A key task for forecasting UK elections is to work out how best to predict party vote shares in each constituency in the UK. The primary difficulty facing forecasters is that the main source of information for making predictions – political opinion polls – are rarely available at the constituency level. However, the 2015 election has seen a greater number of these polls than in the past, offering important constituency-level information to forecasters. In this post, the team from electionforecast.co.uk compare the latest batch of these polls to their constituency “nowcasts” from the day before the release of the polls. The results are encouraging, and provide some early support for the assumptions of their model.

So far in the run up to May 2015 only 104 of 650 constituencies have been polled directly. Lord Ashcroft has run the vast majority of these polls. In our model at electionforecast.co.uk, we attempt to overcome the dearth of constituency level polls by modeling how support for each party varies across different kinds of constituencies. We use information from the constituency polls we do have, as well as some YouGov polling data disaggregated to the constituency level, and pool this information across constituencies that are similar across a wide range of characteristics. The idea is to use information from a battery of constituency-level variables to firm up our beliefs about each individual area. We can use the information from constituencies where we have more polling data to help guide us to a ‘best guess’ of the result in constituencies where we have less (or even no) polling data.

If, for example, constituency polls indicate that support for UKIP is higher in low-income and low-employment constituencies that were polled than in other constituencies, we can infer that support for UKIP may also be relatively high in other constituencies sharing similar characteristics. Applying this logic across all constituencies, using many different variables, means that we can make better predictions of the vote share for each party in those areas where polling data is thin on the ground.

The problem is that we do not yet know if this model works. While our “retrocast” of the 2010 election gives us some confidence, until the election results are announced on May 8th, we will not know whether our model is making assumptions about these patterns that do not hold up in practice. However, one way of assessing the accuracy of our approach is to compare new constituency polls as they are released to our constituency “nowcasts” from the previous day. In this way, we treat a new constituency poll as a pseudo-election result for that constituency on that day, and see if we would have been close to getting the result right had the election been real.

