The Centre for Public Policy for Regions recently published a Briefing Note which came to the conclusion that, based on latest Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts, Scotland’s public finances would be significantly worse off than the UK over the period up to 2018-19. Here John McLaren and Jo Armstrong summarise their research and call on the Scottish Government to revise its projections of North Sea tax revenues.

One of the key issues under debate leading up to the 18th September Scottish referendum is whether Scotland would be in a stronger or weaker fiscal position compared to the UK. As part of its our ongoing research programme at CPPR, we conclude that Scotland would be significantly worse off relative to the UK over the period 2013-14 to 2018-19. In 2015-16, for example, Scotland’s relatively higher deficit would amount to almost £1,000 per head.

Our recent report considered the fiscal position of an independent Scotland relative to that of the UK based on data from key UK and Scottish Government publications on Scotland’s future fiscal balance, in particular, latest (2014) edition of the ‘Government Expenditure and Revenues for Scotland’ (GERS), which looks at Scotland’s historical fiscal balance; the latest Economic and Fiscal Outlook (EFO) by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) that supports the UK Government’s 2014 Budget Report; and the Scottish Government’s ‘Oil and Gas Analytical Bulletin’ (OGAB) from 2013.

The fiscal balance is the net financial position of the government after gross expenditure is taken away from gross revenues, so if gross revenues are greater than gross expenditure then there is a fiscal surplus, while if expenditure is greater than revenues then there is a net deficit. Our Note considers:

· Scotland’s fiscal balance excluding oil and gas revenues, that is, its onshore fiscal balance;

· The impact on Scotland’s fiscal balance of adding in potential North Sea related, offshore, oil and gas tax revenues;

· How these fiscal balances have changed in the years covered by the latest GERS report, from 2008-09 to 2012-13; in 2013-14 (for which much of the data is now close to out-turn); and for the projected period 2014-15 to 2018-19 based on the latest OBR forecasts.

For the period 2014-15 to 2018-19 we also considered how relevant oil and gas scenarios published by the Scottish Government’s a year ago, remain. We have concentrated on Scotland’s overall fiscal balance, which includes capital expenditure, for the UK and Scotland rather than the current balance, as the former reflects better the international measure that is typically used in this area of analysis. When looking at Scotland’s fiscal balance including North Sea tax revenues, we concentrate on using Scotland’s geographic share, as this is the share most commonly used by commentators. Finally, all our calculations assume that the Barnett formula will continue in essentially its current form, at least until 2018-19. To date, no UK political party has expressed any intention to amend it prior to that date, beyond the adjustments necessary to incorporate the Scotland Bill changes.]

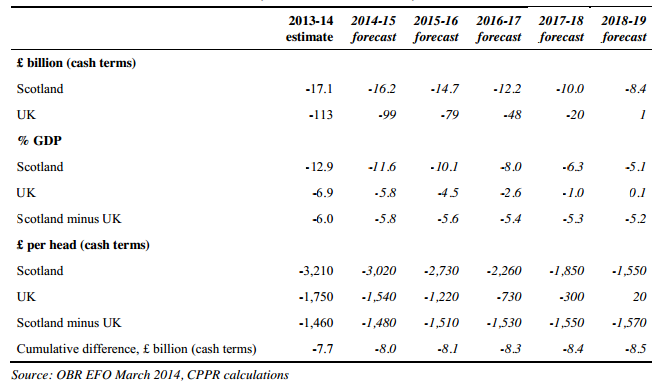

Scotland’s onshore fiscal balance has been in deficit over the period 2008-09 to 2012-13, by between 13-17 per cent of GDP, which is well above that of the UK, by around an extra 5-6 per cent of GDP (see Table 1). Due in main to the fiscal austerity measures currently being proposed by the UK coalition Government, Scotland’s future onshore deficit is projected to decline but the gap relative to the UK is not.

Table 1: Net Onshore Fiscal Balance, Scotland and the UK, 2013-14 to 2018-19

The Scottish Government’s 2014 GERS report uses an estimate for Scotland’s geographical share of North Sea revenues made by Professors Kemp & Stephens (K&S) of Aberdeen University which are at slightly higher than Her Majesty’s Revenues and Customs’ (HMRC) experimental North Sea tax data.

The latest GERS projections show that, using either a per capita measure or as a % share of GDP, Scotland’s fiscal advantage over the UK seen in 2011-12 disappears by 2012-13, as oil revenues fell by over 40%. Instead, a sizeable disadvantage emerges. Thereafter, using OBR forecasts from the UK’s 2014 Budget, we estimate that this relative UK advantage continues to grow. It is already known that total UK North Sea revenues, the main variable element in these calculations, are likely to have fallen again in 2013-14, to around £5 billion. This means that 2013-14 is more of an out-turn estimate than the sort of projection that is estimated for years beyond 2013-14.

A year ago the Scottish Government outlined four additional North Sea revenue scenarios to those made by the OBR. These were based on varying oil prices and production levels, each of which resulted in higher North Sea tax revenue projections than those of the OBR. These forecasts are now out of date and the lower than expected out-turn North Sea tax revenue data for both 2012-13 and 2013-14 have shown them to have been skewed in an optimistic manner. It would need currently unforeseen improvements in North Sea production and/or oil prices before Scotland’s fiscal balance reverted to being better than the UK’s. This is primarily due to the considerable fall in North Sea production seen over the past four years.

Based on the latest OBR forecasts, Scotland would be, in relative terms, worse off than the UK by around £1,000 per person, post-independence. This relatively poorer fiscal position, in comparison to the UK, implies either cuts to spending, or higher taxes, or more borrowing, in order for Scotland to regain the equivalent position it would be in as a part of the UK. However, OBR make no forward assumptions over what might happen to the Barnett formula or to Scottish finances if Scotland remains a part of the UK. As a result, it is not possible to be certain whether Scotland’s fiscal position under independence would be better or worse than that if Scotland stayed within the existing United Kingdom.

In assessing the future outlook, further analysis is needed on future North Sea tax revenues, with three actions recommended to help further the referendum debate:

(i) the Scottish Government should issue an updated version of its Oil and Gas revenue scenarios, given that they are now over a year out of date (something the Scottish Government’s Cabinet Secretary for Finance recently announced would now be forthcoming);

(ii) the UK Government, or the OBR, or the Scottish Government, should estimate the impact of different price and production assumptions on future North Sea revenues. This would allow for a greater understanding of the volatility surrounding North Sea tax revenues and so the extent to which the OBR’s figures are a useful guide for future planning of the Scottish Budget;

(iii) the Scottish and UK Governments should publish a reconciliation of the HMRC and the K&S differences over Scotland’s share of North Sea tax revenues.

With this additional information Scotland’s voters should have a better understanding of the range of future North Sea tax revenues for an independent Scotland so have greater clarity over its future fiscal position.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. (Credit for featured image: Berardo62)

About the Authors

John McLaren is an honorary Professor of Public Policy at the Adam Smith Business School at Glasgow University and a senior researcher at the Centre for Public Policy for Regions (CPPR). Prior to that he was an economist with H.M. Treasury and the Scottish Office and, an advisor to the inaugural First Minister (Donald Dewar) in the new Scottish Parliament.

Jo Armstrong is an honorary Professor of Public Policy at the Adam Smith Business School at Glasgow University and a senior researcher at the Centre for Public Policy for Regions (CPPR). Jo has been a micro economist in the UK’s oil and gas sector and in financial services in London and Edinburgh and was a senior civil servant in the Scottish (Executive) Government.