Research conducted by Orsolya Lelkes found that observable personal characteristics are more strongly correlated with unhappiness than with happiness. The findings suggest that unhappiness could be regarded as an undesirable personal condition as such, similar to poverty or social exclusion. Preventing avoidable unhappiness should therefore be given priority as a policy goal.

Research conducted by Orsolya Lelkes found that observable personal characteristics are more strongly correlated with unhappiness than with happiness. The findings suggest that unhappiness could be regarded as an undesirable personal condition as such, similar to poverty or social exclusion. Preventing avoidable unhappiness should therefore be given priority as a policy goal.

Should public policy focus on minimizing unhappiness rather than maximizing happiness? Subjective well-being variables, such as self-reported life satisfaction or happiness, are often treated as continuous variables or ordinal ones, assuming that there is a single latent variable behind them. I challenge this view.

My research, using a cross-sectional cross-national dataset with about 57000 individuals, shows that observable personal characteristics predict unhappiness more than happiness. It seems that the path to unhappiness is more visible to a quantitative researcher than the path to happiness. While misery appears to strongly relate to broad social issues (such as unemployment, poverty, social isolation), bliss might be more of a private matter, with individual strategies and attitudes, hidden from the eye of a policy-maker. Social policies thus may be more efficient if they target unhappiness. These efforts on a social level could be complemented with individual or community based strategies for promoting happiness.

Happiness and unhappiness: “a minority does the suffering”

Arguing for the focus on unhappiness appears to be riding against the tide. Is it not a step back, given the recent limelight of happiness as a measure of human and progress? Unhappiness and happiness constitute different qualities of experience. Neurophysiology confirms this, with evidence on cerebral asymmetry. Daniel Kahneman showed that emotional pain is concentrated among a minority of the population, who experience great emotional distress for much of the day.

The objective of policy should be to reduce human suffering. […] Dealing with depression and extreme poverty should be a priority. (p.397)

Mental health is a key determinant of (un)happiness. Based on evidence from the British Cohort Study, Richard Layard found that the most powerful explanatory variable of life satisfaction among men aged 34 is the mental malaise of the individual 8 years earlier (Layard 2012). He estimated the overall cost of mental ill-health due to non-employment, absenteeism from work and loss of productivity to be close to 7.5% of GDP in the UK. The health care costs equal an additional 2.3%. He argues that mental health needs to be the “new frontier for the welfare state”.

My analysis is based on the European Social Survey Data (ESS), including 29 countries and 57000 individuals. There are two variables measuring subjective well-being in the ESS: life satisfaction and happiness.

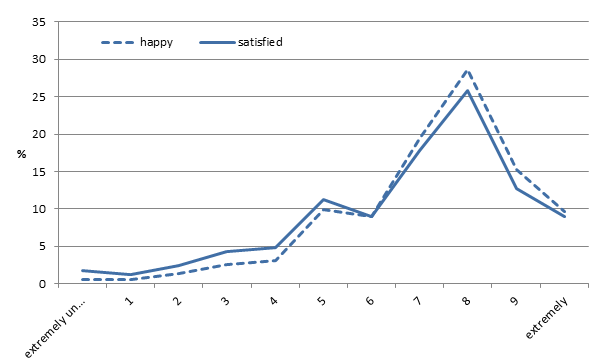

Figure 1: Distribution of self-reported happiness and life satisfaction scores, 2008.

Source: Own calculations, based on the European Social Survey, ESS4-2008 Edition 4.0

There is, as is usual, evidence of positive skew in the distribution: most people are found towards the “satisfied” end of the spectrum. I defined two groups, those with low levels of well-being and those with high levels.

Observable personal characteristics are more linked to “misery” than to “bliss”

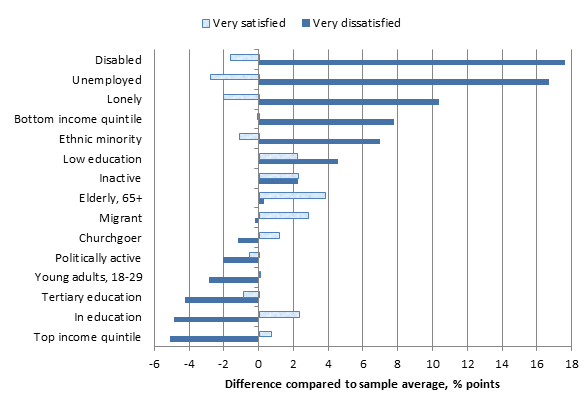

The social patterns of dissatisfaction suggest that those groups which are typically identified as socially excluded tend to suffer the most: the disabled, the unemployed, the poor, ethnic minorities and those who are socially isolated, tend to have a much greater chance to be dissatisfied (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Share of very satisfied and very dissatisfied individuals with specific characteristics: difference compared to the sample average, % points.

Source: Own calculations, based on the European Social Survey, ESS4-2008 Edition 4.0

Notes: Very dissatisfied: self-rated life satisfaction with scores 0-3. Very satisfied: score of 10.

In order to test the relationship between specific personal characteristics and well-being, I run logit models, exploring and comparing the probabilities of dissatisfaction and that of high satisfaction. I tested the results using three alternative specifications, using self-reported happiness and keeping the same cut-off point, and using a more generous cut-off point for both life satisfaction and happiness measures.

The results confirm that the dissatisfaction-satisfaction and the unhappiness-happiness scales are bipolar, linking two rather distinct qualities of personal experience. I found that observable personal characteristics are more strongly correlated with unhappiness (dissatisfaction) than with happiness (high satisfaction).

I found a non-linear relationship between income and subjective well-being. The relationship between high income and dissatisfaction (unhappiness) was stronger than between high income and high satisfaction (high levels of happiness). We could simply say that money is more powerful as a means for avoiding unhappiness than one for buying happiness.

I found a similar asymmetric relationship between health impairment and subjective well-being. Disability appears to increase the prevalence of “misery”, low well-being, but it seems to have a much weaker effect on “bliss”. This finding appears to confirm the hypothesis that some individuals may find a life with meaning despite their health impairment and may still be very happy with their lives. I also found that severe health impairment had a stronger (negative) relationship with high satisfaction than with high levels of happiness. Disability might thus affect the cognitive assessment of quality of life more than daily pleasures (experienced happiness) as such. This issue would need further, more specific exploration.

Preventing avoidable unhappiness should be given priority as a policy goal. Unhappiness could be regarded as an undesirable personal condition as such, similar to poverty or social exclusion, and the role for public policies could be identified. Note, however, that the so-called satisfaction paradox needs to be taken into account, i.e. the poor may be satisfied despite their adverse situation.

For more, see the article: Lelkes, O. (2013) “Minimising Misery: A New Strategy for Public Policies Instead of Maximising Happiness?“. Social Indicators Research. 114 (1):121-137.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr Orsolya Lelkes is Deputy Director at the European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research (Vienna). She holds a PhD in Social Policy from the LSE (supervisor: John Hills) and was a research affiliate of CASE. Her research interests include the economics of happiness and social inclusion, with recent articles published in the Fiscal Studies and Social Indicators Research, and co-edited books on Tax and Benefit Policies and European Inequalities. More: http://www.euro.centre.org/lelkes

1 Comments