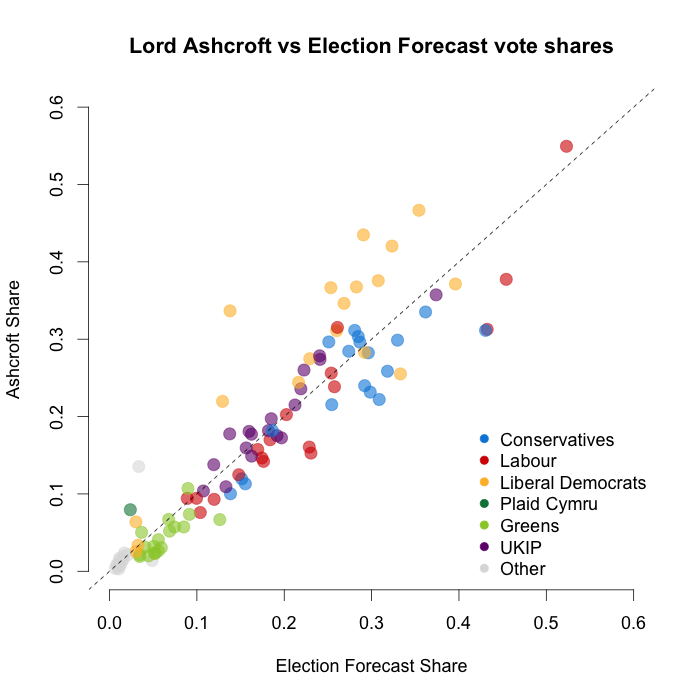

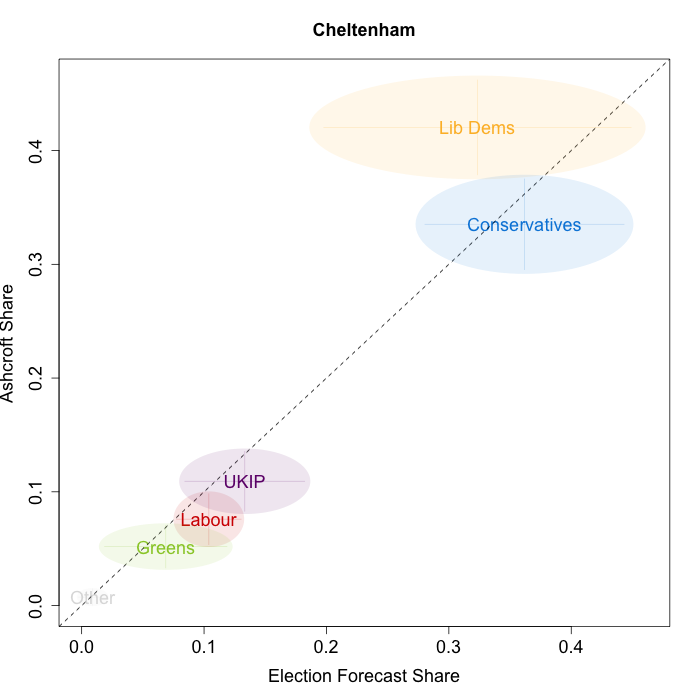

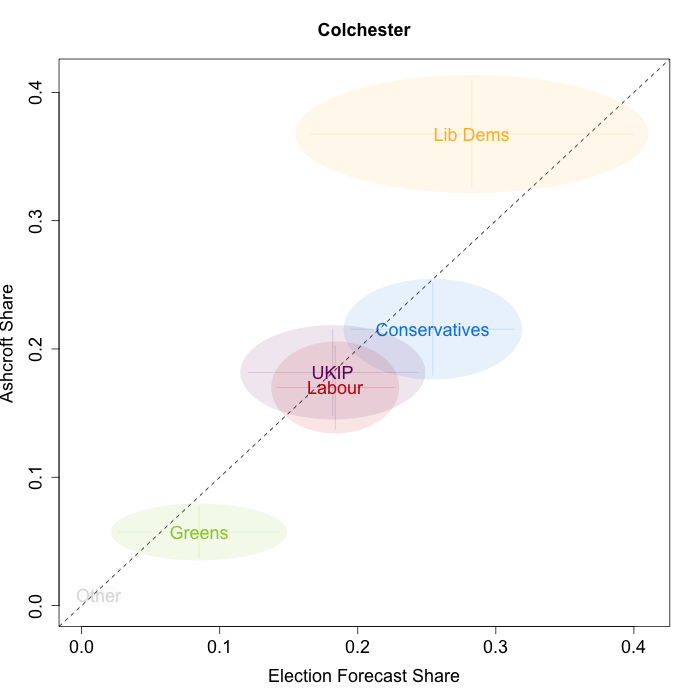

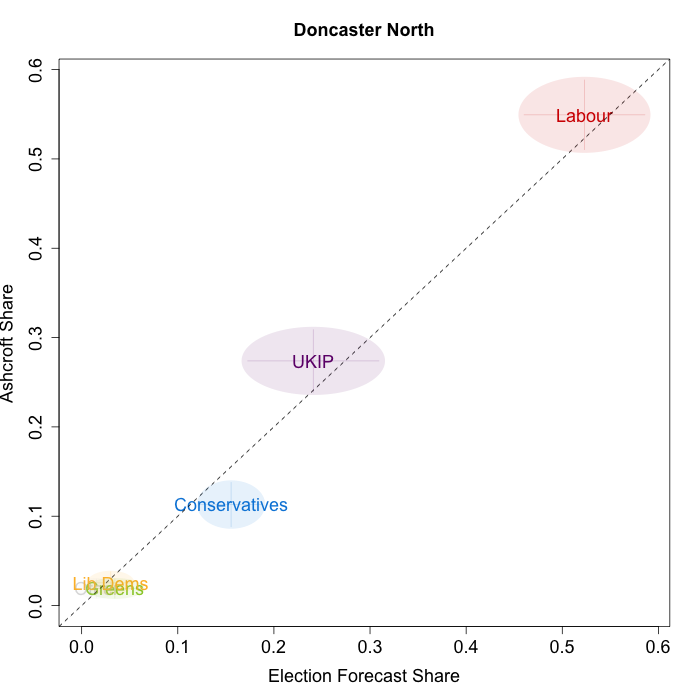

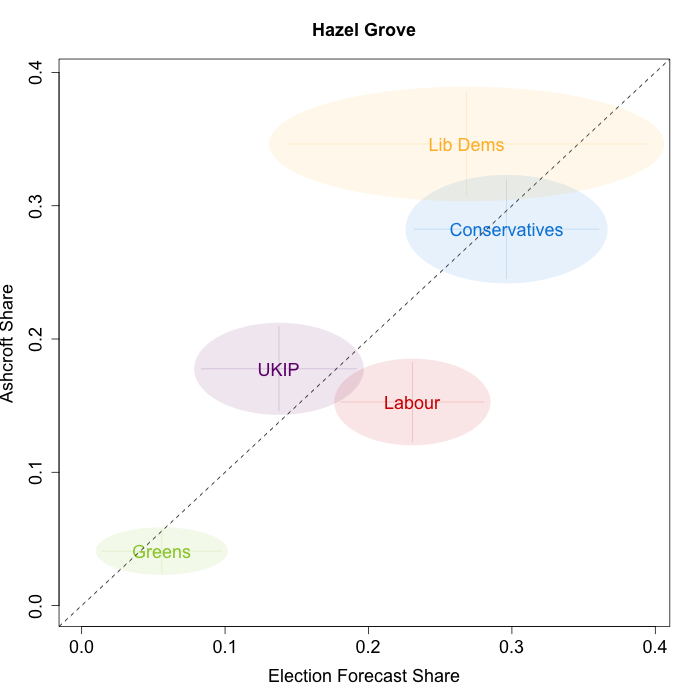

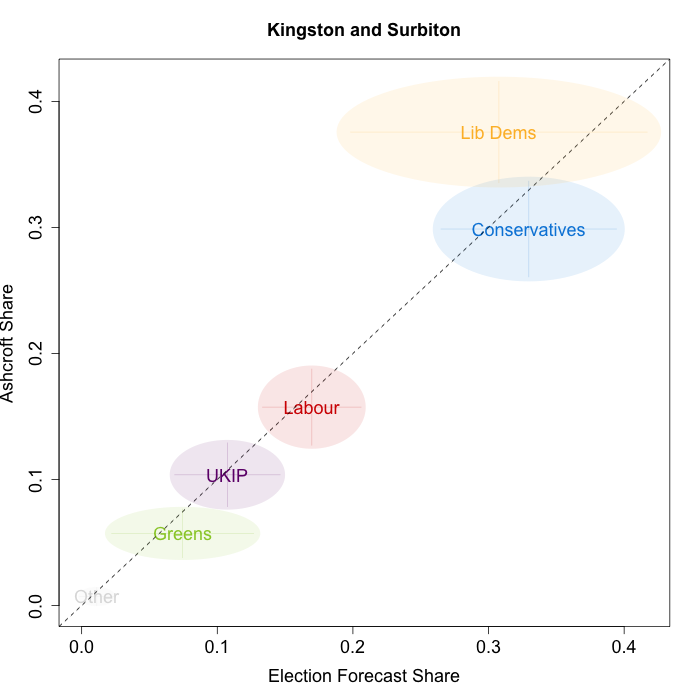

