Differences between the messages communicated by the two main parties through Twitter during the election campaign were consistent with differences between left and right wing moral priorities observed elsewhere, write David Smith and Beatrice Baroni. They use the Five Foundations theory to explain their findings.

Differences between the messages communicated by the two main parties through Twitter during the election campaign were consistent with differences between left and right wing moral priorities observed elsewhere, write David Smith and Beatrice Baroni. They use the Five Foundations theory to explain their findings.

We all know the clichés: Corbynistas are well meaning fantasists, short of a magic money tree, and the Tories are “the nasty party”. Yet these stereotypes of Conservative voters patronizingly sympathising with Labour ones, who can’t understand how they sleep at night, may reflect something deep rooted in our senses of right and wrong.

To explain disagreements in our moral makeup, psychologist Jonathan Haidt devised the Five Foundations theory. This model is based upon extensive reviews of psychology, anthropology, and philosophy and argues that each of us has an intuitive moral sense comprising five elements.

The five moral foundations

The first foundation is care for others: a human desire to help vulnerable groups such as children or the elderly. Next comes fairness – our sense of justice and autonomy. This concept is separately defined to address concerns about inequality, or matching proportionality of effort to reward i.e. our tax debate in a nutshell. The third is loyalty towards in-groups, which can manifest in nationalist/patriotic sentiments or allegiance. Researchers have suggested this was a key aspect to the Brexit victory. Fourth is authority, typified by recognising leaders, reverence to hierarchies or preserving tradition. Fifth is purity, which is commonly linked with religion or a fear of degradation. A sixth moral sense, of liberty, has been proposed although is, as of yet, not canon.

Different cultures are thus defined in terms of the narratives and constructs they build around each of these foundation. For instance, UK leaders talk about “freedom, tolerance of others, and accepting responsibility” as British values, although they “don’t do God”. However, obviously significant variation can also exist within a culture.

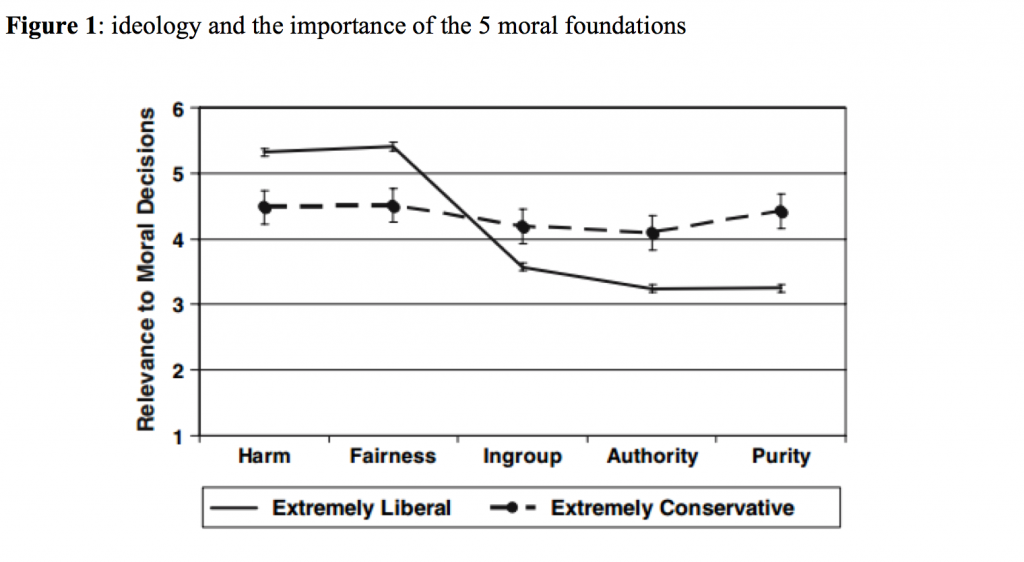

Taken from Haidt & Graham (2007)

Taken from Haidt & Graham (2007)

For example, Haidt theorizes that differences between liberals and conservatives show down to differences in moral foundation priorities. In a paper he co-authored, it was observed across four studies that liberals were more concerned with issues relating to harm and fairness vs the other three. In contrast, conservatives cared less about these two but were generally concerned about all five similarly, suggesting a wider moral palate. This, Haidt argues, can advantage conservatives who are historically better able to inspire confidence when addressing nationalism, tradition and religious freedom.

The same lab team also showed left wingers find it harder to understand the motivations of conservatives than the other way around. They argue this happens because both groups value care and fairness, although conservatives rely more on the three other foundations. In the UK this was illustrated in pre-election polling that saw more Labour than Conservative voters say the NHS was the most important issue for them (42% vs 11%) and vice versa for leaving the European Union (39% vs 11%).

Getting the message across: Twitter and the five moral foundations

In the modern age social media plays a considerable role in electoral campaigning. Sites such as Facebook and Twitter allow voters a way to share grievances, candidates a platform to communicate with constituents, and political parties a means to share their values. It is this last point that we were interested in exploring. In particular, we wondered if differences between the Conservative and Labour Twitter feeds were in line with the liberal vs conservative divisions identified by Haidt and his team.

We chose to use Twitter instead of Facebook because its more instantaneous format necessitates that parties post a lot. Furthermore, since users are more likely to share content then people do not need to follow parties to hear from them. We monitored their account activity for a week, from 26 May until 2 June 2017. This period followed the publication of both party manifestos, and a temporary campaigning gap in tribute to victims of the Manchester bombing. It was also a time when both accounts would be especially busy, since it encompassed both the Channel 4 interviews with Jeremy Paxman, the seven-way debate and the BBC Leaders Question Time.

