Sara Seims lays out three rules that, if followed, may well improve the delivery of family planning initiatives to the developing world. These entail: a careful weighing of the costs and benefits of various options; the formulation of a specific and sophisticated measurement target; and a reaffirmation of donors’ values and philosophies.

Sara Seims lays out three rules that, if followed, may well improve the delivery of family planning initiatives to the developing world. These entail: a careful weighing of the costs and benefits of various options; the formulation of a specific and sophisticated measurement target; and a reaffirmation of donors’ values and philosophies.

On July 11, the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), in partnership with the Gates Foundation, will launch a multi-year effort that they hope will lead to 120 million new contraceptive users in the 69 poorest countries in the developing world by 2020—an increase of approximately 50 per cent from the current number of 260 million contraceptive users in these countries. In order to avoid the landmines stepped on over the years in such initiatives, this article recommends three simple rules for DFID to follow.

Just to provide a little context, DFID is a generous supporter of international family planning. For example, in 2010 the UK provided almost £20 million to the United Nations Population Fund and over £11 million to the International Planned Parenthood Federation. In its official documents, DFID usually discusses family planning within the broad context of helping to protect the health of the poorest and most vulnerable women. There is little direct mention of reproductive rights but frequent mention of helping women have real life choices.

Rule One: Be Careful What You Measure!

Do not set goals whose apparent simplicity might appeal to political leaders and heads of donor agencies but which are likely unachievable and perhaps even misdirected. The development aid landscape is unfortunately littered with initiatives launched with great expectations and political buy-in that eventually fizzled out. One such example is Health For All by the Year 2000, launched by the World Health Assembly in 1979 and clearly not achieved by any stretch of anyone’s imagination. Another is the World Health Organization and UNAIDS’ 2003 launch of the catchy 3 x 5 campaign which aimed to provide antiretroviral drugs to three million additional people living with HIV/AIDS within five years. An evaluation by the Canadian aid agency concluded that only about 40 per cent of this goal was achieved. Critics of development aid seize on such experiences to stoke skepticism and cynicism.

The FP Summit initiative is expected to need an additional US$4.3 billion in total from now to 2020, of which $2.3 billion will come from donors and the rest from the governments of those 69 countries. As of this writing, it is not clear how the estimated $2.3 billion of new donor money that DFID and Gates hope to raise will be spent, but the documents thus far made available indicate that the overwhelming bulk of the money will go to contraceptives and expanded family planning services. The initiative particularly wants to target 120 million of the approximately 220 million women in these countries who are having sex and don’t want to be pregnant right away (or ever again) but are not using contraception. These women have been identified as having an “unmet need” for family planning. I believe that this goal should be modified because the evidence is clear that the majority of unmet need is due to concern about side-effects and the inconvenience of some contraceptive methods, as well as social and cultural opposition to use.

In the poorest countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, there are very high discontinuation rates, usually for these reasons, among women who have at one time or another elected to use contraception. A better strategy would be to help women who are currently using contraceptives to use them for longer periods of time since will have more impact on reducing unwanted pregnancies than efforts aimed primarily at getting new contraceptive users.

I recognise it is easier to sell an idea that sounds expansionary rather than one which focuses on doing better what you are already doing, but the FP Summit should nevertheless shift its focus to the latter if it wants to maximise help to women.

Rule 2: Don’t rush to spend the money before examining the pros and cons of various options.

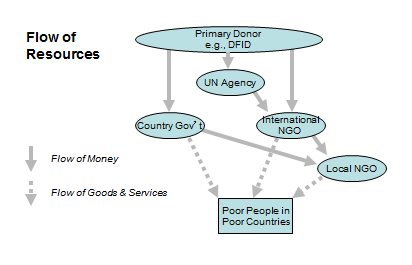

Donor agencies, being chronically understaffed— DFID is no exception—have been tending globally to make a smaller numbers of larger grants, to reduce their own administrative workload. As part of this shift, DFID and other donors may make large grants, usually to UN agencies who may then re-grant those funds to other organizations. The costs of effective management (and its benefits) are thus shifted from the donor agency to the entities receiving the money. When these funds are re-granted through complicated UN systems, there can be delays in the organizations receiving the funds and they can also become tied up with the bureaucratic red tape of the UN Agency concerned. For these non-government organizations, vital players in the culturally sensitive area of family planning, this complexity (see the visual portraying the flow of money, goods and services) too often leads to administrative delays and inefficiencies while priorities and policies get muddied in the various bureaucratic layers. DFID should thoroughly examine all funding options and carefully monitor the ones it selects to make sure that they operate as smoothly as possible and, more importantly, work effectively in aid of strategic intent.

Rule 3: Donors should reaffirm their values and philosophies when working in partnership with constituents who do not necessarily share these 100 per cent.

In the specific example of the FP Summit, a significant portion of civil society organizations working in the reproductive health field have been concerned that the DFID/Gates initiative excludes vital areas of reproductive rights such as safe abortion and has downplayed the need for complementary investments in improving the role and status of women and girls. DFID has a fine track record in all of these areas and should take advantage of the FP Summit to reaffirm their values and policies.

DFID has a strong and well-deserved reputation for being one of the best and most thoughtful aid agencies. With regard to helping women and girls in developing countries live better lives, I cannot think of another aid agency with a better track record and with more determination to measure the impact of its work. I am therefore hopeful and optimistic that the FP Summit and the roll-out of the initiative will reflect DFID’s usual high standards of performance, if the above three rules are followed.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Sara Seims is a Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics and a Senior Advisor to the Packard Foundation. She is based in London where she is analyzing the development assistance policies and practices of the major European donors in the area of sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).