In a major speech that has already furrowed brows amongst the Tory right wing, Ken Clarke set out proposals for wide-ranging criminal justice reform. Simon Bastow listened to his speech and sets it against the overall picture of pressures on the Ministry of Justice, where 25 per cent cuts might come, and the future of the prisons system especially.

In a major speech that has already furrowed brows amongst the Tory right wing, Ken Clarke set out proposals for wide-ranging criminal justice reform. Simon Bastow listened to his speech and sets it against the overall picture of pressures on the Ministry of Justice, where 25 per cent cuts might come, and the future of the prisons system especially.

It’s still early days in terms of the government’s plan for reform to the criminal justice system, but on 29 June the Secretary of State for Justice, Ken Clarke, outlined some of the big themes in a speech to a select group of criminal justice professionals, academics and journalists at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies at King’s College London. In a relaxed and self-deprecating style, the Secretary of State talked about how he and his team were ‘steadily forming a sense of purpose’ about the direction of reforms, and how these would feed into the wider economic imperative of reducing the cost of public services.

Apparently it is not yet known how much his department will be expected to save in the coming years. However, it is reasonable to assume that the department will not be exempt from demands for cuts of up to 25 per cent. Other blog contributors have already doubted if cuts of more than 20 per cent are in fact achievable. But let’s take the government at its words and assume for the moment that from an annual departmental budget of £9 billion in 2008/09, a credibility-defying sum of more than £2 billion can in fact be removed.

Clarke outlined wide-ranging measures which will form the basis for a Green paper on reform in the autumn. These will impact key areas of expenditure for the Ministry, including prisons and probation, courts, and legal aid. The Table below shows the current level of expenditure in each of these areas, and my view of how savings may be achieved.

Overview of Ministry of Justice resource budget expenditure 2008/09, and notional cost savings for main expenditure areas

| 2008/09 Outturn (£ millions) | (25 per cent saving in millions) and how it might be achieved | |

|---|---|---|

| Departmental resource budget Of which: | 9,070 | (2,270) |

| Prisons | 2,450 | (1,120) Reduction in size of the prison population, rationalizing of estate, greater use of more cost-effective community sentences |

| Probation | 870 | |

| NOMS HQ | 1,160 | |

| Courts | 1,240 | (310) Rationalization of the court estate and reduction in staff |

| of which Staff and Judiciary costs | 860 | |

| Legal aid (Community Legal Service, Criminal Defence Service, and other costs) | 1,910 | (480) Comprehensive review of legal aid provision in line with other countries |

| Other expenditure (Youth Justice Board, Tribunals, and other items) | 1,440 | (360) Further rationalisation of tribunal system and YJB |

Source: Ministry of Justice Departmental Report 2008/09. Figures are estimated outturn for departmental resource budget DEL (excluding annual managed expenditure (AME) and capital expenditure). All figures are rounded to the nearest 10 million.

Through the National Offender Management Service (NOMS), prisons and probation currently account for more than half of the MoJ’s resource expenditure. Achieving 25 per cent cuts in this area would entail a massive reduction of more than £1 billion, equivalent to what the government was spending on prisons in real terms in the late 1990s, when the prison population was around 65,000 (as opposed to 85,000 today).

Reducing the size of the prison population has clearly got to be a critical part of this plan. It would be patently impracticable to suggest otherwise. It is interesting to see that prison reformers and the Secretary of State have found themselves in a meeting of minds on this point, but seemingly for very different reasons. Prison reformers seek a reduction in the size of the prison population as an objective in itself. Clarke, however, was quick to point out that he has no view on the correct size of the prison population, only that society should be making the most ‘cost-effective’ use of prison sentences.

What the minister seems to be saying, quite skilfully it seems, is that if population needs to decrease in order to get to reach optimal cost-effective point, then so be it. But this should not be mistaken as him advocating a reduction in the size of the prison population per se. This is presumably how a reforming Conservative Justice Minister spins prison reform to the most right wing members of his own party! It is just a collateral by-product of doing things more cost-effectively.

Let’s say that the prison population can be reduced over time, and that rationalization can lead to cost savings across the prison estate. The next issue is how community punishments can be made credible enough to take up the slack. Senior members of the judiciary and magistracy have made positive statements about the need for some kind of fundamental reform to sentencing guidelines and strengthening community punishments, and a planned sentencing guidelines review may provide some optimism on this point. The Scottish Parliament has just voted to end all prison sentences of less than three months north of the border, which might be a useful step to follow in England and Wales also.

