Charlie Cadywould writes about the long-term demographic issues that divide Britain and explains how they may impact on the Labour vote as we head into the middle decades of the twenty-first century.

Charlie Cadywould writes about the long-term demographic issues that divide Britain and explains how they may impact on the Labour vote as we head into the middle decades of the twenty-first century.

Just a few weeks ago, British progressives were still in a sombre mood about their future. With a landslide for Theresa May an apparent certainty, Labour looking divided and set to lose seats for the fifth election in a row, many were wondering whether the left could ever hope to govern again.

The context has shifted dramatically in a very short space of time, and Labour now is in a position to win the next election. It appears to have succeeded in uniting progressives around a single banner, in contrast to mainstream social democratic parties across Europe, which have slumped to historic lows, losing voters to the centre right, populist right, populist left, and regional separatists.

The British left should be optimistic, but there are also a number of reasons – short- and long-term – why it still faces significant challenges. The short-term challenges won’t come as a huge surprise: there is still an electoral mountain to climb to win the kind of working majority required for a transformative government; Labour still struggles with the voters it needs to win, particularly lower-middle class ‘C2’ voters; and the public is still wary of trusting Labour to run the economy.

The long-term challenges are structural, and are impossible, or at least much more difficult, to fully overcome. Instead, progressives will just have to work around them, bridge tricky divides, and find new routes to electoral success. In our new paper The Broad Church, we identify three key challenges: the changing role of class in politics, new emerging demographic divisions, and broader shifts in public attitudes.