Their tendency to attract younger voters may lead people to assume the Labour account would tweet more often, since this group uses social media more. Yet in the week we looked at, their 229 tweets were dwarfed by the Conservatives’ 742. This may be because the Tory account was compensating for the generational gap in users. Their team would therefore need to work harder to communicate party values, in the face of many more tweets elsewhere about Labour (40% vs 26% of tweets with election-related hashtags).

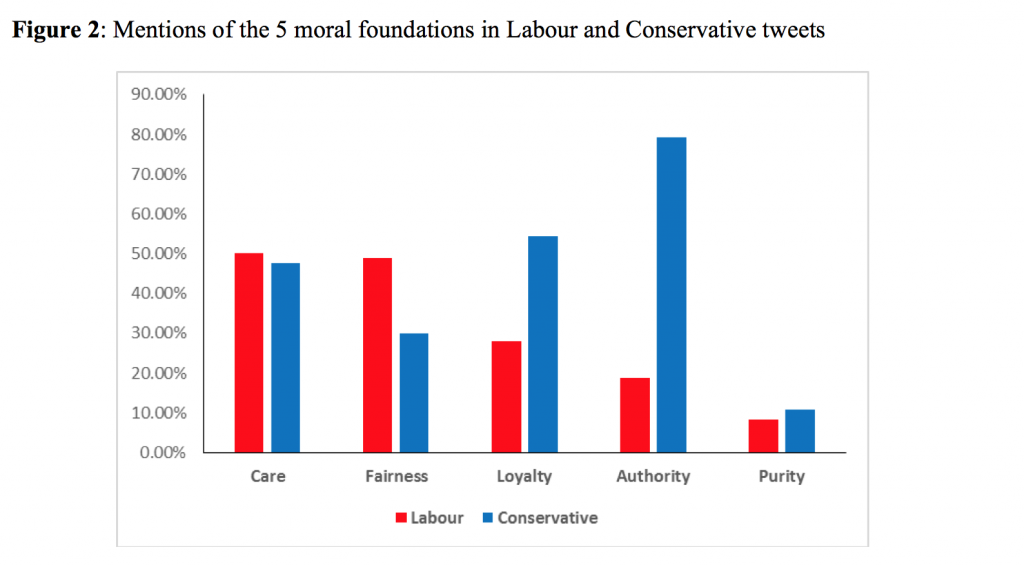

The emphasis on each foundation was calculated as a percentage of the overall total, with some tweets relating to all or none of the five. Examples of care tweets emphasised protecting families, investing in public services or increasing national security. Fairness was reflected in tweets about sticking up for ‘the many not the few’, or allowing people to take home more of their wages. Loyalty was commonly evoked by strengthening the country through Brexit or appeals for direct involvement. Authority was usually associated with recognising and/or trusting in the party leadership. And the few instances alluding to purity cited moral corruption, democracy as the most important thing or relationships with religious establishments (e.g. accusations of Jeremy Corbyn being an anti-semite or supporting terrorism).

The findings are in line with what Haidt anticipates. The Labour account tweeted marginally more about care (50% vs 48%) and a lot more fairness (49% vs 30%). Whereas the Conservative feed featured far more references to loyalty (54% vs 28%) plus authority (78% vs 19%). Note that both foundations were even alluded to in the party moto: “strong and stable leadership in the national interest”. And although neither profile posted often about purity, this was also a more frequent topic on the Tory one (11% vs 8%).

Many of the tweets were negatively phrased. In particular, the Conservatives regularly questioned Labour figurehead’s competence or intensions as a means to advertise May’s virtues. This was true about both sides, although overall the Labour account was predominantly positive (80% vs 28%) while the Conservative one was more negative (54% vs 48%). Many messages were both e.g. “PM – back of the net every time – JC – a series of tragic own goals”.

Given the unexpected result it would be imprudent to say that the above, along with the wider campaign, reflects Haidt’s “conservative advantage”. However, since then commentators on both sides have suggested that Theresa May was not a suitable candidate for such a campaign. As per the Twitter page, the wider campaign was very personal. For instance, it was not uncommon for the Conservative party to call itself ‘Theresa May and her team’. An example of this presidential approach backfiring was when voters condemned May for not taking part in TV debates. This decision may have undermined the ‘authority’ foundation by subverting an impression of her as a strong leader, and her opponent as weak. Furthermore, perhaps those who would not normally vote for a left wing candidate were impressed with Jeremy Corbyn’s perceived honesty. The Conservative’s controversial social care policy has also been proposed as a deciding factor in the campaign splitting voters. With its nickname “the dementia tax”, it was framed in clear violation of the care foundation.

So it would appear divisions between the two major parties’ Twitter feeds are consistent with differences between left and right wing priorities observed elsewhere. Of course, if these trends reflect campaigns responding to voters’ priorities, are part of an effort to shape them, or both, is open to interpretation. Nonetheless, their online presence further shows that the moral mindsets of left and right wing voters reflect different moral priorities, rather than one group being more righteous. It is also a reminder that when we assume somebody is delusional or a monster it’s normally not that simple.

_______

David S. Smith is Lecturer in psychology at BPP University.

David S. Smith is Lecturer in psychology at BPP University.

Beatrice Baroni is a research intern and psychology student at BPP University.

Beatrice Baroni is a research intern and psychology student at BPP University.