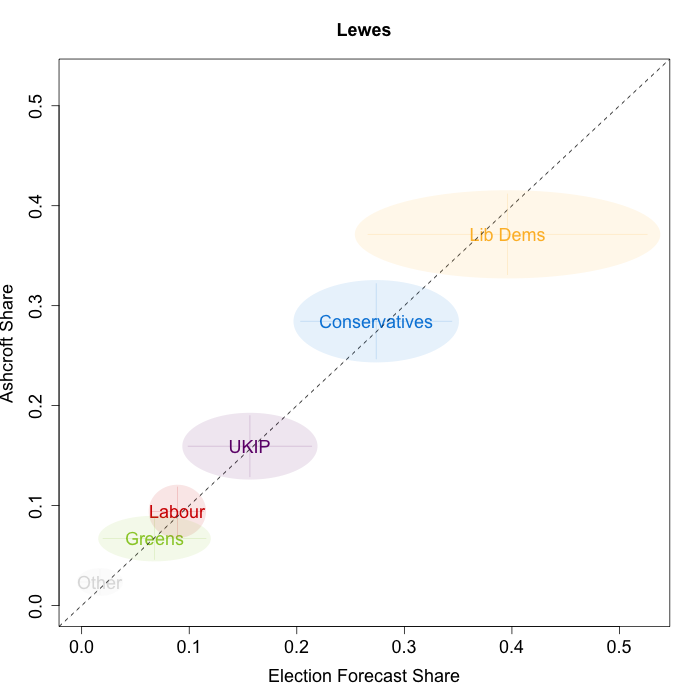

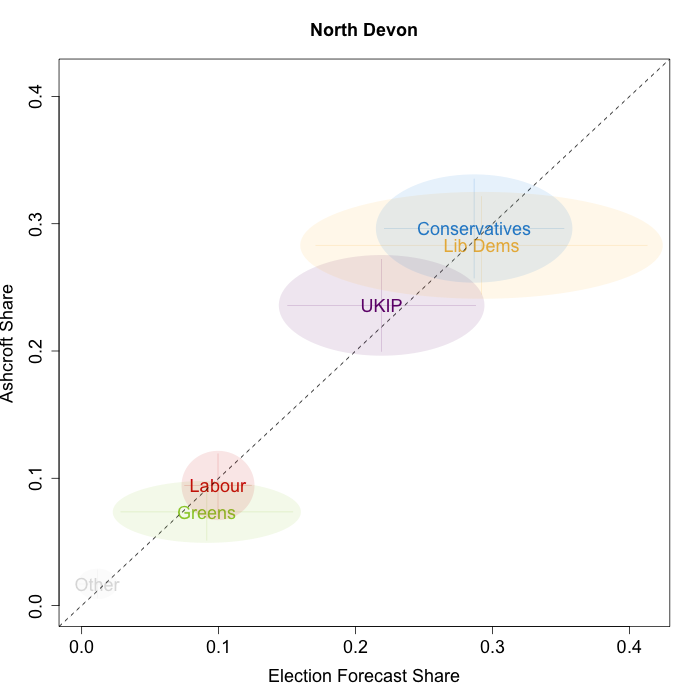

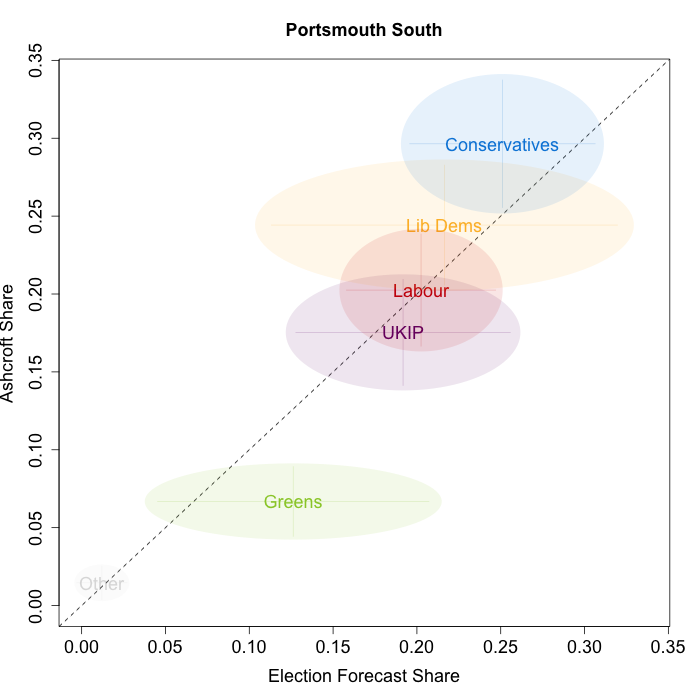

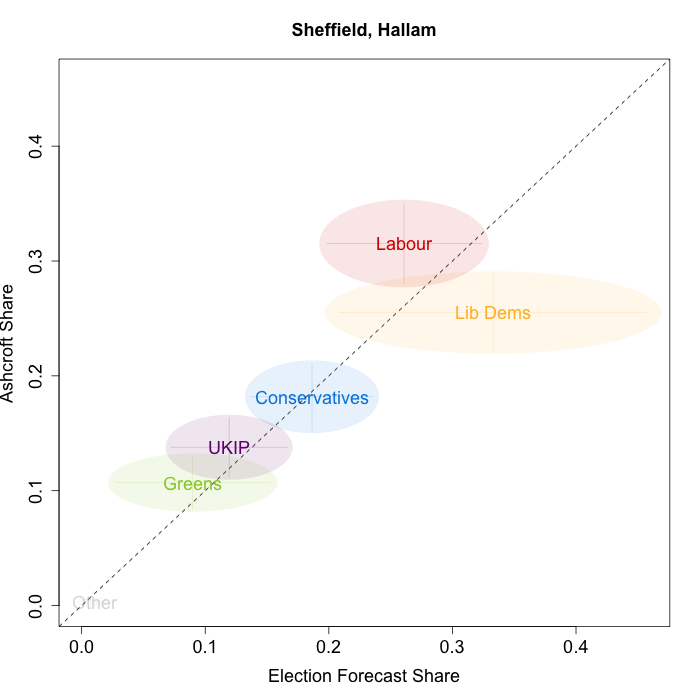

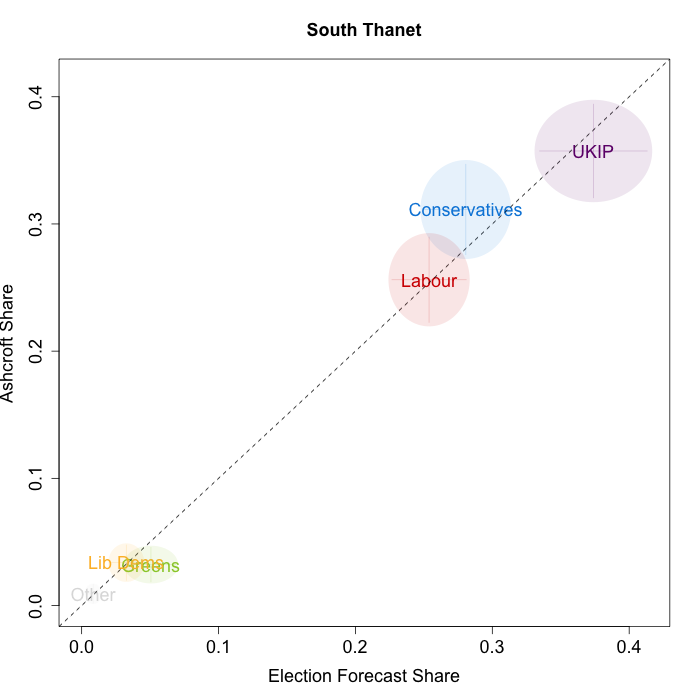

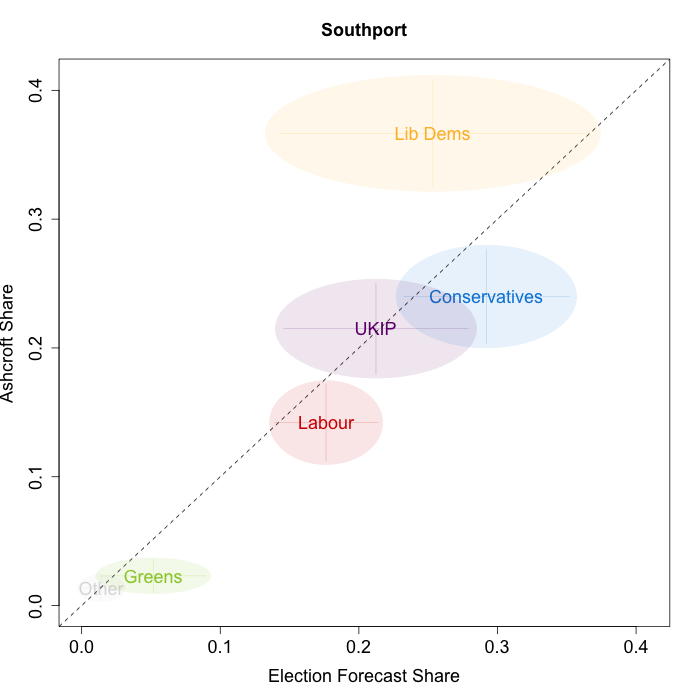