Challenge one: class politics

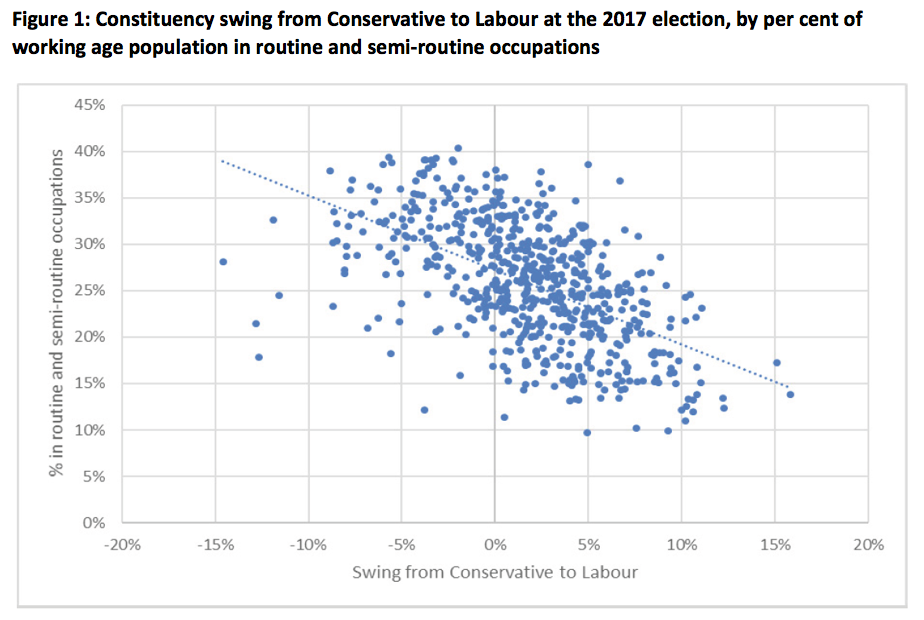

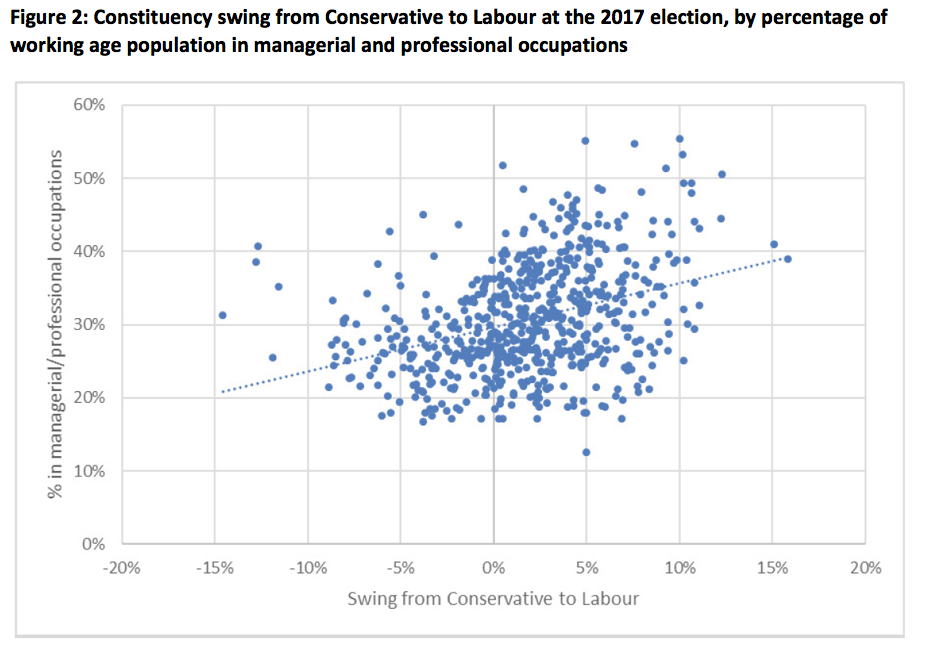

Voting in Britain has become steadily less divided along class lines in recent decades. In the 1964 election, the Tories won the middle class vote by 40 points, while Labour had a 36-point advantage among working class voters. By 2015, the leads were 12 and 0 points. However, the decline in class voting along traditional lines has occurred precisely because of class-based swings: working class voters have gradually left Labour, while it has made progress among the middle class. Early evidence suggests this continued in the 2017 election: areas with more people in lower end ‘routine’ and ‘semi-routine’ occupations swung towards the Conservatives, while areas with more professionals swung towards Labour.

