In previous posts we have highlighted how pension systems must be adapted to the fact that we are living longer, and one of the most common recommendations is to incentivise people to save in personal private pensions. Leandro Carrera investigates how high fees in pension plans can significantly reduce final pensions, and what the UK can learn from other European countries’ pension schemes.

In previous posts we have highlighted how pension systems must be adapted to the fact that we are living longer, and one of the most common recommendations is to incentivise people to save in personal private pensions. Leandro Carrera investigates how high fees in pension plans can significantly reduce final pensions, and what the UK can learn from other European countries’ pension schemes.

In October, the BBC’s Panorama highlighted how high fees among UK individual pension plans may significantly decrease workers’ pension pots, leading to future pension benefits that will not be enough to cover their basic needs once retired. These fees may represent up to 80 per cent of the total money paid into a fund. While the specific assumptions of the Panorama analysis have been criticised, there is agreement among experts that management fees may, in some cases, reduce a person’s total pension pot in a significant way.

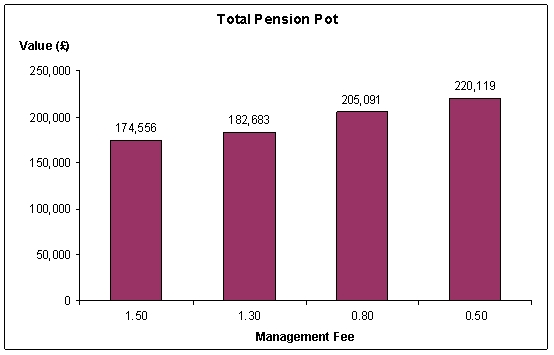

Management fees among pension providers in the UK vary significantly from around 0.8 per cent to 1.5 percent or more of a person’s total accumulated assets. These figures may seem low, but as a fund grows over time, they may represent a significant share of it. In fact, a report from the Royal Society of Arts has highlighted that a 1.5 per cent management fee can reduce the total pension pot of someone contributing £1,000 per year during 40 years from £250,000 (before fees) to £174,000, or 30 per cent; assuming a hypothetical return of 6 per cent per annum. Using the same assumptions, the graph below shows the total pension pot for management fees of 1.3, 0.8 and 0.5 percent. The differences are worth noting:

To understand why management fees can be so high, we must consider that when workers go to the market to “shop” for a pension plan, retail pension providers will charge a management fee that includes not only the cost of actually investing his or her contributions but also includes the costs of setting the account for the first time, providing information at the moment of opening the account and also over time, other marketing costs, database maintenance, etc. In fact, the aforementioned report has estimated that only 0.2 points a typical 1.3 percentage points management fee corresponds to the cost of investing participants’ money.

The report and a significant body of academic research have highlighted that reduced management fees can be obtained from economies of scale in administration; for example, through employer-sponsored group pension plans. These are plans set up by grouping all the individual pension plans from workers from a given company and run together by a pension provider chosen by the employer. Because the pension provider is dealing with a bulk of individual plans at the same time, it will often be able to offer a reduced management fee. Still, even in this case, pension providers will be managing a somewhat reduced universe of individual plans and they will still be responsible for managing their own database, checking that contributions and payments are made every month, providing information to participants, etc. All these extra costs will be added to the true cost of investing participants’ money and they will be reflected in the total fee charged.

We can look at two close examples in Europe that are able to provide decent returns and low fees thanks to covering a wider range of participants. In the Netherlands, a system of industry-wide private funds covers every single worker. Because of their wide coverage, these funds are able to charge low management fees.

The Swedish system of private accounts also ensures low management fees. Here, a centralized authority is in charge of collecting contributions from participants, investing them in different funds and maintaining a central database to check that contributions are made. This centralized structure ensures that pension funds charge a fee only for investing people’s money.

