Ed Miliband has announced that to counter the Conservative party’s financial advantage during the 2015 election campaign Labour will outnumber them in supporters out on the streets engaging with voters – and will benefit accordingly. Is that a sensible strategy? David Cutts, Ed Fieldhouse, Justin Fisher, Ron Johnston and Charles Pattie have done a lot of research into the impact of local campaigns and use data from the 2010 election to assess whether Labour’s strategy will bring the hoped-for benefits.

In launching his party’s campaign for the 2015 election on 5th January, Ed Miliband admitted that Labour would probably be outspent by the Conservatives over the next four months by a ratio of 3:1. His party would counter that by having many more members and supporters on the streets and doorsteps of their target seats over that period, aiming at four million conversations with voters.

But will conversations convince them to vote Labour? On Radio 4’s Today programme the following day, John Braggins, once a Labour election campaign organiser, argued that you change people’s voting attentions by ensuring that they meet the candidates. The more time candidates spend in their constituencies contacting voters the better they perform. The average constituency has some 70,000 voters and no candidates can contact them all personally, so they focus on those likely to vote for them – those on the party’s database of supporters compiled previously plus residents of areas where their supporters are concentrated. If the candidate can’t contact everybody on the lists or in the selected places, local organisers will seek to ensure that a party canvasser does. Their conversations should help convince its supporters to vote for it again – and in some cases to convince those who didn’t vote for it last time to make the change.

The research evidence supports that argument. Our analyses of the 2010 election, using data supplied to us by the individual candidates’ agents, found that the more people canvassing for a party in a constituency – both members and volunteer non-member supporters – the better its performance there. Canvassers having conversations with potential voters apparently wins them over.

Other evidence sustains that. The 2010 British Election Study questioned some 19,000 people at the start of the official campaign in late March-early April. It asked how they voted in 2005, whether any of the parties had contacted them in the preceding months, and how they intended to vote in May. It also asked how the contacts were made: was it by telephone, by a leaflet, by a meeting in the street, by a visit to their doorstep, by email, text, social media or what.