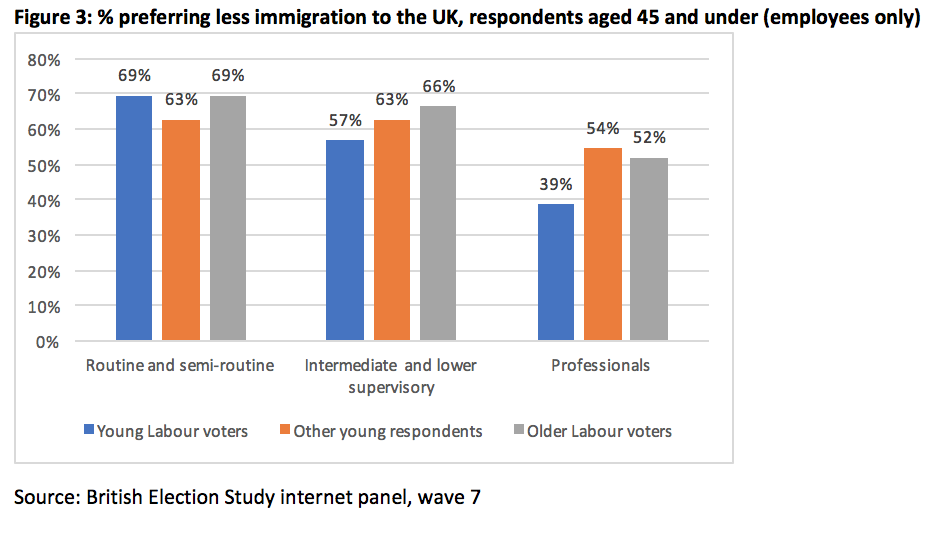

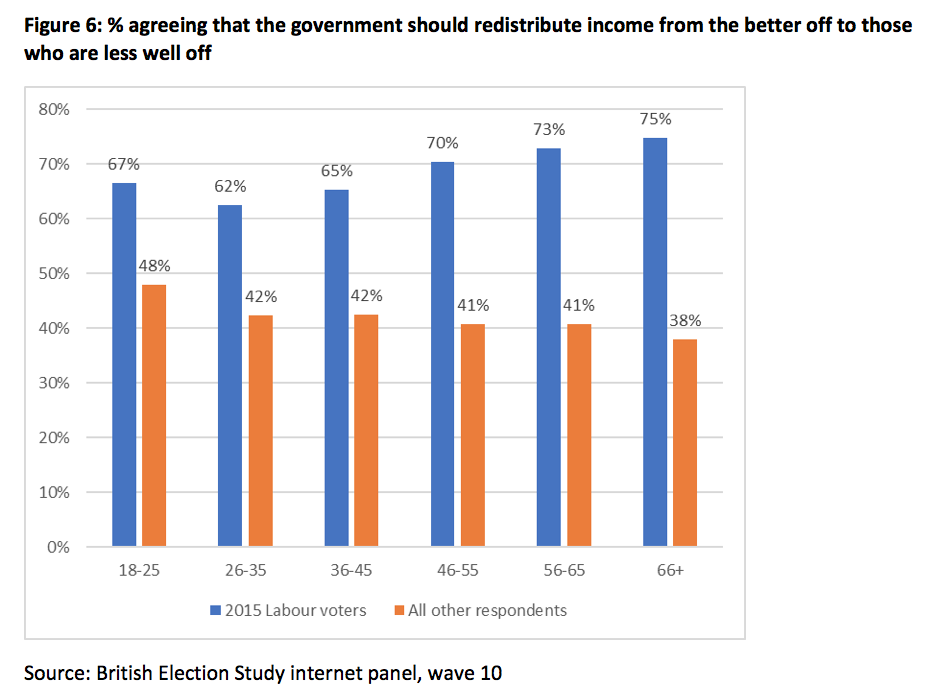

This is accompanied by some pretty strong class-based attitudinal divides. Most troubling for Labour, though is that these class divides are most visible in one section of the population: younger Labour voters. Evidence from British Election study data (using 2015 voting patterns – data is not yet available for 2017) shows that Labour voters aged 45 and under were more divided along class lines, both when compared to others of the same age, and to older Labour voters. Here are just two examples: attitudes to immigration and to redistribution. There is a class divide among all three groups, but the biggest gap in both cases is younger Labour voters.

In some ways, of course, the decline in class voting has been a lifeline for Labour: the traditional working class is in decline, and fewer people now strongly identify as working class than in the 1980s. It could not have survived without picking up more middle class votes.

Moreover, parties necessarily represent a diversity of opinions, and the Conservatives do not have a unified electoral coalition either. But it is notable that the younger portion of Labour’s base – the group that it needs to hold on to if it is to consistently win elections in the 2020s and 2030s – appears to be particularly divided along class lines, on key issues. Bridging these divides will likely be a consistent challenge for Labour.

Challenge two: the new divides

As voting along traditional class lines has eroded, new demographic divides have emerged, and as many commentators have observed, Labour’s voter coalition looks increasingly like that of the US Democrats, which is comprised largely of young people, the university educated, ethnic minorities, women, and those on the lowest incomes.