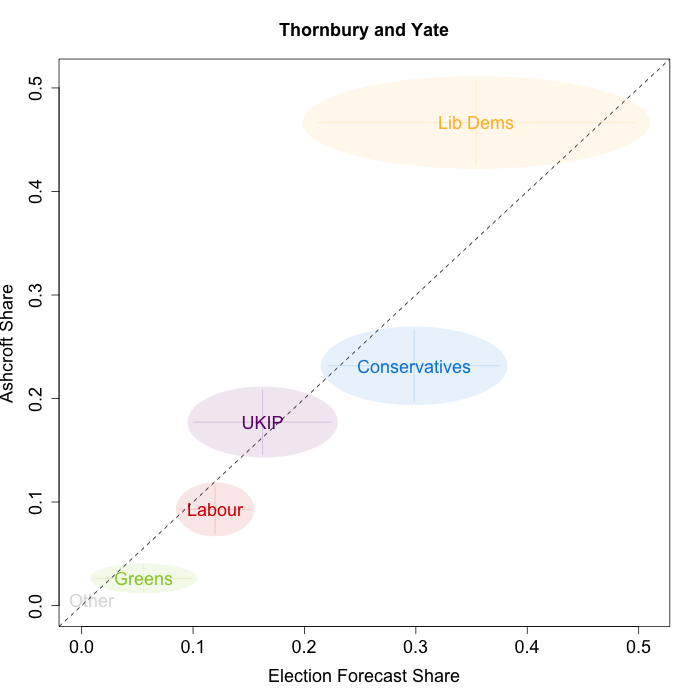

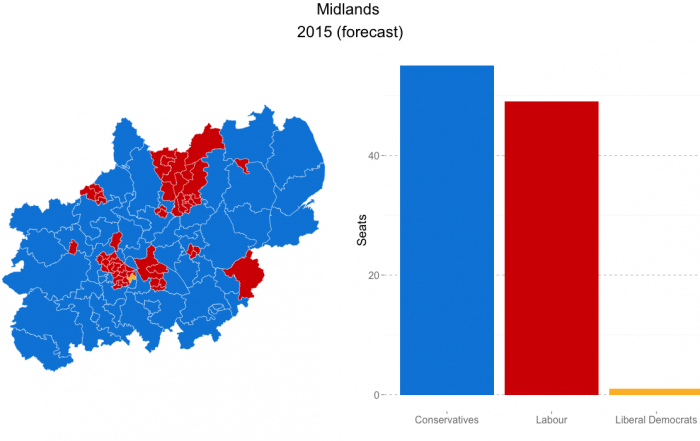

The plots below show that in general, but not in every case, we are accurately recovering the current state of play in most of the constituencies that Lord Ashcroft has recently polled. Specifically, on November 27th, Lord Ashcroft released 18 new constituency polls which provide estimates of the vote share of each party competing in each constituency. This gives a total of 107 observations of party vote shares. In the figure below, we plot our forecasts from November 26th for these constituencies on the x-axis and the Ashcroft estimates on the y-axis. As the points cluster around the dashed 45-degree line, it is clear that, in general, our forecasts correspond relatively closely to the constituency polls.

