Conducting a systematic review of all the available empirical evidence, Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart found clear evidence that money itself does make a difference to children’s outcomes. Spending £1,000 on raising household incomes would have a similar impact on children’s schooling outcomes as spending £1,000 on schools. However, raising household income would impact many different outcomes at the same time. Income affects children’s social and behavioural development and health outcomes, as well as intermediate factors such as parenting, maternal depression and children’s home environment. Raising incomes is therefore vital in improving children’s outcomes.

Conducting a systematic review of all the available empirical evidence, Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart found clear evidence that money itself does make a difference to children’s outcomes. Spending £1,000 on raising household incomes would have a similar impact on children’s schooling outcomes as spending £1,000 on schools. However, raising household income would impact many different outcomes at the same time. Income affects children’s social and behavioural development and health outcomes, as well as intermediate factors such as parenting, maternal depression and children’s home environment. Raising incomes is therefore vital in improving children’s outcomes.

It is well-established that children from lower income households do less well than their better off peers, on a range of measures including health and education. What has not been clear is what exactly is driving these differences: does money itself matter for children’s outcomes, or is this relationship explained by other associated factors such as parental education or parenting style? Untangling this issue has important implications for policy solutions: in order to improve children’s outcomes should policymakers focus on raising household incomes or would investing in schools and parenting classes be more effective?

This has long been an important issue, but is particularly topical at present. An Independent Review on Poverty and Life Chances in 2010 called for resources to be shifted away from the tax credit system and instead directed towards parenting programmes and services for young children. The Coalition Government has consulted on redefining child poverty, with a view to giving less weight to income, whilst incorporating measures of worklessness, family breakdown and educational failure. All this at a time when the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission has found the number of children in absolute poverty has increased.

Given the importance and uncertainty regarding the relationship between money and children’s outcomes, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation commissioned us to examine the evidence on the matter. We conducted a systematic review of all the available research from EU and OECD countries that tested whether money has a causal impact on children’s outcomes. We had very strict criteria for what counted as causal evidence and only included studies that used particular methods to rule out the possibility that it was anything other than money affecting the outcomes they were measuring.

From over 46,000 search results just 34 studies passed the test. The results from these studies provide clear evidence that money itself does make a difference to children’s outcomes. In fact of the 34 studies only 5 do not find money has an impact, and in 4 of these cases there appear to be methodological reasons that may explain the results. Furthermore money has a greater impact on those with less; that is to say that an additional pound makes more difference to children in lower income households than for those from richer households.

In terms of our policy problem though it is not enough to find money has an impact; what policy-makers want to know is how much money matters. Would we still do better to invest in schools or other interventions? Whilst it is difficult to standardise results across the 34 studies, our calculations based on the more conservative estimates suggest that increasing income by around £6,000 in households where children are eligible for free school meals would halve the gap in attainment at age 11 between children on free school meals and those not on free school meals. This is roughly the amount of money it would take to bring household income for children with free school meals in line with the average income for other children.

These results demonstrate that the effect of income is sizeable, but leave the question of preferred policy solutions still open. If we compare the effects of income to effects of spending on other interventions the implications of the results become clearer. Studies of school education expenditure in England have found the effect on children’s cognitive development to be similar in size to our lower-end estimates. So it seems spending £1,000 on raising household incomes would have a similar impact on children’s schooling outcomes as spending £1,000 on schools. However it is important to note that the evidence shows money has an impact on a range of children’s outcomes at the same time. Income affects children’s social and behavioural development and health outcomes, as well as intermediate factors such as parenting, maternal depression and children’s home environment. Few other policy interventions are likely to impact as many different outcomes at the same time.

