In spite of evidence of long-running and large latent support, we have been in a state of denial about the far-right in Britain, which has fed into the growth of UKIP, writes Helen Margetts. Here, she outlines the state of the far-right and argues that we need to move towards acceptance, be alert to signals in long-running trends, and re-examine our political institutions.

In spite of evidence of long-running and large latent support, we have been in a state of denial about the far-right in Britain, which has fed into the growth of UKIP, writes Helen Margetts. Here, she outlines the state of the far-right and argues that we need to move towards acceptance, be alert to signals in long-running trends, and re-examine our political institutions.

In 2009 Peter John and I reported on research which showed that 18 per cent of people in England considered they ‘might’ vote for the far-right British National Party (BNP) in the future. The research was widely reported, with many articles reminiscent of commentary today post-Brexit. The Telegraph argued that it was about ‘rage rather than racism’ and that ‘the rise of the BNP should shock the mainstream parties out of their torpor’.

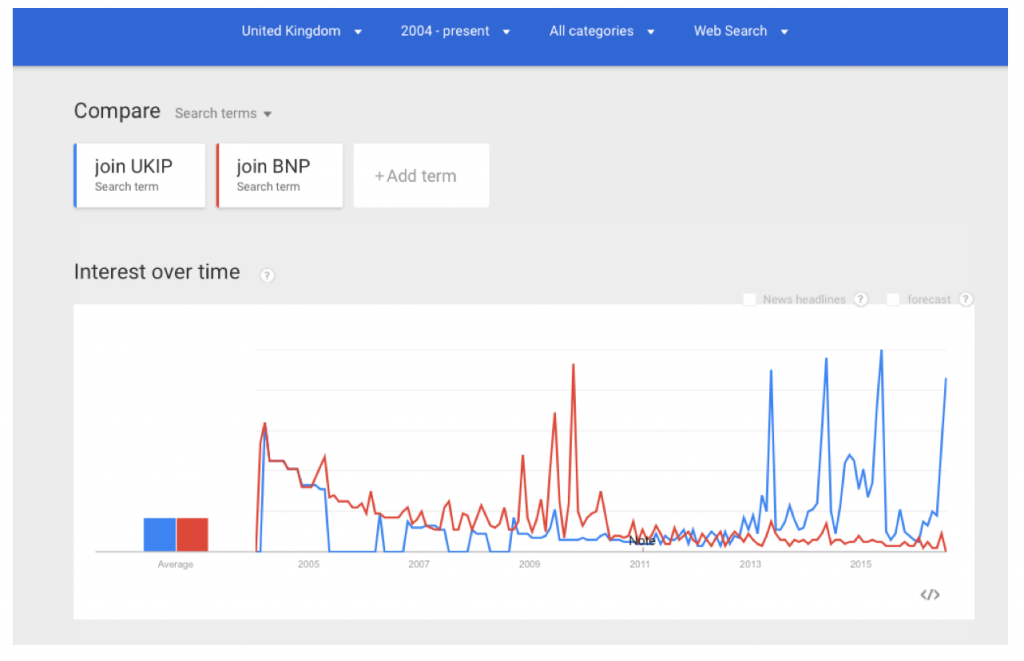

Image from Googletrends: People searching for ‘Join UKIP’ (blue) & ‘Join BNP’ (red) 20014 – 2016

Image from Googletrends: People searching for ‘Join UKIP’ (blue) & ‘Join BNP’ (red) 20014 – 2016

All this made us very unpopular with the Labour party and embroiled then employment minister Margaret Hodge in a major row for suggesting that white working class voters were turning away from Labour in response to immigration from Europe. The left – and the political establishment more generally – have always been in denial about the existence of the far-right in the UK, which is considered the exception to the rise of radical populist parties across Europe.

Since that time, the BNP collapsed financially and politically and UKIP have deepened and widened their support, culminating in the party’s key role in the EU referendum and the Leave.EU campaign. As we watch with horror complementary surges of xenophobia and fear emerging across the country and a depressing list of reports of racist attacks that grows daily, it feels like that latent support for the BNP is all around us.

