Claire Annesley and Francesca Gains show that government attention for gender equality issues is higher when economic indicators are positive. In tough economic times, not only do women bear a heavier burden, but policies to close the gender gap are generally off the agenda – unless external pressure can be applied.

Claire Annesley and Francesca Gains show that government attention for gender equality issues is higher when economic indicators are positive. In tough economic times, not only do women bear a heavier burden, but policies to close the gender gap are generally off the agenda – unless external pressure can be applied.

Yesterday’s Queen’s Speech announced the coalition government’s intention to ‘make parental leave more flexible so both parents may share parenting responsibilities and balance work and family commitments’. This is very welcome news. Ever since the recession hit the UK, analysis has consistently shown that progress towards gender equality is being undone. Female unemployment is at a record high, women are bearing the brunt of cuts in benefit, and the government is failing to meet its legal duties to assess the potential gender impact of its policies.

Our research, published in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations, suggests that weak economic performance and recession closes down the space for further progress on gender equality. The only exception – and this includes the parental leave announcement yesterday – is when there is a legal or institutional requirement to promote gender equality from outside Government.

We investigated when policies to promote gender equality managed to capture government attention. After all, governments have a core set of issues to attend to and little space for new demands. Our hunch was that gender equality policies that have costly or redistributive consequences – those which encourage women into the labour market and men to take on more of the unpaid caring roles – would struggle to get on the agenda when the economy was not performing well. Elite advocates in government have to bring forward and make arguments with an acute awareness of the economic climate. Our expectation was that advocacy for policy issues which carry economic consequences would be easier when the economy is growing, unemployment is low or there are low levels of public anxiety about the economy.

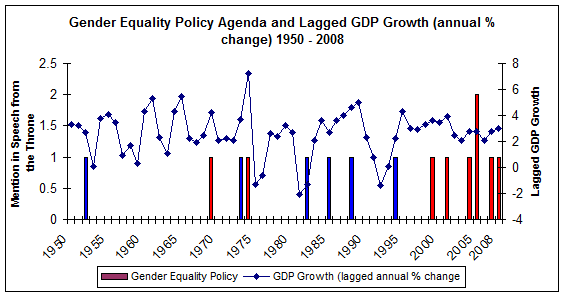

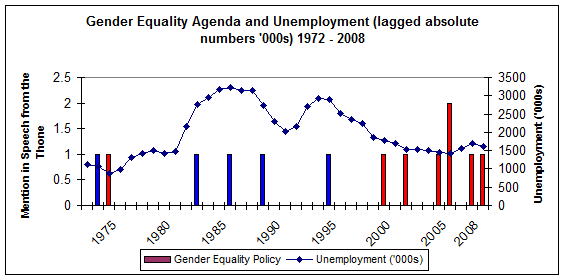

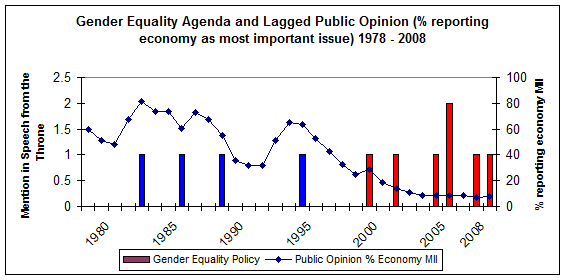

Using data from the UK Policy Agendas research we identified the years when issues such as equal pay, family leave and pension equalisation policies were mentioned in the Queen’s Speech. This denotes that the government of the day is giving these policy demands serious attention. In the post-war period we identified 15 Queen’s Speeches when these types of policy got a mention (shown in figures 1 -3 with blue bars representing policy mentions by Conservative Governments and red lines by Labour Governments). They included an early amendment to maternity provision in the 1950s, the equal pay and anti-discrimination legislation following second wave feminism in the 1970s, policy responses to legal challenges arising from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the 1980s, and New Labour feminists’ advocacy for gender equality by ‘the most feminist and family friendly government in British history’.

Figure 1 shows a trend line for GDP growth (annual percentage change) lagged by a year to show the kind of economic information informing elite appreciative systems at the time of each Queen’s Speech. Figure 1 shows, with the exception of two years, that advocacy for costly gender equality policies came at times immediately following GDP growth and that there was a higher average mean score for lagged economic growth during the years with gender policy mentions compared to years with no gender equality mentions. The gaps in the occurrence of gender equality policy mentions in the Queen’s Speeches occurred at the end of the 1970s and early 1990s, coinciding with poor and falling GDP. The two years which do not follow this overall pattern are 1955 and 1985 where policy mentions related to legal challenges the timing of which we suggest transcended economic considerations.

Figure 2 shows data for the level of unemployment and this relationship with space on the government agenda for gender equality policy mentions. This shows that gender equality policy mentions in the 1970s, 1988 and the Blair administrations take place during a period of falling unemployment. Three policy mentions – in 1982, 1985 and 1994 (during Conservative administrations) – do come at times of rising unemployment, but these agendas are responding to challenges from the ECJ. And, overall, the average unemployment rates for years that precede a gender equality policy mention are lower than for years when no gender equality policy is included in the Queen’s speech.

In figure 3 we show data on public confidence in the economy using Ipsos MORI data, showing percentage of survey respondents citing the economy as the most important issue, as an indicator of the public’s confidence in the economy. Again, except for two years -1982 and 1994 – policy mentions come at times of falling or low public concern about the economy.

So, overall, it seems that securing government attention for gender equality issues is easier for elite advocates when the economy is performing well, unemployment is low and public confidence in the economy is high. Costly gender equality policies do get a mention when the economy is not performing well, but only in response to legal or institutional challenges, most recently by the EU. Yesterday’s announcement in the Queen’s Speech to reform parental leave follows a similar pattern; the Coalition appears to be responding to the revised European Framework Agreement on parental leave which entitles men and women workers to an individual right to leave when a child is born or adopted.

What does this all mean for gender equality policy in the current economic climate? Firstly, we argue there is a ‘double whammy’ in achieving gender equality. Not only are women bearing the brunt of the costs of recession, but from the research we report here, we would anticipate that there is little space for positive gender equality advocacy within the Coalition Government until the economy picks up. However, our research also shows that is not impossible to get gender equality issues onto the Queen’s Speech. Even when the economic outlook is poor, governments have had to give their attention to legal challenges or institutional requirements. For advocates for gender equality this analysis points to a strategy to identify and pursue legal and institutional challenges wherever they arise, in order to sustain government attention to gender equality – even when times are hard.

See: Annesley, C. and Gains, F. (2012) ‘Investigating the Economic Determinants of the UK Gender Equality Policy Agenda’ British Journal of Politics and International Relations, currently available on Early View.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Claire Annesley is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester. Claire is a member of the European Commission’s network of experts in the fields of gender equality, social inclusion, health and long-term care (EGGSI) and is on the Management Committee of the UK Women’s Budget Group

Francesca Gains is a Professor of Public Policy in the School of Social Sciences, Postgraduate Director for Politics and a Senior Research Fellow of Institute for Political and Economic Governance at the University of Manchester.

2 Comments