However, serious questions remain about the capacity for probation services to manage the displacement effects of reduced prison population. Senior probation managers point to a chronic overload of cases, comparative under-resourcing, weak management capabilities, and low staff morale – all of which have combined to severely limit the extent to which probation services can respond in caseloads.

Finding management efficiencies in probation may be realistic to some extent. But many would argue that the reason why community sentences have looked so much better value for money over the years has as much to do with the fact that they have been chronically under-resourced and under-nurtured, and given little political backing if anything at all goes wrong (as it inevitably must from time to time).

It is difficult therefore to see how a radical capacity increase in community sentencing is going to happen without much closer parity in funding between prisons and probation – that is, moving from the current 3 to 1 ratio, to something more like parity of funding between the two services. Yet the Secretary of State could not promise any considerable increase in investment for community sentencing in the current economic climate. The gap would have to be closed at the expense of prisons, and this, quite legitimately, will be resisted by governors, managers and staff working in the prison system, who are themselves already under some degree of capacity stress.

Much has been said about the increase in the size and cost of the National Offender Management Services HQ in recent years. So it would seem reasonable to advocate downsizing in the massive £1.1 billion expenditure absorbed by the NOMS HQ architecture. It is a startling fact that the entire English courts system operates on roughly the same budget as the NOMS headquarters.

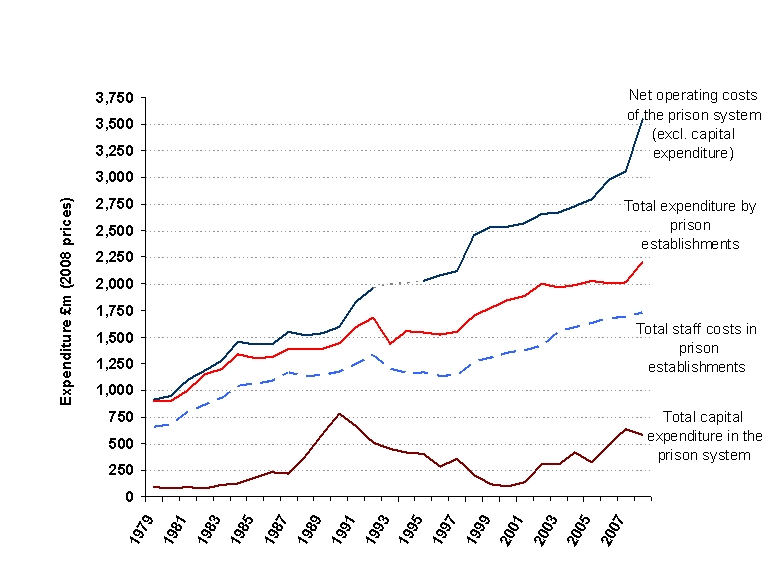

Expenditure in real terms on prisons since 1979 Source: Collated and computed from the last 31 years of Prison Service and NOMS annual reports, and Home Office and Ministry of Justice departmental reports.

Source: Collated and computed from the last 31 years of Prison Service and NOMS annual reports, and Home Office and Ministry of Justice departmental reports.

My chart above shows that expenditure by the centre as a proportion of total spending on the prison system has increased gradually since the Prison Service was made an Executive Agency in 1993. Much of this expenditure has gone into introducing the performance and standards regimes, which have undoubtedly improved the quality and consistency of the prison experience since the early 1990s. Much of this expenditure has also played an important part in radically improving the performance of the prison system, and to complain about this increase, as many academics and media critics do, is to forget this basic point.

In other areas, the Secretary of State outlined plans to rationalize the courts estate, both in terms of making much cost-effective use of the available capacity, and decommissioning and modernizing existing assets in partnership with private contractors most likely through PFI. The National Audit Office report on the PFI Laganside Courts project in 2005 illustrates nicely the rationale and operational benefits behind this approach – although actual cost savings were hard to establish. Rationalization of the courts would involve a considerable reduction in court staff, and would most likely meet with professional resistance from the judiciary.

Finally, the Secretary of State expressed a clear intention to reform the legal aid budget, arguing that legal aid payments per annum per capita are considerably higher than in other comparable countries. The cut here is likely to be quite brutal reduction in the size of payments, and it will have considerable impacts on access to justice for less well-off people. There is also scope for cost savings through better administration of payments. (The NAO reported around £25 million worth of legal aid over-payments in 2009, although this is small beer in comparison to the amount of cutbacks envisaged in this area).

Clarke and his MoJ team plan to consult on these issues during the summer, and then to publish a Green Paper in the autumn.

1 Comments