New research by Anna Bindler and colleagues finds that young people who leave school during recessions are significantly more likely to get involved in crime than those who leave school while markets are more buoyant. The research demonstrates a disconcerting and long-run effect of economic downturns.

New research by Anna Bindler and colleagues finds that young people who leave school during recessions are significantly more likely to get involved in crime than those who leave school while markets are more buoyant. The research demonstrates a disconcerting and long-run effect of economic downturns.

Recessions typically lead to an increase in youth unemployment rates, leaving young people to face more difficulties in finding jobs. Furthermore, it has been shown that starting a career during a recession has a persistent negative effect on wages and career progression. In recent research we show that recessions have a more disturbing, substantial impact on initiating and forming criminal careers: young people who leave school during recessions are significantly more likely to get involved in crime than those who leave school while markets are more buoyant.

Youth who leave school face the choice between legal and illegal activities. Those who leave school during a recession, when youth unemployment rates are particularly high, struggle to find a job, however do not yet have financial insurance. Hence, low expectations on returns to legal activity and peer effects may lead to initial involvement in (petty) crime as well as to a first encounter with the criminal justice system.

Knock-on effects can then lead to criminal careers for the young: On the one hand, those who initially get involved in criminal activity learn the “criminal know-how”, reducing the risk of being caught for subsequent crimes. On the other hand, those who have criminal records early on in their career may reduce their job opportunities and expected returns in the legal labour market.

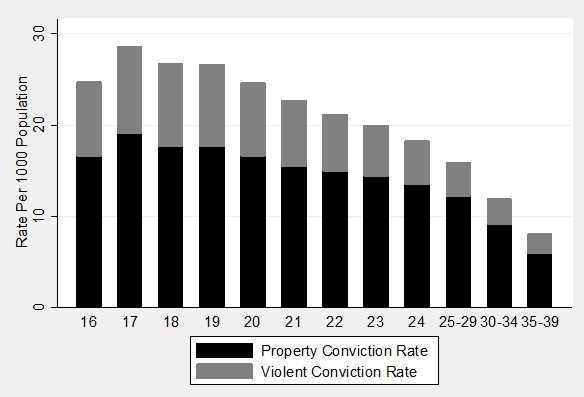

Figure 1 shows the average conviction rates by age group for male offenders in the UK between 2000 and 2010. Conviction rates peak at age groups 16 to 18 – when youth enter the labour market – and decrease but do not disappear subsequently. That suggests that there is an initial effect but criminal activity is somewhat persistent over the life cycle.

Figure 1: Male Offender Rates by Age, UK

Note: The chart shows the average conviction rate defined as the number of convictions in each age group divided by the population in each age group. The data s averaged over the period 2000-2010. Data source: Offenders Index Database (OID) and Police National Computer (PNC).

A typical recession leads to a 5 percentage points higher than normal unemployment rate. Using data on self-reported arrests from the British Crime Survey and taking into account an extensive set of individual characteristics, we find that entering the labour market during a recession is associated with a 5.7 per cent increase in the probability of ever being arrested in life. That effect is statistically significant. For individuals who leave education at age 16 and are less qualified for the labour market, the effect is even stronger.

Further, we use data on conviction rates from the Offenders Index Database and the Police National Computer to estimate the average effect of initial labour market conditions on criminal activity of cohorts entering the labour market at different times. Taking into account differences in cohort composition, we find that the average conviction rate for a cohort entering the labour market during a recession is 4 per cent higher than for an otherwise similar cohort entering a more buoyant labour market. Again, we find that the effect is statistically significant.

Strikingly, we find very similar results when we conduct the same analysis for the US. First, using individual level data from the US decennial Census and the American Community Survey (ACS) we find that entering the labour market during a recession increases the probability of being incarcerated at some point over the next two decades by 5.5 per cent. Second, using data on arrest rates from the FBI Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) and from the Current Population Survey (CPS) we find that the average arrest rate for a cohort entering the labour market during a recession is 7.5 per cent higher than for an otherwise similar cohort entering a more buoyant labour market.

How should we understand these results? The above interpretations refer to the effect on the average cohort conviction rate. Presumably, a large share of individuals in a cohort never gets involved in crime – independent of initial labour market conditions. A much smaller share is actually at the margin of becoming criminal, and in that respect affected by economic conditions when first entering the labour market. The average effect outlined above is a combination of the effects for both groups, meaning that the effect on individuals at the threshold to criminal activity is even more substantial than the average effect suggests.

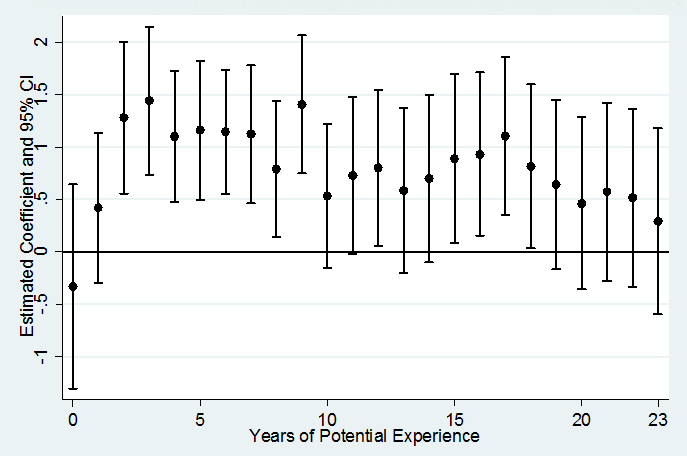

What about the persistence of the effect of recessions and the forming of “criminal careers”? Figure 2 shows the estimated effects by year since labour market entry. Albeit slightly decreasing, the effect of entering the labour market during a recession is indeed persistent: The initial unemployment effect pushes some individuals towards a criminal career, implying long-lasting sizeable effects.

Figure 2: Entry Unemployment Effects By Experience, UK

Note: The chart shows the estimated coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals when we allow the coefficient on initial unemployment to vary by years of potential experience. Years of potential experience are years since labour market entry. Data source: Own calculations.

We demonstrate a disconcerting and long-run effect of economic downturns. Recessions not only lead to short-term negative outcomes in the labour market but can indeed produce career criminals. We find robust evidence of an initially strong and eventually long-lasting detrimental effect of entering the labour market during a recession for individuals at the threshold of criminal activity. These effects are economically substantial and potentially more disturbing than short-run effects.

This article summarises ‘Crime Scars: Recessions and the Making of Career Criminals’ by Brian Bell, Anna Bindler and Stephen Machin, CEP Discussion Paper No.1284.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit: Surian Soosay CC BY 2.0

Anna Bindler is a PhD student in Economics at University College London. She has been working as Occasional Research Assistant at CEP since April 2011. Her research interests include labour economics and the economics of crime.

Anna Bindler is a PhD student in Economics at University College London. She has been working as Occasional Research Assistant at CEP since April 2011. Her research interests include labour economics and the economics of crime.