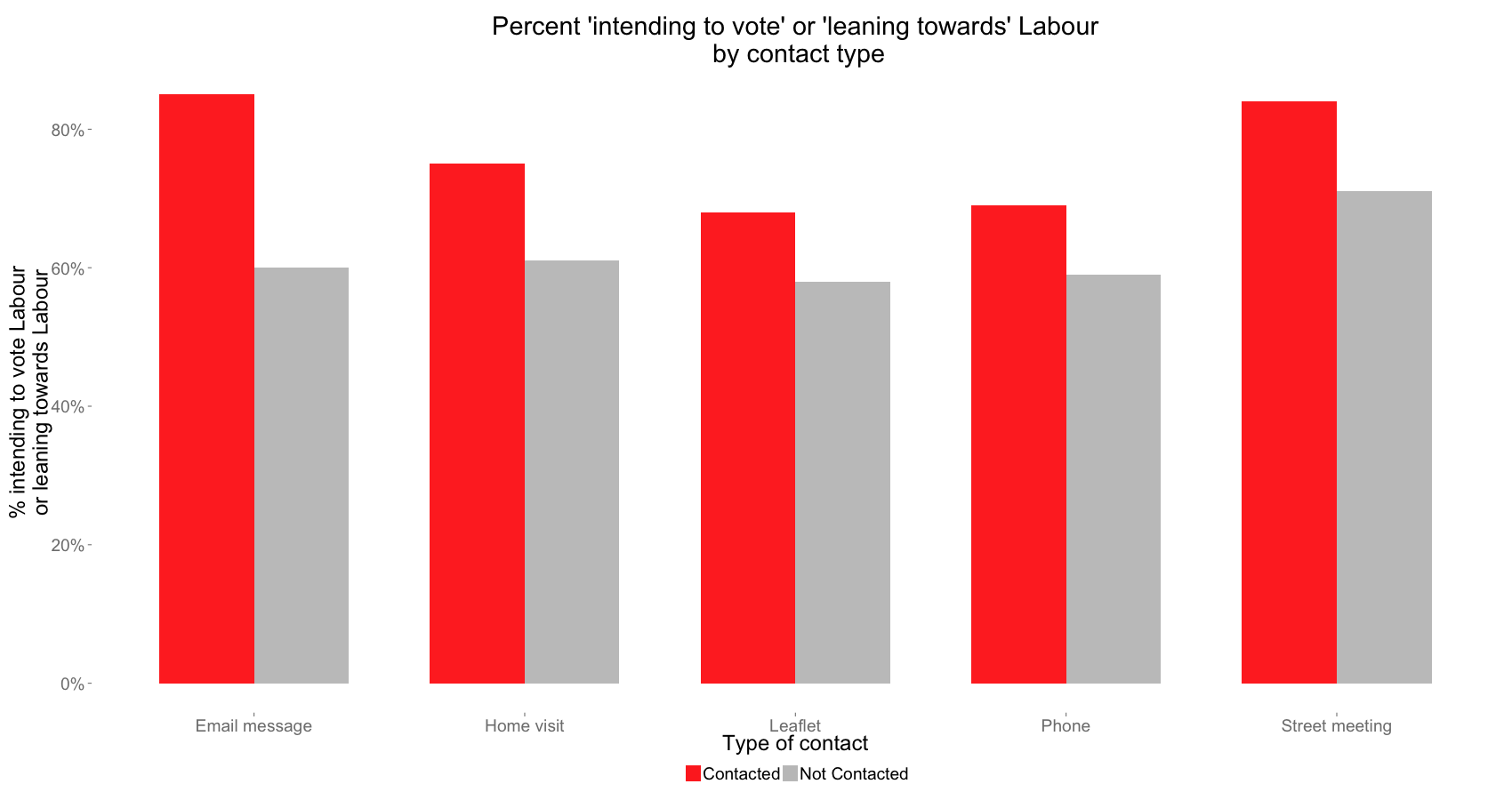

Of that large sample, we look here at the 4,294 who voted Labour in 2005: 2,441 intended voting Labour again, and a further 580 were leaning towards a Labour vote. But, as the first graph shows, those contacted by Labour during the preceding months in one of five ways (very few were contacted by email, text, or social media) were much more likely to intend voting Labour again than those ignored by the party. Labour was losing substantially among its 2005 voters, but was haemorrhaging much more support from those it didn’t contact than from those it did.

Just getting a leaflet increased the percentage intending to vote Labour again from 48 to 57 per cent; 79 per cent of the small number who got an email were going to remain loyal, compared to 48 per cent of those who didn’t; and there was a 15 percentage points difference in loyalty between those who did and didn’t receive a home visit.

