John van Reenen, Nicholas Bloom, Scott Baker and Steven Davis argue that one of the factors behind the sluggish economic recovery in the US is increased policy uncertainty. In their view, the two parties and the polarisation of politics are responsible for the high uncertainty. Regardless of who wins the presidency, the two houses of Congress are likely to remain divided by party, thus increasing political polarisation. This analysis provides a clear warning for the UK regarding the negative economic effects of policy uncertainty and the dangers of political polarisation.

John van Reenen, Nicholas Bloom, Scott Baker and Steven Davis argue that one of the factors behind the sluggish economic recovery in the US is increased policy uncertainty. In their view, the two parties and the polarisation of politics are responsible for the high uncertainty. Regardless of who wins the presidency, the two houses of Congress are likely to remain divided by party, thus increasing political polarisation. This analysis provides a clear warning for the UK regarding the negative economic effects of policy uncertainty and the dangers of political polarisation.

The US has suffered a slow recovery from the biggest output drop in the post-war period. Although the recession ‘officially’ ended in June 2009, unemployment stands at 7.8%, much higher than its pre-crisis levels (4.4% in 2006).

There are many potential factors behind the slow recovery. One leading explanation (see CEP’s US Election Analysis No. 1) attributes low demand to the financial crisis and the accompanying dislocation of capital markets. Although monetary policy has been aggressive, it has reached its limits, as interest rates are close to zero and the monetary policy measures of quantitative easing have hit diminishing returns. The winding down of the stimulus spending authorised by the 2009 American Recovery and Reconstruction Act has shifted fiscal policy in a contractionary direction.

Another – or alternative – factor in a demand shock story is the increase in uncertainty. Uncertainty can retard investment and hiring as firms become reluctant to make costly decisions that may soon need to be reversed. It can lead households to adopt a more cautious stance in their spending behaviour.

Greater uncertainty increases risk premiums in financial markets, raising the cost of borrowing for firms and households. By slowing the reallocation of jobs, workers and capital, uncertainty also undercuts productivity growth and worsens medium- and long-term economic prospects. Previous research identifies additional mechanisms whereby uncertainty can undermine macroeconomic performance.[1]

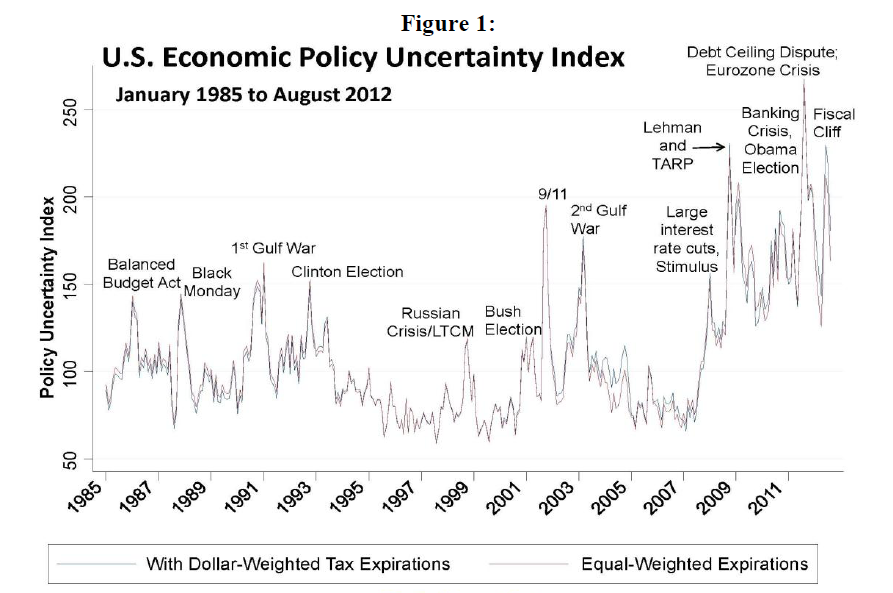

New research (Baker et al, 2012) emphasises policy uncertainty as an important factor depressing recent US output growth. This study finds that high levels of policy uncertainty foreshadow lower output, investment and employment. Figure 1 shows that an indicator of policy uncertainty spiked during the financial crisis and jumped again in recent years due to the debt ceiling crisis and stresses in the eurozone economy. In recent months, US electoral uncertainty and the so-called ‘fiscal cliff’ have contributed to high levels of policy uncertainty.

