England’s top comprehensive schools are often socially selective, writes Carl Cullinane. He outlines the evidence that supports this claim as well as the implications of current policy, and explains what needs to change in order to ensure a fairer admissions process, so that more disadvantaged pupils can access the best schools.

England’s top comprehensive schools are often socially selective, writes Carl Cullinane. He outlines the evidence that supports this claim as well as the implications of current policy, and explains what needs to change in order to ensure a fairer admissions process, so that more disadvantaged pupils can access the best schools.

March saw the arrival of the annual National Offer Day, with around half a million families across England discovering which secondary school their child will be attending from September. As application rates have increased in recent years, this process has become more and more competitive, with many schools, particularly the better ones, increasingly oversubscribed.

While the pressure on places varies by area, in some local authorities anything up to half of children will miss out on their first choice school, with the number of those missing out increasing in most areas. In fact, one in seven schools are at or over capacity, with that figure set to increase given the expected growth in applicant numbers in the near future. So with so many comprehensives oversubscribed, how fair is the process of getting a place?

In 2006, research by the Sutton Trust revealed the extent to which England’s top performing comprehensives, were, in effect, highly socially selective. Disadvantaged children eligible for Free School Meals were significantly under-represented in the 200 schools with the highest attainment, with substantially lower rates than the typical comprehensive, but also lower even than the neighbourhood surrounding the school.

In the context of major changes to the education policy landscape in the intervening 11 years, including a substantial shift from local authority-controlled admissions, to schools managing their own processes via academisation, the Trust’s new Selective Comprehensives 2017 report looks at whether this picture has changed.

This year also sees the school league tables, by which a school’s performance is assessed by parents and education authorities alike, changing significantly. Up until 2016, the headline ranking was based on the proportion of pupils in a school achieving 5 A* to C grades at GCSE, including English and Maths (5A*CEM). This has been replaced by the new Progress 8, which measures how pupils progress across a range of eight subjects in comparison to their ability before entering secondary school. This shift means less of a ‘reward’ for schools taking in pupils with high prior attainment, with potential consequences both for how schools view their intake and how parents’ perceive the best schools.

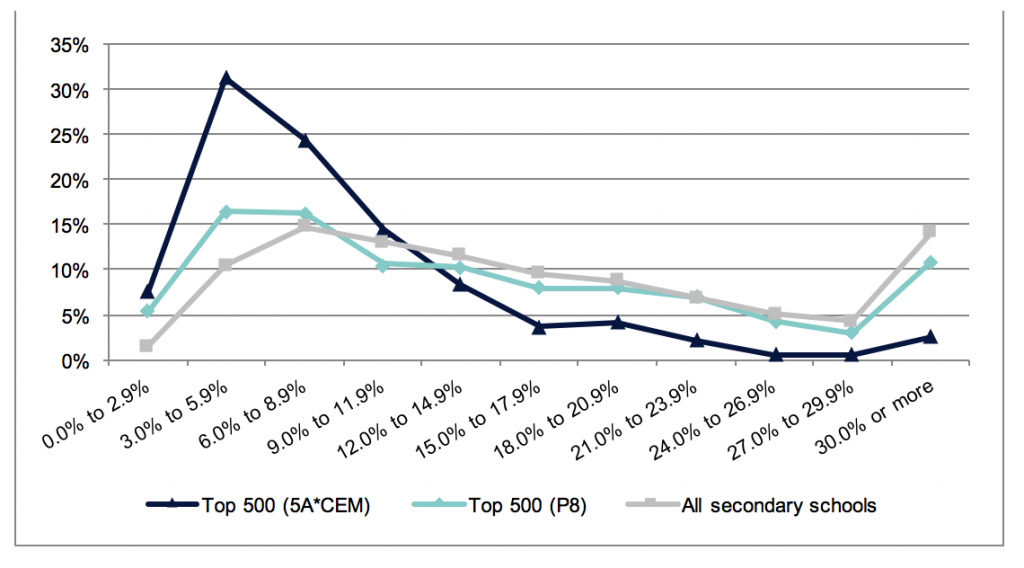

Figure 1. Spread of Free School Meal (FSM) rates across schools

The top performing 500 schools using the traditional 5A*CEM measure continue to be highly socially selective, taking just 9.4 per cent of pupils eligible for Free School Meals (FSM) – just over half the rate of the average comprehensive (17.2 per cent). While roughly half of this gap can be attributed to the location of high attaining schools in catchment areas with lower numbers of disadvantaged pupils, the rest is due to social selection in admissions occurring even within those neighbourhoods. 85 per cent of schools in the top 500 admit fewer FSM pupils than live in their catchment area, with over a quarter having a gap of five percentage points or more, indicating they are substantially unrepresentative of their locality.

The top performing 500 schools using the traditional 5A*CEM measure continue to be highly socially selective, taking just 9.4 per cent of pupils eligible for Free School Meals (FSM) – just over half the rate of the average comprehensive (17.2 per cent). While roughly half of this gap can be attributed to the location of high attaining schools in catchment areas with lower numbers of disadvantaged pupils, the rest is due to social selection in admissions occurring even within those neighbourhoods. 85 per cent of schools in the top 500 admit fewer FSM pupils than live in their catchment area, with over a quarter having a gap of five percentage points or more, indicating they are substantially unrepresentative of their locality.