British reluctance to acknowledge the existence of a home-grown far-right means that the relationship between the waxing UKIP and waning BNP has been under-explored. The exception is the admirable work of Matthew Goodwin and Rob Ford in Revolt on the Right (2014) and Goodwin’s 2012 study (with Jocelyn Evans) of far-right extremism, showing how UKIP drinks at the same well as the BNP, in that a large proportion of UKIP supporters have rather similar views to BNP supporters on issues related to race, with over half rejecting the suggestion that Britain has benefited from diversity and almost two-fifths (37 per cent) backing the idea of repatriating immigrants back to their country of origin. Such findings mirror our own earlier findings that the parties were associated with the same policies in voters’ minds; that there was a strong correlation between respondents’ attitudes to the BNP and UKIP; and that there was further correlation between micro-local support for the two parties in London elections.

But to label UKIP as the primary representative of the far-right would risk legal action as happened to one BBC presenter. Every new financial disaster (including eventual bankruptcy) for the BNP has been greeted with a collective sigh of relief, as if the support it periodically garners has evaporated with the cash. The Huffington Post did not list UKIP as one of the 9 Scariest Far-Right Parties Now In The European Parliament in 2014 and noted the demise of the BNP as ‘Good News From Britain’. And UKIP’s growing support and seeming acceptability as the face of anti-EU and anti-migration sentiment is seen as de facto evidence of the party having entered the mainstream – which means not far-right because we ‘don’t do that’ in Britain.

UKIP has presented itself as a party of patriotism and hotly denies allegations of nativism or racism, supported by Nick Griffin, ex-leader of the BNP, who claimed in 2014 that the BNP were the real “racist” party, and those who had voted for UKIP in the European elections had been mistaken. Goodwin’s 2012 study of far-right extremism was hotly contested by Farage in spite of strong evidence of policy overlaps between the BNP and UKIP, and racist and xenophobic attitudes displayed by UKIP party organisers and candidates.

Whatever UKIP claim, it seems clear that some of the latent support for the indisputably far-right BNP we observed a decade ago has transferred to UKIP. It may be ‘rage rather than racism’ that drives disaffected voters to either party, but once in the UKIP tent they are on the same side as racists and invited to identify with the same racist views and arguments in those that they seek as representatives.

UKIP was in poor shape financially and organizationally after the 2015 general election. But the referendum brought the respectable and the unrespectable onto the same side and massive funding. The campaign most associated with UKIP, Leave.EU alone spent £11 million (£10.3 million over the legal amount, currently under investigation) according to their biggest donor, Arron Banks. Just as micro-targeting and big data analytics may have won the 2010 election for the Conservatives (who spent 10 times more than Labour on personalised Facebook ads) the Leave campaigns invested heavily in targeted advertising, using the same data analytics and social media firms as some US candidates and over twice as many computational bots as the Remain campaign.

The referendum and the Leave campaigns have a lot to answer for in terms of creating a climate where nativism, xenophobia and racism, ‘spreading like arsenic in the water supply’, seems somehow legitimised. But the arsenic didn’t form spontaneously, it was there in the bedrock of UKIP support. Not all UKIP supporters are racist of course, but most racists would potentially support UKIP over other parties. Other EU leaders, more realistic and knowledgeable about the extreme right among their own populations, knew that Cameron should not have called this referendum, nor have been confident of winning it.

Growing support for UKIP has risen in the context of an increasingly fragmented and geographically heterogeneous multi-party system in Britain, fuelled by proportional systems at national and European levels. Constraining this party system through the first-past-the-post electoral system for general elections means that in 2015, UKIP received one seat for 13 per cent of the vote, rather than the 80 or so MPs that a proportional system would have delivered.

