In his inimitable style, Ken Clarke gave indication last week of the coalition’s approach to reform of the prison system. There are reasons to be optimistic, and reasons to be sceptical. Simon Bastow discusses the reasons.

In his inimitable style, Ken Clarke gave indication last week of the coalition’s approach to reform of the prison system. There are reasons to be optimistic, and reasons to be sceptical. Simon Bastow discusses the reasons.

.

Prison reformers have got to be feeling optimistic in light of comments made last week by the new Justice Minister. Leading campaigners, such as the Prison Reform Trust, have been in communications overdrive in recent months, in the knowledge that with every new government or Minister comes a window of opportunity to get some basic messages across about the depressing economics of an ever-growing prison population.

Reformers are right to be optimistic. Conditions have somehow transpired which seem highly conducive to reform, both in the way we use prison and in the credibility of alternative non-custodial options for punishment.

For a start, the new coalition has brought the need for some kind of ‘circle-squaring’ consensus on prisons. Prior to the election both parties seemed poles apart. The Conservatives were committed to Labour plans to boost prison capacity to 96,000 by 2012. Liberal Democrats wanted a freeze on prison building and supported the radical position of abolishing prison sentences of less than six months. Any new Minister in this coalition would have sat down on the first day and thought ‘how the hell am I going to make this one work?’ The sense is however that something bold and significant has to happen for it to have any chance of working.

The second conducive condition has got to be economic situation. The financial commitment to plans for expansion to 96,000 seem relatively safe at the moment, but it is not clear how this will last. The sheer lack of money available to expand prison capacity does provide a compelling argument in favour of reducing the prison population. The logic is skewed here, of course, as we are essentially relying on a form of constructive under-supply (or de facto ‘capping’ of the prison population) to limit the extent of demand.

If we are honest, the Treasury has been taking this line for decades, as have many liberal reformers. It is interesting in fact to watch liberals reconcile themselves with the uncomfortable idea that they are on the same side as the Treasury on this point.

The problem is with limiting the supply-side is that it runs the risk of having to tolerate a return to increased overcrowding in prisons if the prison population does not start to decrease. And many officials in the prison system are currently worrying about the prospect of having to return to the ‘bad old days’ of tripling prisoners in cells designed for one.

The third reason to be hopeful is that Ken Clarke is Minister for Justice. He is a big hitter, an eminently pragmatic politician, and an insider with the judiciary. More importantly, he is at a specific point in his career where he has relatively little to lose, and can be a bold reformer without worrying too much about career implications.

As Home Secretary in the early 1990s, Clarke was on the way up in terms of his political career, and few Home Secretaries in that position have seen sense in risking this by being bold on an intractable and potentially ‘no-win’ issue such as prisons.

He came to the prison system at an absolutely critical time in the early 1990s. The 1991 Criminal Justice Act had set out broadly liberal and pragmatic agenda for change, and the report by Lord Justice Woolf and Stephen Tumin in the aftermath of the Strangeways riots had provided a compelling blueprint for change.

But pressure from the Conservative ranks to roll back more liberal reforms in the 1991 Act proved too much, and it is widely thought that Clarke reneged on the more progressive elements of the Act, by which time, he had left to become Chancellor and much of the momentum for reform from the previous five years dissipated along with him.

In these sorts of coordination problems lie the seeds for being sceptical. Looking across the last thirty years, Home Secretaries have had grand designs yet have struggled to pull all the different interests together sufficiently to bring about change. Ken Clarke is not the first Minister to make bold claims about reforming the prison system and reducing the size of the prison population. Nor will he be the last.

Labour Ministers have been criticised for presiding over the stunning increases in the prison population, but Jack Straw, David Blunkett, and Charles Clarke all came to office with a similar style of rhetoric in place for doing something about the problem, but saw their plans, by their own admission, ‘unravel’ over the course of their terms.

David Blunkett presided over major reforms to the system as a result of the first review by Lord Carter in 2003. This aimed to increase integration between prisons and probation, strengthen guidelines for sentencing, and provide credible non-custodial alteratives to prison. Senior prison officials refer to Charles Clarke’s attempts to apply his own strategic vision to the system. This came with very public declarations about the need to manage down the demand side, and the expansion of executive release schemes such as Home Detention Curfew to take pressure off the system from the back end.

Time, commitment, coordination, courage, trust, adequate resources, and a bit of luck all come into it. And for Ministers on their way up, getting alignment in all these things is rare, not to mention high risk, and requiring constant prioritization and nurturing.

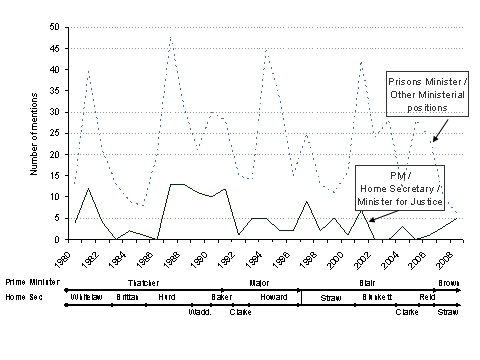

The number of mentions of the term ‘crowding’ or ‘crowded’ (or variations of) in relation to prisons by MPs and Lords in parliament

It is interesting to review of the number of times the term ‘crowding’ or ‘crowded’ (or variations of it) has been mentioned in both Houses of parliament over the last thirty years (see the Figure).

Working on the basic assumption that the more the term is mentioned by senior Ministers, the higher its priority, it is clear from this analysis that there was a sustained period throughout the late 1980s under Hurd, Waddington, and Baker, where the issue was in the minds of the most senior politicians. It is perhaps no coincidence that this period saw a reduction in the size of the prison population and levels of crowding.

Critics have documented the approach by Douglas Hurd to attempt to establish some kind of coalition on penal reform, around the objective of reducing the prison population and expanding the range of non-custodial alternatives. David Faulkner, one of the key policy architects of this period, identifies as a key part of these reforms the emphasis on sustained cooperation between policy makers, academics, prisons and probation professionals, and senior members of the judiciary.

For reforming Conservative Ministers, one of the most virulent sources of opposition comes from their own party. As one former senior Minister described it, ‘the sharpest knives come from behind’.

So, the latest version of Ken Clarke may well encounter a similar set of problems in the next year if he is serious about reforming the system. Conversative commentators have already begun to sneer in response to his comments last week.

The fact that the coalition relies on the Liberal Democrat support may well help to dilute this traditional Conservative resistance to upsetting the status quo. Of course, it remains to be seen how much of a political priority reform to the prison system will be in terms of make-or-break issues for the coalition. Liberal Democrats may be prepared to water down their commitments to prison reform once they have been in office for a few years.

The economic imperatives of cutting costs across government may well help Clarke’s case too. And the fact that he has little to lose in being bold and having a go. The prison population may have changed since he was last in a position to do anything about it, but the complexities of bringing about reform to what is essentially a long-term and chronic problem have changed little.

I totally agree i think non violent prisoners with over 4 years should be tagged freeing up space.

being allowed back into the community to find work and be able to support them selves and their families. How much of a saving would the government make.

I cant understand why HDC tagging is a no no for inmates serving 4 yrs and over? Surely after serving 18 months or more of a 4 year sentence and reaching D category status with town visits and home leave, it would be more beneficial to the government financially, to help the inmate to rebuild a strong family unit and therefore being tagged and having the supervision of probation prevent reoffending because he or she has been part of a sheltered regime and not being part of the real world [What a shock fraught with confusion].

I have been lobbying various people for a change in policy. If enough people draw this absurdity to the attention of their MPs and other influencial authorities then maybe something will change.