However, as can be seen in Figure 1, the best 500 schools measured by the Department for Education’s new ‘Progress 8’ measure have FSM rates much closer to the national average (15.2 per cent). They are also less socially selective, with a third of these schools actually admitting more FSM pupils than their catchment area.

These schools are more accessible, have higher intakes of disadvantaged pupils, yet perform strongly for their pupils. Only 270 schools are in the top 500 using both measures, indicating that there is a substantial group of prestigious, high-attaining schools, owing much of their success to a privileged intake with high ability in the first place.

Nonetheless, while a rebalancing of how schools are valued is welcome, there should be no complacency that the problem of social selectivity has been solved. Progress for pupils is highly valuable, but it is absolute levels of attainment that open doors for disadvantaged pupils to university and beyond. So, access to schools that excel in terms of both progress and high achievement is essential, and this group of 270 schools remain very selective, with average gap of 3.5 per cent between the school FSM rate and that of their catchment area.

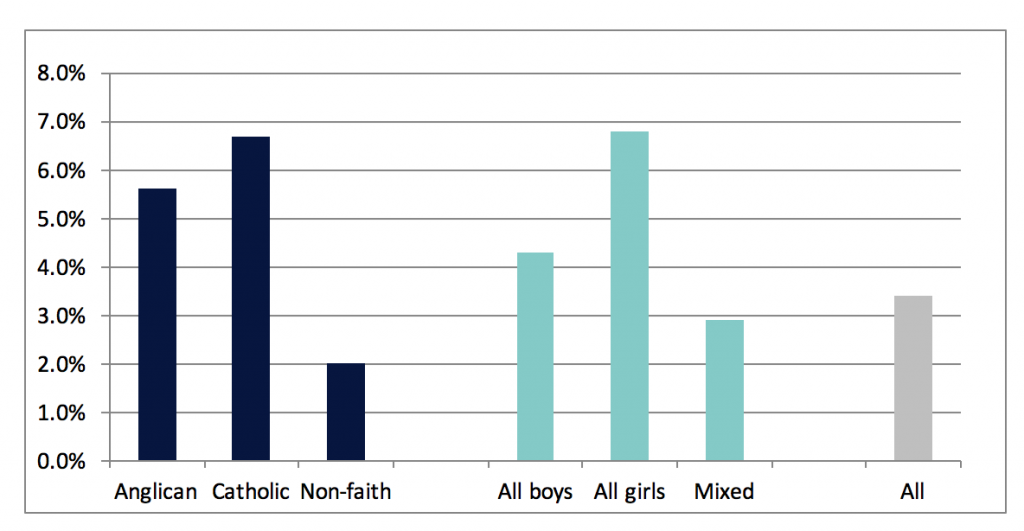

Figure 2. Gap between school FSM rate and catchment area, by school type among top 500 A*CEM schools

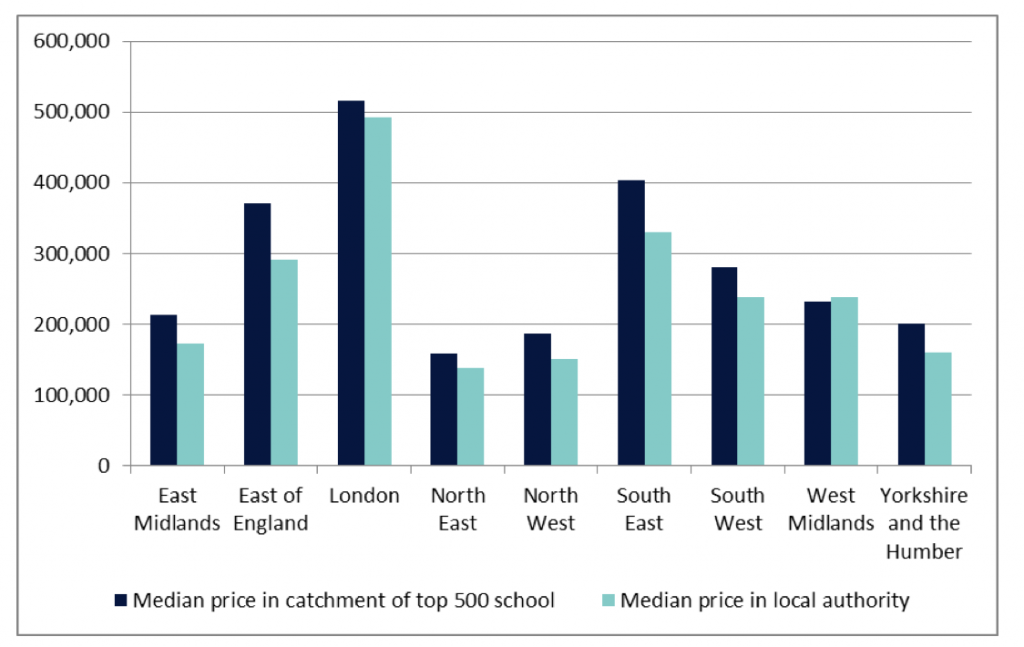

Social selection in a comprehensive system occurs through a variety of mechanisms, including the nuances of complicated school admissions codes, information availability, and parental choice. One of the ways the latter manifests itself is through the property market. Surveys frequently show that parents are willing to move house to live in a particular school’s catchment area, and this is borne out in their behaviour, with our research showing that houses in the catchment areas of top schools generally cost about 20 per cent more than a typical house in the same local authority.