Bloom et al (2012) try to separate the effect of policy uncertainty from other factors such as low demand. This effort is challenging because demand falls in recessions tend to coincide with increases in uncertainty. Their macro-econometric model estimates that the increase in policy uncertainty after 2007 reduced employment by 2.3 million.

Qualitative evidence also suggests a role for policy uncertainty. In 2012, the National Federation of Independent Businesses undertook a small firm survey in which 35% of small firms complained about ‘uncertainty of government actions’ as a critical problem. This category was joint third alongside the ‘cost of fuel’. The top concerns, however, were the ‘cost of health insurance’ (52%) and more general ‘uncertainty over economic conditions’ (38%). Larger businesses and government agencies also cite policy uncertainty as a cause for concern.[2]

In our view, the responsibility for high policy uncertainty rests with both major political parties. But many politicians see it otherwise. Republicans blame the President and Congressional Democrats for creating regulatory uncertainty and introducing harmful regulations. They also accuse the Democrats of failing to face up to the need for reform of social security, Medicare, Medicaid and other social insurance programmes, the main long term drivers of rising debt.

Democrats, in turn, accuse Republicans of obstructionism, political brinksmanship and an obsessive focus on tax cuts and spending cuts. They fault Republicans for failing to embrace a mixture of spending cuts and tax hikes in responding to US fiscal imbalances and a lack of serious detail on healthcare reform.[3]

The roots of political polarisation

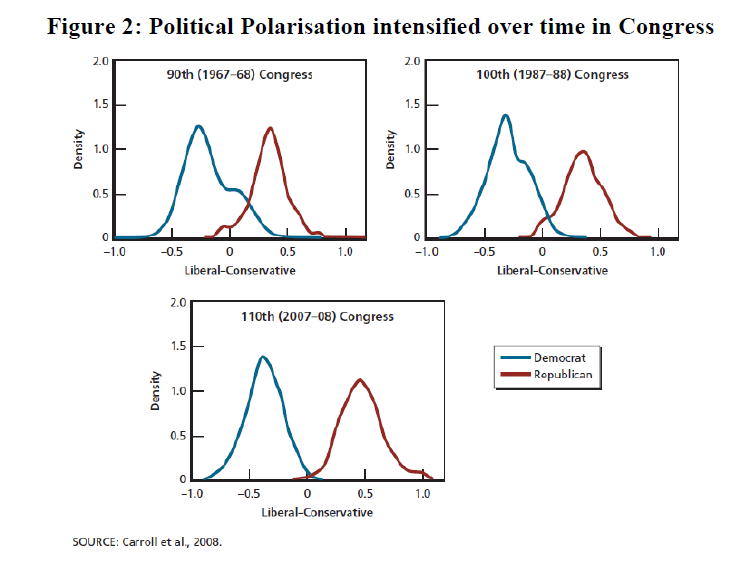

Figure 2 shows voting patterns in Congress in 1967/68, 1987/88 and 2007/08. The 90th Congress of 1967-68 showed a considerable overlap in voting patterns between Democrats and Republicans along liberal and conservative issues (see Carroll et al, 2008, for details of how this is scored), allowing the possibility of more compromise. But there was essentially no voting overlap by the 100th Congress of 2007-08.

This move to the extremes is partly due to the ability of incumbents to gerrymander political districts (that is, to change Congressional district boundaries to maximise their chances of re-election). This drives primary election campaigns to focus on appealing to their more extreme political bases rather than more moderate voters.

But the increase in partisanship goes beyond the gerrymander effect, as the Senate (where boundaries are fixed by state lines) has also become more ideologically split. The main reason appears to be that the US as a whole has become more spatially segregated along political lines. Democrats increasingly live only near other Democrats – and Republicans near Republicans (Bishop, 2008).

