Yesterday’s report by HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) on Oakwood prison, run by G4S since April 2012, has shown how difficult it is to put the performance and culture of new prisons onto a positive footing. Simon Bastow writes about how the Oakwood case provides important lessons for government on integrating existing experience into radical reform.

Yesterday’s report by HM Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) on Oakwood prison, run by G4S since April 2012, has shown how difficult it is to put the performance and culture of new prisons onto a positive footing. Simon Bastow writes about how the Oakwood case provides important lessons for government on integrating existing experience into radical reform.

Usually when HMIP reports get picked up by the media, it is good to get some perspective by reading the short Introduction, counting the words that are positive about the prison, then counting the words that are negative, and seeing what the overall balance is. A recent report on Bronzefield prison, for example, stirred up pointed criticism by media and prison reform charities on excessive use of the segregation unit for female prisoners, but on balance the actual word count showed more positive evaluation than negative (not that this nullifies the negative of course).

In the case of Yesterday’s Oakwood prison report, there is no such net positive balance. More than four in every five words in the Introduction were plainly damning about performance of this privately managed training prison over its first 18 months.

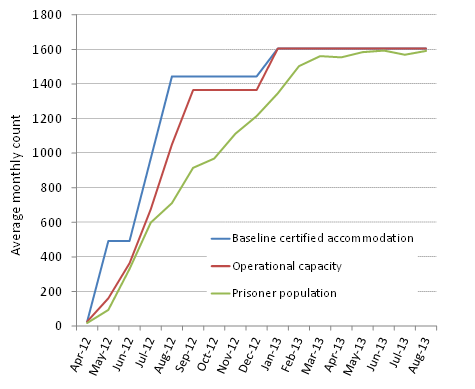

The problems at Oakwood are evident in the report. A combination of a super-charged rate of increase in the size of the prison from scratch to 1600 in less than one year (see Figure 1 below), and an inexperienced and vulnerable staff group put the prison in this precarious situation. Stress is heightened also by the fact that this is a Category C training prison, and inmates tend to get more settled for longer periods of time (compared to local prisons), and basically have more incentive to develop corrosive cultures and practices.

Figure 1: The rapid rate of increase in growth of Oakwood prison, from April 2012 to July 2013

One line of argument is that new prisons, public or private, are by their very nature difficult to open successfully. And reports from Chief Inspectors over the years have highlighted the dangers of judging new prisons too early (see p3) without giving them time to iron out problems. Most new prisons in the last few decades have been opened by private sector contractors, and so we should be cautious about how far we interpret this general problem as something particular to the private sector way of doing things.

The key difference however in the private sector is this staff experience issue. And what makes these criticisms worrying is that they echo the kinds of things that the Inspectorate was saying a decade ago about new prisons in the private sector. In 2003, for example, Ashfield and Dovegate prisons were both heavily criticized on staffing issues. The verdict on Dovegate, a Serco Cat C prison, was a ‘worrying lack of experience and confidence amongst a young, locally recruited staff, few of whom had any previous prison experience’ (p3).

As the market has matured (and it has), we would have expected that the private sector would have learnt how to open prisons from scratch, how to recruit for them from a local workforce, how to train staff on the art of prison-craft, and how to manage problems of high staff turnover.

In my own conversations with directors in recent years, signs are that the sector has learnt a great deal. G4S has run what has been widely regarded as one of the best local prisons in the estate, Altcourse, and this and other private prisons have shown the public sector how to grow experienced and well-balanced staff groups, with good gender and ethnicity mix, and run perfectly good regimes. In a previous blog, I have also shown how private sector local prisons have been consistently above-average performers on reducing reoffending since 2007.

Yet Oakwood has shown that there is a fine line between prisons that are high performing and those that fall into deteriorating patterns. We have seen this in the public sector over the years, as prisons deemed ‘failing’ are turned around in fairly short periods by ‘fixer’ governors coming in. And it is interesting that G4S responded to impending signs of difficulty earlier in 2013 by bringing in the former director responsible for Altcourse’s success, John McLaughlin, to turn around the fortunes of Oakwood. A sign of a maturing private market mirroring some well-established ‘bossist’ syndromes of the public system.

Important also is the extent to which contractors are subject to scrutiny about the experience mix of new staff groups, and how staff with proven prison experience are being integrated into new prisons to stabilize the early years. It is not always easy for contractors to get access to a ready-made workforce, and for various logistical and ideological reasons, it may be difficult to attract experienced officers from the public sector. So new private prisons must work with what they have got in that sense. But there is clearly still a major risk here. Is there a role for HMIP to report on the balance of staff experience, especially in new prisons? What percentage of staff in Oakwood, for example, had no prior experience of working with prisoners? This is important information that should be made public.

More broadly, there are important lessons for government’s radical plans to open up the provision of probation services to the private and third sector. Radical reform may be fine in and of itself, but to do so without allowing existing public sector probation trusts to submit applications to run services (either unilaterally or in collaboration with private or third sector organizations) runs the risks of exactly the same type of large-scale experience-deficit problems occurring. Government has announced funding to support mutual bids from public sector staff, but it not clear what kind of impact this will have in competition with large and well-organized private/third sector offers.

So to expect these brand new and large-scale regional probation contracts to go from scratch to high impact is naïve. But to do so while at the same time actively side-lining a vast wealth of actual existing probation experience across a whole public sector system seems to risk the same kinds of problems down the line.

This was presumably the last thing that G4S needed at the moment as they respond to claims of alleged fraudulent activity on contract payments, but reputation is too important to these large contractors, and it is likely that the next HMIP inspection at Oakwood will find marked improvements in the regime and culture. There are longer term lessons however at stake, relating to the way in which we do radical reform in our key public services. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with radical thinking, but the fact that a large contract can still go so badly wrong in what is effectively a mature market should serve as a timely reminder for government and its criminal justice reform programme.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Simon Bastow is a Senior Research Fellow at the LSE Public Policy Group. He recently published a book with Palgrave Macmillan ‘Governance, performance and capacity stress: The chronic case of prison crowding’.