The first ever large-scale study on public attitudes to homelessness has revealed that public opinion tends to overlook the relationship between homelessness and poverty in favour of a more fatalistic view that blames individual circumstances and poor choices. Lígia Teixeira writes that if we are to end homelessness once and for all, then we need the public’s support. She explains the third sector’s role in that effort.

The first ever large-scale study on public attitudes to homelessness has revealed that public opinion tends to overlook the relationship between homelessness and poverty in favour of a more fatalistic view that blames individual circumstances and poor choices. Lígia Teixeira writes that if we are to end homelessness once and for all, then we need the public’s support. She explains the third sector’s role in that effort.

In 2017, homelessness finally returned to the political agenda. With 160,000 households experiencing the most acute forms of homelessness across Scotland, England and Wales, it’s not a moment too soon. If, like me, you value evidence-driven homelessness policy, you’ll know that two trends are largely responsible for this recent rise: a shortage of affordable housing and the impact of welfare reforms and cuts.

Fifty years of campaigning, targeted services, and focused research have given us insight into what it might take to end homelessness. We know that as beneficial as it is to support one person or family at a time, unless we address the structural causes – such as the lack of affordable homes, low wages and irregular work, inequality, and inadequate services for people in poverty – homelessness will continue to be a problem in our society.

Despite this, a new study conducted by the FrameWorks Institute for Crisis reveals that the public still incorrectly believe that individual factors such as a person’s character and personal choices are largely to blame. In short, the public do not believe that homelessness can be ended, and this fundamental misconception may be preventing our work from progressing.

The study shows how the public see the ‘typical’ homeless person as an outsider or victim – someone whose circumstances place them in a separate category of society. When asked about their expectations for the future, most see homelessness as an impossible problem that personal actions can do very little to solve.

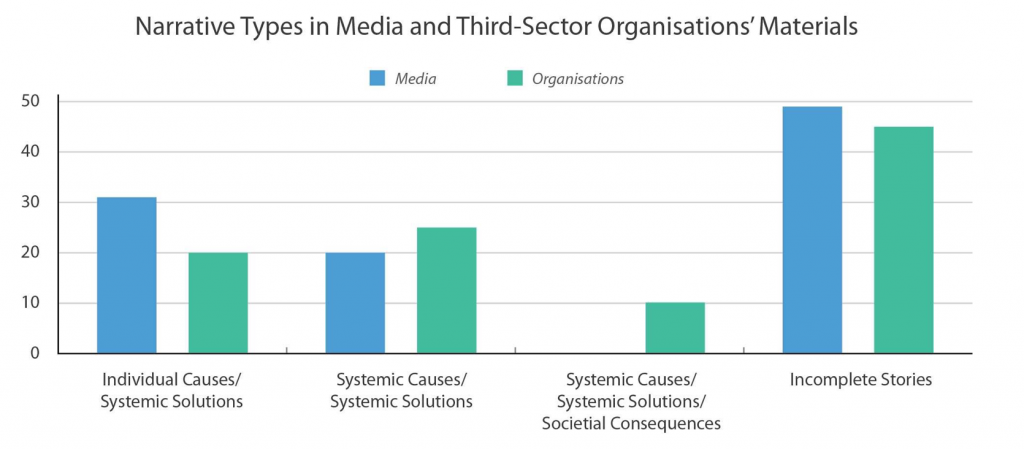

What’s also surprising is that communications from sector organisations and the media are inadvertently supporting these paradigms and likely increasing the public’s sense of fatalism about homelessness. Why? Largely because we tend to give weight to stories emphasising the depth and scope of the problem, headlining its prevalence and individual impact while omitting evidence-informed solutions. By doing so we are allowing the public to give in to despondency and to accept that homelessness is just an inevitable part of modern society.

The good news is that we have the power to change this by telling different kinds of stories. The research shows that people are able to think in more productive ways about homelessness when presented with a systems view on the subject.

Currently, only one-third of the sector’s communications applies a systems perspective on homelessness, suggesting that we’re missing valuable opportunities to illustrate consequences and solutions, and to show how wider society benefits from collective action. Similarly, media stories tend to focus on the individual impact of homelessness to the detriment of its wider causes.

This matters because people are more likely to engage and take action if they understand that not everyone is at equal risk of homelessness and that policy choices make all the difference.

Now that homelessness is near the top of the political agenda, we need to hold politicians to their promises and make sure they are carried through – and this work must include better public engagement to galvanise support and provide people with even more ways to get involved.

The study suggests that we can improve how we communicate about homelessness by following these simple rules:

- Challenge the public’s image of a ‘typical’ homeless person. We need strategies to disrupt the public’s archetypal image of the homeless person: the middle age man who sleeps rough. This includes avoiding images that reinforce the public’s stereotypes of homelessness;

- Discuss the social and economic conditions that shape people’s experiences, and avoid talking about personal choices and motivation (it may seem like a good idea but the study shows this strategy backfires);

- Talk about the societal impact of homelessness as well as the individual. Highlighting collective solutions will help combat fatalism and encourage the belief that collective action can drive change;

- Explain prevention and build a story that people outside of the sector can take up. The homelessness sector cannot end homelessness on its own – better collaboration with people in other related fields will help improve outcomes.

- Talk about how systems are designed – and can be redesigned. The public should understand that the current situation is largely due to policy decisions and that we can change it by making different choices.

If we follow these guidelines and make sure we tell stories that are concrete, collective, causal, conceivable, and credible, then our communications will be fuller, more systems-oriented, and a lot more likely to build public support, both for direct services and social and policy change. Just as importantly, it will ensure we’re not reinforcing unhelpful attitudes and stereotypes.

However, this research is just a vital first step towards that goal. This is a long-term project and the next stage, which is already underway, involves developing and testing communications tools to help redirect public thinking so that it’s more in line with expert views. These are being co-created with other sector organisations, and together we want to start introducing these evidence-informed communications tools into our working practices.

There was a time not so long ago when it seemed reasonable to suggest that the end of rough sleeping – and in Scotland of homelessness more generally – was in sight. Look further afield and the 2008 national strategy in Finland and the 100,000 homes campaign in the United States offer two powerful examples of what can be achieved when efforts move beyond just a vague ‘war on homelessness’ to a methodical and evidence-driven approach.

These achievements show what is possible, but also highlight what remains to be done. We still have a long way to go and the public’s energy and support will be vital. Reframing homelessness will take effort, attention, and practice, but it will allow us to see the challenge ahead in a new light.

________

Note: The full report on which the above draws can be dowloaded here.

Dr Lígia Teixeira is the Head of Research and Evaluation at Crisis, the national charity for homeless people, and a 2016 Clore Social Fellow.

Dr Lígia Teixeira is the Head of Research and Evaluation at Crisis, the national charity for homeless people, and a 2016 Clore Social Fellow.