The potential mainstreaming of the extreme right has traditionally been the key argument used against the introduction of a proportional electoral system, with the strange and unsustainable assumption that if such views are excluded from electoral politics they will somehow dissipate and disappear. So UKIP’s public presence at national level takes place outside the legislature where they cannot be held to account. Farage could legitimately complain of this party’s supporters being marginalized by the establishment and the mainstream, fuelling feelings of exclusion and ‘otherness’. As an MP, he would be in parliament, representing those people that feel so excluded and dissatisfied that they wanted to vote for him and far more accountable for his claims regarding Brexit, rather than embarrassing us so shamefully in Europe, cheered on by Marie le Penn.

Now Arron Banks, funder of Leave.EU is planning to fund a new populist party based on UKIP, but more attractive to women and younger groups. The time is ripe for such a party to be successful and to make it into the Huffington Post’s top ten. UKIP’s 13 per cent support in 2015 was obviously depressed by people’s knowledge of the electoral system. But their figure for ‘might vote for this party’, our measure of latent support, was 34 per cent in the 2014 State of the Nation poll, up from 16 per cent in 2010, while for the fading BNP was still 11 per cent (as in 2010).

A new party, on the European radical right model, this time with the added weapons of big money and big data analytics, could go very far with easy access to this latent support. Trends in far-right activity are there to be observed in academic research, long-running polls and vote shares in elections at all levels, even in little snapshots of search patterns as shown above. We must read the signals.

Britain First, the successor to the BNP, got 2 per cent of the vote in the last London Assembly elections, which might be one such early-warning signal. The far-right may well go forward under the umbrella of a new populist party, buttressing supporters of UKIP and emergent small parties against the constraints of the electoral system. That should require a re-examining of every political institution, from parliament to party funding regulations to the electoral system itself. Whatever happens, just as in our neighbouring European countries from whom UKIP is so keen to escape, the far-right is firmly embedded in British politics. However long lasts the denial phase of grief over the referendum result, we have to move past denial towards acceptance regarding the far-right, in order to shape our political future.

____

Helen Margetts is the Director of the Oxford Internet Institute, and Professor of Society and the Internet at the University of Oxford.

Helen Margetts is the Director of the Oxford Internet Institute, and Professor of Society and the Internet at the University of Oxford.

I doubt that many of those who argue “against the introduction of a proportional electoral system” on the basis of how this would facilitate a political “mainstreaming of the extreme right” are assuming “that if such views are excluded from electoral politics they will somehow dissipate and disappear”. That seems like an odd straw man.

Surely most of those who argue that Britain should refrain from PR because it would empower the far right know all too well that far right sentiments are not going to dissipate. That would seem to be exactly why they are making their argument. They know the sentiments are there, they know there is little chance that those sentiments are going away anytime soon, and that’s why they argue that the current electoral system should be kept in place to at least prevent any associated party from getting hold on the levers of parliamentary power.

I don’t even agree, myself, with this cynical perspective, but little is gained by misrepresenting it.

If more parties are going to split because there can’t be any party unity on policies and campaigning, we will end up with what happens in Continental Europe. There will be more coalition governments in the future for the UK. I don’t think Cameron should be blamed for this situation which might allow Far Right parties to grow. It’s just an outcome of diversity and multiculturalism which such parties thrive on to survive but would survive regardless. They will always need what is happening in the World outside the UK to keep themselves alive in whatever form.

The only extremism in the UK is by elitist prima donnas produced at Oxford, Eton and the LSE.

To be so prejudiced against British workers struggling for decent pay and conditions is a disgrace, especially when the hypocritically illeberal do not have to suffer the consequences of mass movement in to the UK.

“Britain First, the successor to the BNP, got 2 per cent of the vote in the last London Assembly elections, which might be one such early-warning signal”

There again, it might signify that such parties are utterly marginal and stupid

Looking forward to a similar searching analysis on the Far Left, who seem to be doing a fine job taking over the Labour Party and other institutions

Surely these results represent a concern over levels of immigration. This doesn’t mean racism or even a far right perspective.