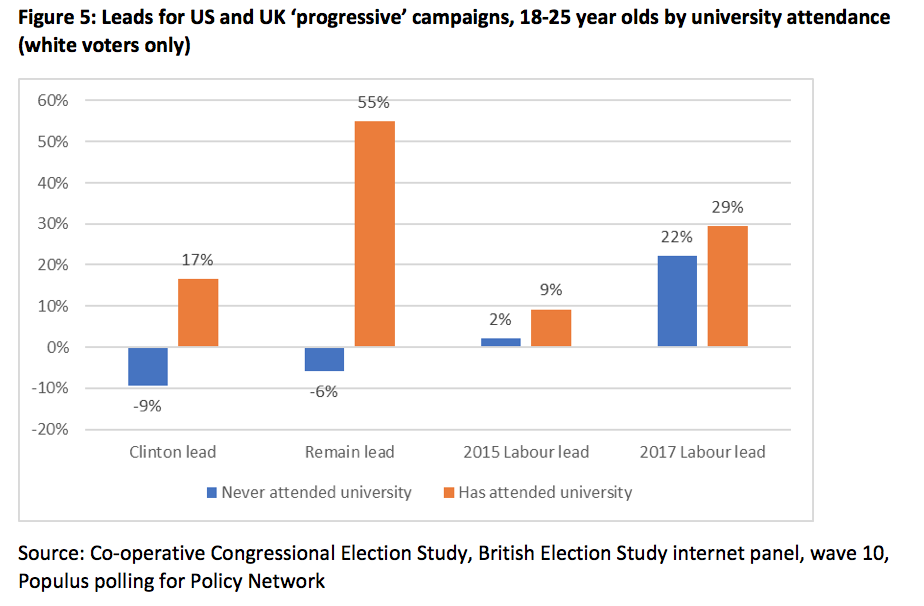

However, the UK’s demographics mean a US-style progressive coalition alone is unlikely to deliver a governing majority for Labour. Compared to the US, the UK has a relative lack of ethnic diversity. It also has an ageing population – today there are two people aged over 65 for every one aged 18-24. By 2039, the ratio will be three to one. Britain also lacks the ‘culture war’ issues that have driven a large gender divide in the US, though it’s possible some of this will surface as a result of the Conservatives’ deal with the DUP. Further, while education levels were an important predictor of voting behaviour in the 2016 US election, in the UK, education has been partially a proxy for age – the fact that a higher proportion of young people have attended university than older people significantly exaggerates the importance of education in predicting voting behaviour. This was the case both in 2015 and 2017, but not in the 2016 referendum.

In combination with the fact that Britain is rapidly getting older, what this means is that Labour’s likely future strength depends heavily on one question: will today’s young Labour voters continue to vote Labour, or will they abandon progressive politics as they get older? Is Labour’s youth surge an ‘age effect’, or a ‘generational effect’? The evidence from previous generations suggests that both play a role to varying degrees, but only time will tell if the same patterns are to emerge for millennial voters.

Challenge three: shifting public attitudes

While today’s young people are more socially liberal and more likely to vote for left-of-centre parties, they are less left-wing, for example on attitudes to redistribution, than previous generations were at the same age. On some measures, such as in Ipsos MORI’s Millennial Myths and Reality study, millennials are even less left-wing than older voters today. As with class, the generational divide is particularly strong among Labour voters.

On some measures, there also appears to have been a steady slide towards social liberalism within each generation, but away from traditional left-wing values. The Ipsos MORI study, for example, shows a decline from the late 1980s to 2014 across all generations in the proportion supporting higher welfare spending on the poor. However, NatCen’s British Social Attitudes survey finds rising support since 2010 for increased taxation and spending, and in favour of redistribution from the rich to the poor. Either way, Labour faces a challenge keeping hold of millennials who, despite overwhelmingly backing the party in June, might be less inclined to support the traditional policy levers of the left’s efforts to reduce inequality.

There are reasons to be optimistic, but there are strong, long-term reasons for progressives to be cautious as we head into the middle decades of the twenty-first century. The June election revealed yet again just how divided the public is on key policy matters. Labour, if it is to dominate the next political era, as the Conservatives dominated much of the twentieth century, it must find a way to straddle these divides.

_______

Note: the above draws on the Policy Network paper ‘The Broad Church‘.

Charlie Cadywould is a researcher at Policy Network, leading its work on the future of the left. Prior to joining, he was a researcher at Demos, authoring numerous reports on social and economic policy, as well as various analyses of public opinion and voting behaviour. He holds a BA in social and political sciences from the University of Cambridge and an MSc in public policy from University College London.

Charlie Cadywould is a researcher at Policy Network, leading its work on the future of the left. Prior to joining, he was a researcher at Demos, authoring numerous reports on social and economic policy, as well as various analyses of public opinion and voting behaviour. He holds a BA in social and political sciences from the University of Cambridge and an MSc in public policy from University College London.

My view is that we got buy before the 1980’s when we joined the EU, so am sure they will get a good deal and we will adapt.

Brexit is the top existential dilemma for Labour. Can the leadership agree that ‘No Brexit is better than a bad Brexit’?

So how many respondents were there and where were the polls conducted?