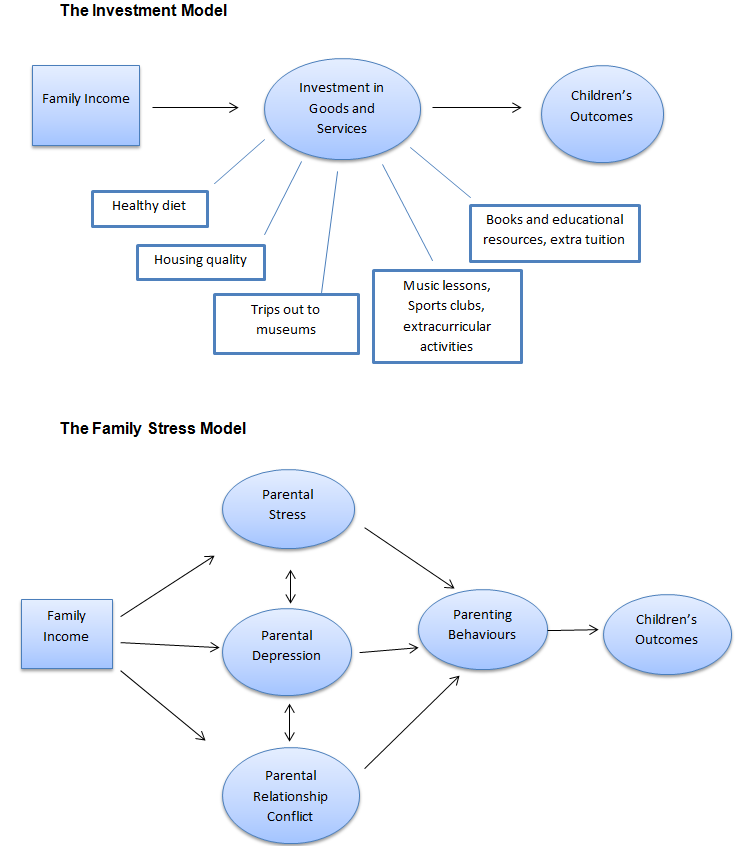

Whilst two-thirds of our 34 studies come from the US, the mechanisms through which income appears to affect children’s outcomes are likely to be equally relevant to the UK. In terms of explaining how income affects children’s outcomes we found evidence for two central theories. One relates to the direct impact of income on children’s physical environment, through parents’ abilities to afford goods and services that are beneficial for children (the investment model). The other outlines the indirect effect through the stress and anxiety caused by having a low income, which undermines parents’ capacities for nurturing and positive parenting behaviours (the family stress model). As well as reinforcing the relevance of the evidence from US and other countries to the UK context, evidence of these mechanisms further highlights the limited effectiveness of improving children’s outcomes by solely investing in services, particularly if household incomes remain low. This is especially true in the case of the family stress mechanism, for which the evidence is strongest.

Figure 1: The Investment Model and The Family Stress Model

Overall then, there is strong evidence that income has a causal impact on children’s outcomes. Poorer children have worse cognitive, social-behavioural and health outcomes in part because they are poor and not just because poverty is associated with particular household and parental characteristics. The effect of income is comparable to those identified for spending on schools, but income influences many different outcomes at the same time and has a bigger impact on those who have less to start with.

This has worrying implications in the current economic climate, as reductions in household income and increases in income poverty are likely to have wide-ranging negative effects for children. The Coalition Government has argued that reducing welfare budgets is necessary in order to limit cuts to essential public services, with the aim of protecting children’s life chances. This strategy is likely to be self-defeating: rising income poverty will damage the home environment in ways that will make it hard for public services to deliver for children. The evidence suggests that investing in services is not enough; raising incomes is vital in improving children’s outcomes.

This article is based on a report by Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Does Money Affect Children’s Outcomes: A Systematic Review

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Kerris Cooper is a researcher at the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) and a PhD student in the Department of Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She has previously conducted independent research into people’s experiences of the Job Centre and was a researcher for Reading the Riots, a research project with the LSE and the Guardian newspaper into the causes of the UK riots in 2011.

Kerris Cooper is a researcher at the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (CASE) and a PhD student in the Department of Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She has previously conducted independent research into people’s experiences of the Job Centre and was a researcher for Reading the Riots, a research project with the LSE and the Guardian newspaper into the causes of the UK riots in 2011.

Dr Kitty Stewart is Associate Professor of Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Research Associate at CASE. She is interested in the impact of income poverty and inequality on individuals and on society at large, and in the effectiveness of different policy solutions. Recent work has focused on policy for children under five, including an assessment of the record of the last Labour Government.

Dr Kitty Stewart is Associate Professor of Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Research Associate at CASE. She is interested in the impact of income poverty and inequality on individuals and on society at large, and in the effectiveness of different policy solutions. Recent work has focused on policy for children under five, including an assessment of the record of the last Labour Government.

1 Comments