Personal accounts in Sweden:

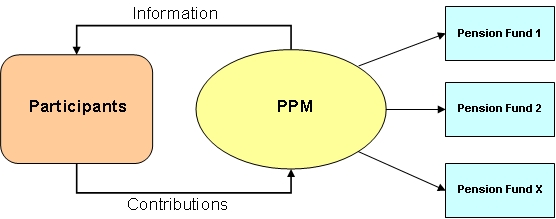

After years of debate, in 1999 Sweden introduced a system of mandatory personal accounts. A new government pension agency, the PPM (Premiepensionsmyndigheten), was established to administer the plan and act as a clearinghouse. The clearinghouse model was chosen to keep administrative costs down by drawing on economies of scale in administration. The PPM then invests workers’ contributions in up to five funds of their choice. At the moment, there are more than 600 registered funds that offer different combinations of investment vehicles (shares, bonds, etc) to respond to customers’ preference for returns and risk. There is also a default fund for those that decide not to make an active investment decision. The figure below depicts the structure of the system.

Central to understand why the system is able to provide low fees is the fact that the PPM is the single body in charge of collecting contributions, informing participants about the characteristics of each fund, submitting statements to participants about their contributions and their performance in the funds they choose, and also processing changes among funds, which can be requested at anytime even by email. In this context, the fee charged by fund managers is also relatively low as it only involves the costs of investing participants’ contributions. To illustrate this point, in 2003, the average fund fee was 0.43 per cent of assets and the PPM fee as 0.3 per cent. Thus, the total average fee charged was 0.73 per cent. Over the years, the system has been able to achieve more efficiency and both the PPM and average fund managers fees have been reduced. Thus, according to some estimates, by 2007 the PPM fee had fallen to 0.12 per cent and the average fund fee was 0.33 per cent, leading to a total average fee of 0.45 per cent of assets. The same study estimated the total average fee by 2020 in around 0.22 per cent of assets.

The Swedish centralized approach to private pension saving, which still provides choice for participants, has led to more efficiency in the system resulting in lower fees over time. Can this be applied to the UK? The 2005 Pension Commission report examined the problem of high cost in private pensions, especially for those in low incomes, and proposed a system of low cost personal accounts, the National Employment Savings Trust (NEST), which should be fully implemented by 2012.

The UK approach: NEST

Although the specific implementation of NEST is still under way, the structure proposed in the 2005 Pension Commission report and subsequent DWP publications, contemplates a central investment board that will be in charge of collecting contributions and investing them in the funds selected by the participants. Yet, there are significant differences with the Swedish case. Enrolment will be automatic only for those who are not currently offered an occupational pension by their employer and earn between £5,000 and £33,000 a year. In addition, the maximum amount that any participant can contribute to the system is limited to £3,600 per year. While this amount is not insignificant, the expert opinion is that it may lead to an inadequate pension benefit for those with above average incomes. Therefore, those close to the upper earning limit may be better off by opting out of the scheme.

In terms of the cost of the system, the Pension Commission original intention was to achieve a total management fee of 0.3 per cent of assets. However, already in 2006, DWP observed that the costs would be higher at the beginning of the system due to implementation costs, and it proposed to charge a 2 per cent fee on contributions during the initial years of the scheme (although it has not specified exactly for how long). This will take the actual management fee to 0.5 per cent of assets. Experts have already warned that these high initial set up costs will have a negative impact and penalise early joiners to the scheme. This may increase the probability of people with above average earnings, to opt out of the system.

In sum, while the proposal of setting up a low cost system of personal accounts may be well intentioned, international experience shows that the larger the universe of participants the more likely economies of scale can be developed leading to lower management fees over time. Taking this experience into account, the rolling out of NEST could be improved by lifting the limits on participants’ earnings and contributions.

Click here to respond to this post.

There is a major issue with Pension Charges and Investment performance will all UK Pension providers, in fact I have created a number of free calculators and some supporting information about this

The facts around pensions are these:-

Personal pension charges are a disgrace given the options for investment in this modern world.

Annuity returns – are a disgrace, many advisers also talk about the options of income drawdown, but these are also so highly charged it makes them not viable – with a pension of £100k you could end up paying over £15k in charges and another £4k in tax over 5 years – based on the average.

Investment returns – more than 60% of average pension fund performance from more than 1100 hundred pension funds have not returned enough to cover pension charges over the last 10 years.

The government has been lobbied hard by the industry not to bring in changes and this seems to have worked, but you really need to get a handle on this personally if you want to have a happy retirement.

Richard Smith