John Gaffney takes a look at Ed Miliband’s rhetorical approach at the Labour Party conference, writing that The challenge now is to reorientate the party – through his performance – towards an election winning set of policies that will keep the party united behind him and reflect him as possessing a Prime Minister’s ‘character’.

John Gaffney takes a look at Ed Miliband’s rhetorical approach at the Labour Party conference, writing that The challenge now is to reorientate the party – through his performance – towards an election winning set of policies that will keep the party united behind him and reflect him as possessing a Prime Minister’s ‘character’.

Nearly all the editorial coverage of Ed Miliband’s speech to the Labour Party conference on Tuesday, September 23rd in Manchester concentrated on whether it was a good speech, whether he was convincing, who was his targeted audience, and what were the policies he was proposing. To properly understand what is happening we need to see these four aspects as an integrated whole. In fact, the Manchester speech is an excellent illustration of how these elements interact.

From 2010, when Miliband took the party leadership, a series of party narratives emerged to create the One Nation narrative of 2012 (Manchester speech – mentioned 46 times) and 2013 (Brighton – mentioned 6 times). This was the narrative endorsed by the party members and activists, and Miliband became the author of that narrative. He became its author by personalising the narrative – hence all the references over the years to his childhood, his father, his schooling, the Grahams, Zeonoras, and Josephines he has met, and so on.

As regards the party, it has worked extremely well. Few party leaders in Labour’s history have been less divisive. And the responses in the hall to his speeches, certainly since 2012, have been significantly warmer than we are led to believe by the media commentators. The personalising of the party’s narrative makes his character as well as the ‘trivial’ extremely important – his likeability, his intelligence, his policy-wonk background and – potentially dangerous – the victory over his brother, The Sun photo op, the cartoons, and the bacon sandwich. These things are important, in the first instance, not as regards whether he is prime ministerial – that comes later – but because he is the party’s voice; he rhetorically ‘performs’ the party.

The challenge now is to reorientate the party – through his performance – towards an election winning set of policies that will keep the party united behind him and reflect him as possessing a Prime Minister’s ‘character’. In narrative terms, he has to bring back into the mainstream the discourse and ideas of other Labour narratives, social democracy, the Third Way, 1945 statism, trade unionism, green politics, and blend them with the prevailing narrative. And the use of ‘together’ (used 44 times) is the rhetorical link between One Nation (not mentioned at all) and the other ‘returning’ narratives. The policy proposals (and some of them – bank reform, apprenticeship scheme – were trailed in earlier One Nation conference speeches) – on energy, housing, the minimum wage, bank reform, apprenticeships, decentralisation, and especially the NHS – should be seen in this light: they appeal to most of the strands of thinking in the party.

This narrative reorientation has not been that smooth over the last year with some refusing to endorse One Nation and some feeling it was being abandoned. One of the elements central to both the narratives now being blended and the personalisation of the party’s voice is the use of high emotion. This is the reason for the central rhetorical role of the NHS at this conference, as was seen in the reactions to 91-year old Harry Leslie Smith’s speech. It also is a key element in all of Labour’s narratives, which actually share much more than they do not. Hence too, perhaps, the unconscious lapsus by Miliband in forgetting two sections of his memorised speech, on the deficit and immigration, which although emotional issues are more divisive. Polls show (in fact, alongside jobs and the immigration he forgot to talk about) that the NHS is also one of the greatest concerns of – and most treasured insitutions for – the British public. Here, and in his general rhetorical approach at Manchester (more downbeat, reflective etc.) he was, against what many commentators said, talking to both the party and the public.

In fact, through the topics chosen, the references to the people he had met, jokes which acknowledged the media depictions of him, and so on, he was talking to the party but also to a much wider public. ‘Country’ and ‘people’ were, moreover, the most prominent words. He also looked twice directly into the camera in front of him which at home would be experienced as a direct address. The next months of course will be decisive, but the future success of the Labour Party in May 2015 is not simply dependent upon promoting good and persuasive policies, it is to do that as a set of manifesto commitments which grow out of the evolving party narrative of the last five years.

Even more importantly, it must reflect the views and aspects of the character of the party leader. The way in which Miliband ‘performs’ the elaboration of detailed policy – for Manchester 2014 was less a post-2015 policy offer than a reorientation – and the elements of the manifesto are key to his overcoming the continuing public confusion about what he stands for, who, in fact, he ‘is’. All of the policies must be aspects of his character, first because he is the voice of the party’s narrative, and second because strong Prime Ministers have strong policies.