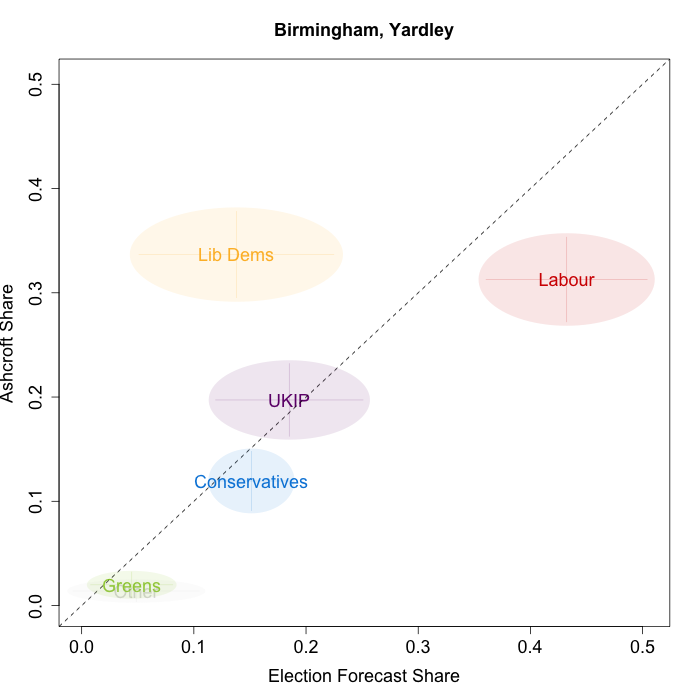

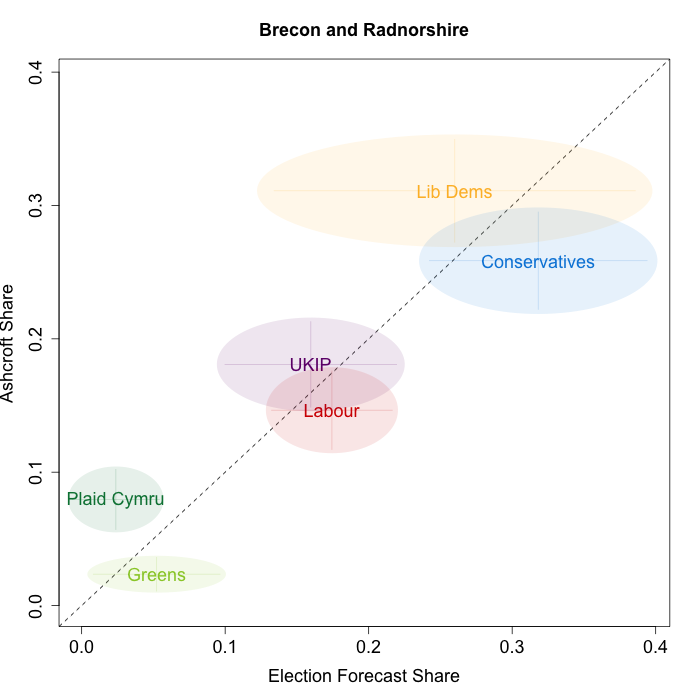

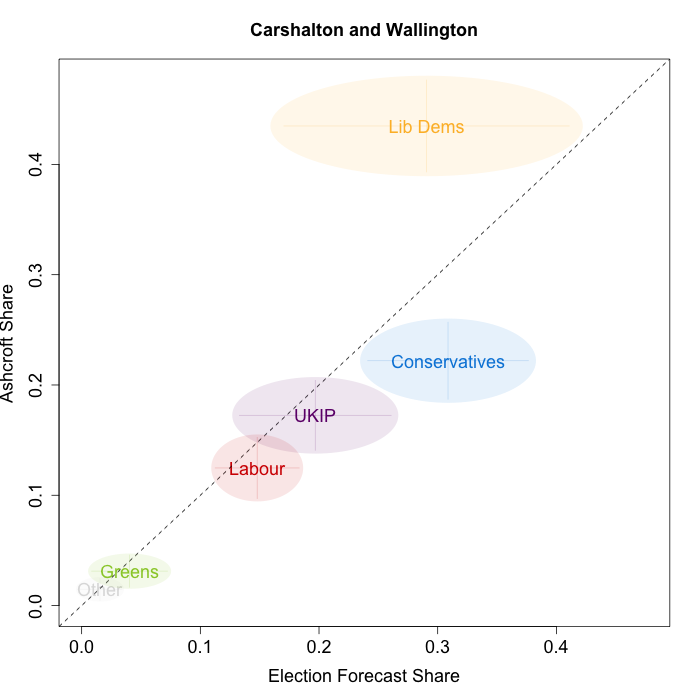

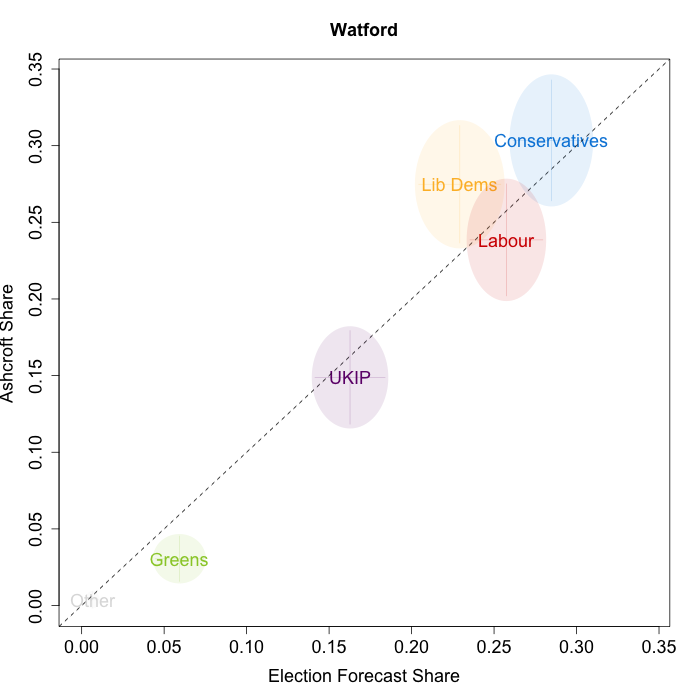

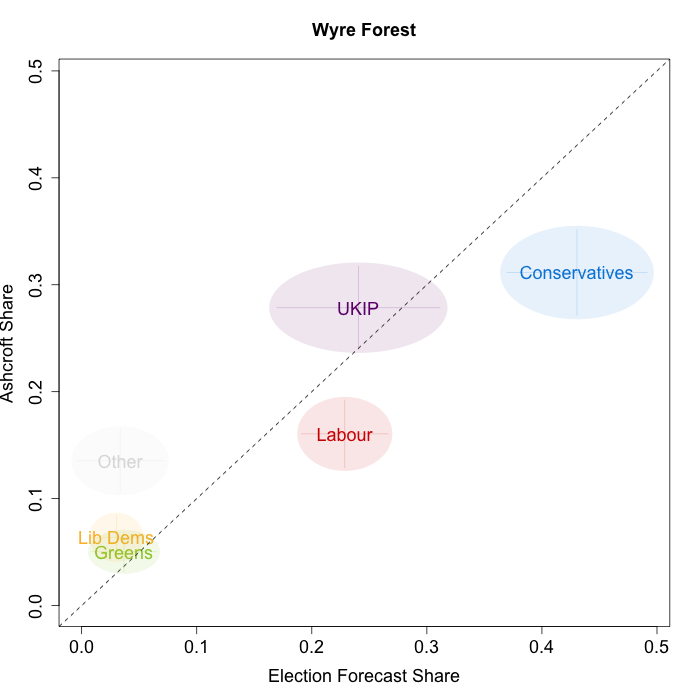

However, as both polls and forecasts include uncertainty, in the figures below we break these results out by constituency and plot ellipses capturing the joint margin of error around each point. Whenever these ellipses cross the dashed 45-degree line, we can say that our predicted vote share range for a given party, in a given constituency, coincides with the range implied by Lord Ashcroft’s polls. We find that for our forecasts from November 26th – the day before the polls were released – overlap with Lord Ashcroft’s polls in 90 per cent of cases.

Navigating through each constituency shows that we are doing better in some areas than others. For example, we are accurately estimating the current level of support in Lewes and North Devon, but are doing less well in Birmingham Yardley, where we are underestimating the Liberal Democrat vote share, and overestimating the Labour vote. Similarly, our estimates for Labour and the Conservatives are significantly larger than the Ashcroft polls imply in Wyre Forest. Additionally, we are considerably more confident in some constituencies than others. Compare, for example, the uncertainty estimates for South Thanet and Brecon and Radnorshire. South Thanet has been polled previously by Lord Ashcroft, but Brecon and Radnorshire has not. As we get more constituency polls, the precision of our estimates for previously unpolled constituencies should increase.

Overall, we are pleased at how well our model seems to be performing in these pseudo-elections, and these results give us additional confidence looking forward to the election. The largest discrepancies between our forecasts and the polls are with respect to the Liberal Democrats in the seats where they are performing strongly (according to Lord Ashcroft). This could be a sign that Liberal Democratic votes shares are more idiosyncratic, and therefore harder to model, than is the case for other parties. However, incorporating these new polls into our model should help us produce better forecasts for constituencies of this type in the future. We will continue to make these comparisons each time a new set of constituency polls are released, so stay tuned here and to electionforecast.co.uk in the coming months.

Jack Blumenau is a PhD candidate in Government at the London School of Economics.

Jack Blumenau is a PhD candidate in Government at the London School of Economics.

Chris Hanretty is a Reader in Politics at the University of East Anglia.

Chris Hanretty is a Reader in Politics at the University of East Anglia.

Benjamin Lauderdale is an Associate Professor in Methodology at the London School of Economics.

Benjamin Lauderdale is an Associate Professor in Methodology at the London School of Economics.

Nick Vivyan is a Lecturer in Quantitative Social Research at the Durham University.

Nick Vivyan is a Lecturer in Quantitative Social Research at the Durham University.

6 Comments