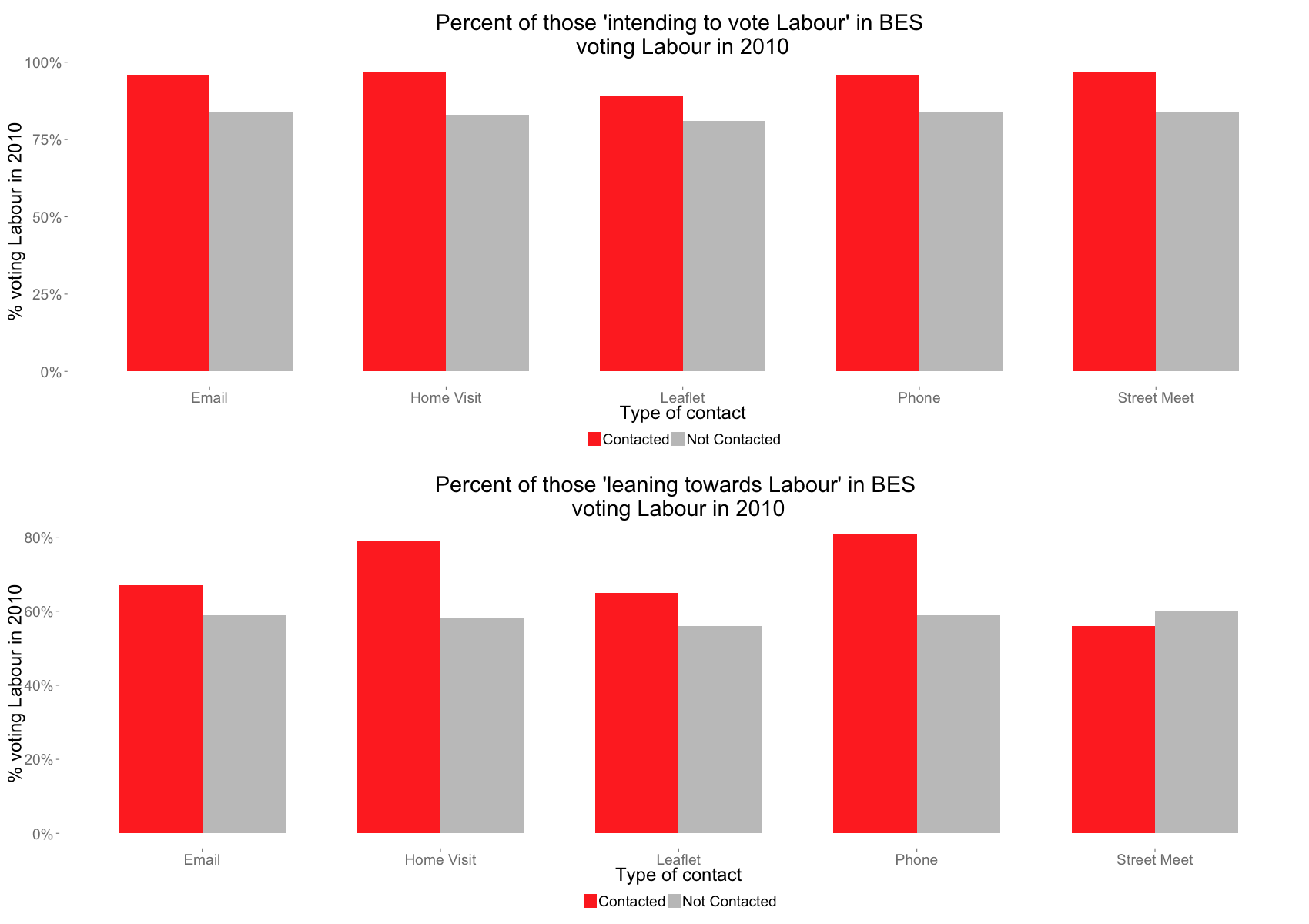

The British Election Study interviewed those individuals again immediately after the election, asking them if they voted, if so how, and whether the parties had been in contact during the last month of the campaign. With those data we can see whether contact with the 2,590 individuals who intended to vote Labour when the campaign started a month earlier, plus a further 640 who were leaning towards a Labour vote (not all of whom voted Labour in 2005), made a difference.

The graphs below clearly shows that it did. Most of those who intended to vote Labour did so, but there was a difference of up to 14 percentage points between those contacted by the party during the campaign and those who were not: 97 per cent of those visited at home voted Labour compared to 83 per cent of those not visited. Labour lost around 16 per cent of those who committed to it in March-April but whom it failed to contact during the heat of the campaign.

Some 40 per cent of those leaning towards Labour changed their mind during the campaign, but many fewer if the party contacted them then. Home visits were especially helpful in shoring up potential support. Only 66 received one, but 79 per cent of them turned out for Labour, compared to 58 per cent who were not visited. Even delivery of a leaflet helped: 65 per cent of those who received one decided that they would vote Labour, as against 56 per cent who didn’t.

We also looked at those undecided who to vote for when the official campaign started. Again, contact mattered: those with whom the party’s candidates and canvassers engaged during the next few weeks were much more likely to vote Labour than those who received no contact. Among the undecided, 40 per cent who received a home visit from Labour voted for its candidate, for example, compared to only 19 per cent of those not visited.

So Ed Miliband’s strategy looks sensible: contacting people between now and the end of March should help ensure that those who voted Labour five years ago commit to the party again. And then contacting those they identify as probable or possible Labour voters during April and early May should ensure they stick with their initial decision – and similarly contact with some of the undecided could convince them to vote Labour too. According to Peter Kellner in that Today discussion on 6th January, around one-third of all voters change their minds during the four months before polling day. Contacting those either committed to or leaning towards Labour, and making them feel that their vote is wanted, will help to ensure that they deliver the support that might propel Ed into Downing Street.

Of course, he will need money too – to pay for the leaflets (even if there aren’t going to be many posters!) and the other costs of running campaigns – but having lots of supporters canvassing votes is crucial. It paid off in 2010 – but, as the graphs here show, Labour didn’t contact that many people. If Peter Kellner is right and some 10 million voters might be open to persuasion between now and 7 May, then if Ed Miliband’s campaigners can engage with 4 million of them this ‘ground war’ may have a telling impact on the final outcome – as, of course, could his opponents’ parallel campaigns.

This article was originally published on the LSE’s General Election blog.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol.

Charles Pattie is Professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield, specialising in electoral geography.

David Cutts is a Reader in Political Science at the University of Bath.

Justin Fisher is Head of Politics, History and the Brunel Law School Department and Professor of Political Science at Brunel University

Justin Fisher is Head of Politics, History and the Brunel Law School Department and Professor of Political Science at Brunel University

Ed Fieldhouse is Professor of Social and Political Science at the University of Manchester

Ed Fieldhouse is Professor of Social and Political Science at the University of Manchester