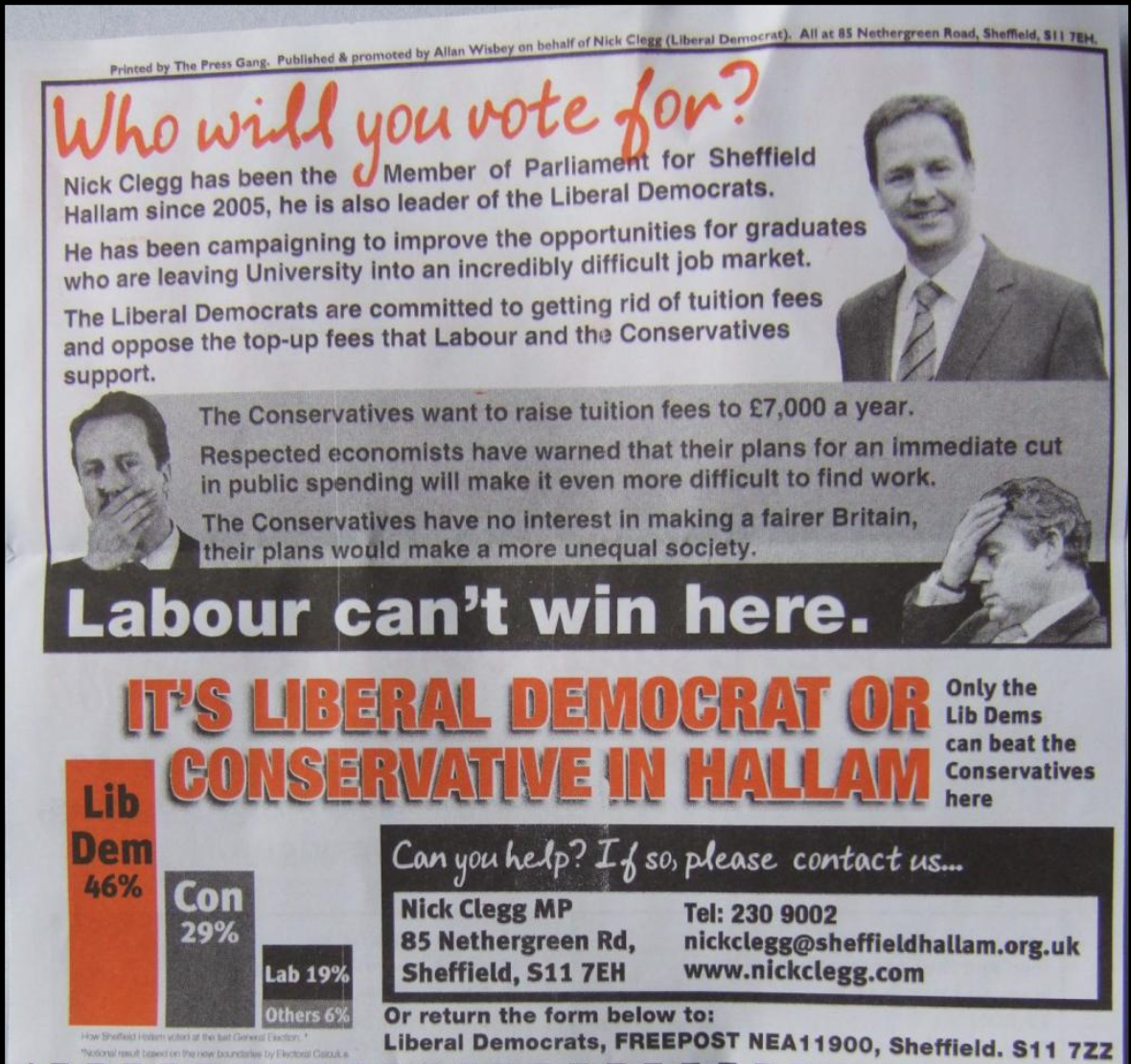

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Homepage image credit:

John Gaffney is Professor of Politics at Aston University, and Co-director of the Aston Centre for Europe. He and Amarjit Lahel have recently published on Miliband and the Labour Party in both Government and Opposition and The Political Quarterly. His three most recent books are The Presidents of the French Fifth Republic (with David Bell, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), Political Leadership in France (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), and Celebrity and Stardom in Postwar France (with Diana Holmes, Oxford: Berghahn, 2011). He is currently a Visiting Professor at Sciences-Po, Rennes, and is running a Leverhulme project on political leadership in the UK.

John Gaffney is Professor of Politics at Aston University, and Co-director of the Aston Centre for Europe. He and Amarjit Lahel have recently published on Miliband and the Labour Party in both Government and Opposition and The Political Quarterly. His three most recent books are The Presidents of the French Fifth Republic (with David Bell, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), Political Leadership in France (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), and Celebrity and Stardom in Postwar France (with Diana Holmes, Oxford: Berghahn, 2011). He is currently a Visiting Professor at Sciences-Po, Rennes, and is running a Leverhulme project on political leadership in the UK.