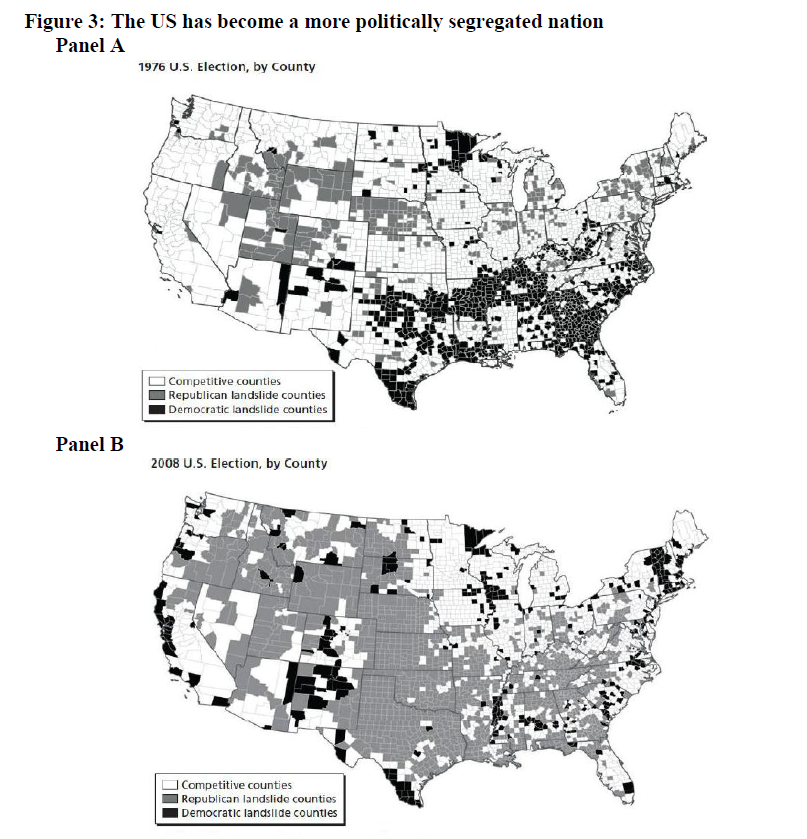

Figure 3 makes this point by showing voting patterns by county in 1967 and 2008 (county borders are not subject to political manipulation). There are far fewer competitive counties and far more landslide counties in 2008 than 40 years earlier. This development reflects the trend toward political polarisation in US society.[4]

Conclusions

It is unclear whether the November elections will significantly alleviate US policy uncertainty. A clear victory for one party could greatly clarify the policy outlook, but that outcome appears unlikely based on polling data. Regardless of who wins the presidency, the two houses of Congress are likely to remain divided by party. Thus, the increasing political polarisation of the last 30 years is likely to continue.

Until some political mechanism creates incentives to elect moderate representatives who can reach across the ideological divide, the US seems destined to heightened levels of policy uncertainty for many years to come.

This is No. 2 of the Centre for Economic Performance’s (CEP) US election analysis. All of the papers in the series can be accessed here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Scott Baker, Nicholas Bloom, Steven Davis and John Van Reenen, October 2012

For further information

Contact: Nicholas Bloom (n.bloom@Stanford.edu), John Van Reenen (j.vanreenen@lse.ac.uk) or Romesh Vaitilingam (romesh@vaitilingam.com). The Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) is a non-profit, politically independent research institution funded by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (similar to the US NSF)

[1] See Bloom et al (2007), Bloom (2009) and Bloom et al (2012).

[2] For example, see ‘Risky Business’ The Conference Board CEO Challenge 2012 and Beige Book, October 11th, 2012.

[3] See CEP’s US Election Analysis No. 3 on Healthcare for a deeper analysis.

[4] See CEP’s US Election Analysis on Inequality.

Further reading

Scott Baker, Nicholas Bloom and Steven Davis (2012) ‘Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty’, Stanford mimeo.

Bill Bishop (2008) The Big Sort, Houghton Mifflin.

Nicholas Bloom (2009) ‘The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks’, Econometrica.

Nicholas Bloom, Steven Bond and John Van Reenen (2007) ‘Uncertainty and Investment Dynamics’, Review of Economic Studies 74: 391-415.

Nicholas Bloom, Max Floetotto, Nir Jaimovich, Itay Saporta and Stephen Terry (2012) ‘Really Uncertain Business Cycles’, NBER Working Paper No. 18245.

Royce Carroll, Jeffrey Lewis, James Lo, Nolan McCarty, Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal (2008) ‘Who Is More Liberal, Senator Obama or Senator Clinton?’, Working Paper, 18 April.

Peter Orszag (2011) ‘Healthcare, Political Polarization and our Fiscal Future’, CEP 21st Birthday Lecture.

1 Comments