-six ministers now attend cabinet. This number is not quite the ‘six or seven people’ that Dominic Cummings, the Prime Minister’s chief special adviser, has advocated in the past. Nevertheless, it is a reduction of sorts, and it has been bought at the cost of several bruised egos and thwarted ambitions.

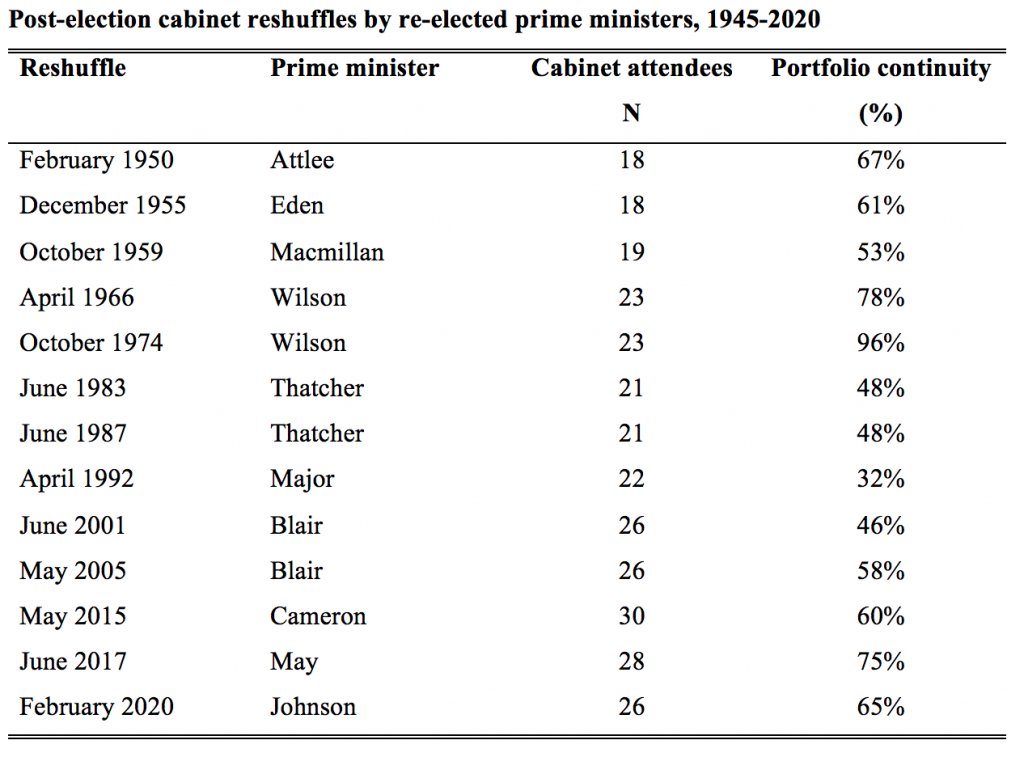

Amid the changes, there was a relatively high degree of continuity among the ministers who remained in cabinet. In terms of portfolio continuity – the proportion of individuals holding essentially the same job in the post-reshuffle cabinet as before – Johnson’s was the second least disruptive post-election reshuffle since October 1974. Only Theresa May’s cabinet saw less churn after she lost her majority in the 2017 election.

Man overboard

The reshuffle will be remembered for Sajid Javid’s shock resignation, however, not the relatively high degree of continuity. The general assumption had been that the chancellor’s position was secure. Johnson had only appointed him in July 2019, and Javid was due to deliver the budget in less than a month. But when Johnson asked the chancellor to sack all his advisers, Javid quit.

The Prime Minister had seemingly wanted to keep his chancellor in post and assert greater control over the Treasury. If that was the case, Javid was having none of it. In an apparent swipe at his successor, Rishi Sunak, Javid told reporters that he was unable to accept the Prime Minister’s conditions for staying on, and added: ‘I do not believe any self-respecting minister would accept those conditions.’

Prime ministers and chancellors

The relationship between a prime minister and his or her chancellor of the exchequer is of central importance to a government’s fortunes. The Treasury’s hand on the purse strings gives it a crucial role in coordinating policy across Whitehall. Its economic role gives it enormous potential influence over the government’s electoral fortunes.

The chancellor is also usually a significant politician in his own right and often a potential candidate for the top job. Prime ministers need to appoint and manage them with care. Excluding Rishi Sunak, 24 men have been appointed chancellor since the 1945 general election. Of these, ten left office either because their party lost an election or, in the case of Harold Macmillan, John Major and Gordon Brown, because they became prime minister. One chancellor, Iain Macleod, died in office, and another, Sir Stafford Cripps, resigned because of failing health. Six others resigned, all in very different circumstances. Otherwise, post-war prime ministers have moved or sacked a chancellor on only six occasions: Rab Butler, James Callaghan and Sir Geoffrey Howe were all moved, while Selwyn Lloyd, Norman Lamont and George Osborne were all dismissed. Prime ministers do not shuffle their chancellors lightly.

By some accounts, Sajid Javid’s departure was akin to a constructive dismissal. In this respect it bears a resemblance to the resignation of Nigel Lawson, who quit as Margaret Thatcher’s chancellor in 1989. Both departures involved advisers. But whereas Johnson wanted to deprive Javid of his, Lawson wanted Thatcher to dismiss her economics adviser, Sir Alan Walters, for publicly disagreeing with Treasury policy. When Thatcher refused, Lawson felt he had no choice but to go.

Where does the reshuffle leave Johnson?

There is more than a whiff of Dominic Cummings’s style of politics in Javid’s departure. The Prime Minister’s adviser is no respecter of convention or other people’s egos. Whether Javid was targeted or collateral damage in the reshuffle, Number 10 has clearly emerged stronger and with greater control over the Treasury.

There is also more than a whiff of Johnson’s risk-taking in the reshuffle. The Prime Minister must have known that his demands on Javid made the chancellor’s resignation a possibility. He must also have calculated that Javid, if he walked, would not pose a threat from the backbenches. That was probably a reasonable judgment given Johnson’s personal standing in the wake of the 2019 general election.

Yet, the long-term risks in Johnson’s handling of the affair are real. On the one hand, dispensing with rivals and centralising power in 10 Downing Street will make it harder for him to share the blame when things go wrong. On the other hand, every minister dismissed or belittled increases the pool of enemies on the benches behind him. Johnson will be safe for as long as he is associated with electoral success. But as Margaret Thatcher found to her cost, ambitious former ministers can strike against a prime minister when circumstances change.

________________

Nicholas Allen is Reader in Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Nicholas Allen is Reader in Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Boris Johnson’s first PMQs by UK Parliament, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.