Figure 3. House price differentials in top school catchment areas, by region

House buyers willing and able to pay a substantial premium to live in the catchment area of a top school are likely, over time, to lower the accessibility of the school to those from disadvantaged backgrounds. This undermines the nature of the comprehensive system, and introduces an element of de facto selection based on ability to pay.

Several responses to the Sutton Trust report, including from the Department for Education themselves, have used this as an argument for expanding grammar schools, which ostensibly select based on ability. However, grammars are in fact substantially more socially selective, with Free School Meal rates of around 2.5 per cent, well below that of the best comprehensives. Expanding grammar schools in their current form, without radically overhauling their accessibility to less well-off pupils, would increase rather than reduce barriers to opening up more good school places to children from across the socio-economic spectrum.

Instead, a reduced emphasis on proximity in school admissions would allow fairer access to the best schools and limit socially divisive house buying incentives. The Sutton Trust recommends two methods in particular: ballots, where a proportion of pupils (around half, ideally) are selected randomly; or banding, where applicants are tested and places allocated equally across a range of ability levels. In combination with better information availability and improved transport provision, ballots and banding can be used to ensure a fairer admissions process, enabling more disadvantaged pupils to access the best schools and promoting a genuinely comprehensive system.

____

Note: a version of this article has also been published by the Sutton Trust and draws on this report.

Carl Cullinane is Research and Policy Manager at the Sutton Trust, which he joined in October 2016 as Research Fellow. He previously worked as a statistician in NatCen Social Research and as a researcher in Democratic Audit UK.

Carl Cullinane is Research and Policy Manager at the Sutton Trust, which he joined in October 2016 as Research Fellow. He previously worked as a statistician in NatCen Social Research and as a researcher in Democratic Audit UK.

My understanding of the argument against grammar schools is that although the bright pupils do better the net effect is lower results.

It is noteworthy that in that case opponents of grammar schools are advocating a policy which clearly gives some pupils worse outcomes than an alternative policy. From a labour party aspect it is again noteworthy that the children being given a worse education than the alternative are children whose parents cannot afford private education or to move into the catchment area of good schools. If there was one group of people whom the Labour Party should be ambitious for surely it is these.

Also, comprehensive schools do have selection. Normally some places are reserved for children who excel at music or sport. So our local maths academy selects on music, sports, but not mathematics. Only in the UK would a specialist maths school select on the basis of sport but not maths.

Personally, I’m in favour of some selection in limited cases. I don’t think carpet-bombing with secondary moderns is the way forward, perhaps some more variety.

And for a bit of a hobby horse, quite a lot of disruptive children are often dyslexic, or somewhere on the aspergers spectrum. I might have some schools for those children for whom sitting in class and rote-learning is a traumatic experience and would benefit from a more supportive creative less-exam orientated environment. that would also help the children whose education is being blighted by the same disruptive children.

I don’t disagree with anything here, but to this 55 year-old the busing proposal just looks like back-to-the future. In the 1970s I attended a comprehensive school in a English city with the usual amount of social segregation. Without busing the school would have been pretty homogeneously working-class. So kids from distant posher areas were allocated to the school and given bus passes so that they could travel up to six miles on two buses to get to school. No big deal you might think. On the other hand it meant up to two hours a day travel time from age 11-18 and the parents hated it. Not because of the social mixing (in my city the difference between posh & working class wasn’t very noticeable to the naked eye) but because of the sheer inconvenience for the kids & the parents (all those school meetings you had to get into the car & trek across town to attend after a long days at work). Its not obvious to me that the policy was particularly effective. Mysteriously the comps in the working-class areas didn’t do so well and the comp in the university quarter did fantastically well (I wonder how that happened?). After a while the busing was abandoned and community schools came into vogue. Parents were, at least temporarily, happier and got more involved in their local school, grades increased all round, but the schools in the working class areas still did much worse than the school in the university quarter.

We’ve tried busing and in the limited form it took it doesn’t look like it made much difference to school performance. Of course maybe massive population movements at 8.00am & 3.30pm might be more effective, but don’t you think it might also have some downsides?

Expecting schools to solve social rather than educational problems seems to be an obsession of the English policy classes in a way that it isn’t in other countries. It’s also an obsession that seems to be inoculated from contact with empirical evidence.

The comprehensive system has been a failure it is time that a different and workable system replaced it, there is an argument that it has reduced social mobility which was available under the grammar school system that only was available to people who actually passed the 11 plus no matter their social background.