Research shows that in recent years university graduates have spread out across the country, with many heading north to take advantage of the greater number of public sector jobs (and many northern graduates taking advantage of the greater number of public sector jobs). Jonathan Wright of the The Work Foundation writes that the geographic effects of the coalition’s impending cuts to the public sector cannot be ignored. If the government does not act to promote more local growth, public sector cuts will hit young graduates hard, and this may lead to a talent flight from the North to the South of the UK.

Research shows that in recent years university graduates have spread out across the country, with many heading north to take advantage of the greater number of public sector jobs (and many northern graduates taking advantage of the greater number of public sector jobs). Jonathan Wright of the The Work Foundation writes that the geographic effects of the coalition’s impending cuts to the public sector cannot be ignored. If the government does not act to promote more local growth, public sector cuts will hit young graduates hard, and this may lead to a talent flight from the North to the South of the UK.

There is an emerging consensus that places outside the South East will be hardest hit by public sector cuts. The Work Foundation’s latest report Cutting the Apron Strings? The clustering of young graduates and the role of the public sector shows that young graduates – a vital group for local economic success – are disproportionately employed in the public sector in many northern cities. Public sector cuts could not only lead to an increase in youth unemployment, but to a ‘brain drain’ of talented young people from public sector dependent towns and cities predominantly in the North to the South East in search of work.

The coalition is committed to ‘rebalancing the economy’ and creating enterprise in places that have relied upon the public sector in recent years. Doing so would allow these cities to attract and retain more talented individuals. This is urgent and necessary, but the government’s choice of policy approach has received recent criticism – one example being the apparent support for Enterprise Zones. It is imperative that the Coalition responds to these challenges appropriately and efficiently in order to deliver ‘balanced’ and sustainable growth across the UK.

Young graduate location in the UK and the ‘spreading out’ effect

The UK’s young graduates are overwhelmingly located in London and the South East, with approximately 35 per cent living there. They are highly mobile, and traditionally migrate to the capital in search of work after they graduate. London also has the highest graduate retention rate in the country – it not only contains the most universities and the most students, but, most importantly, the most knowledge intensive private sector employment opportunities.

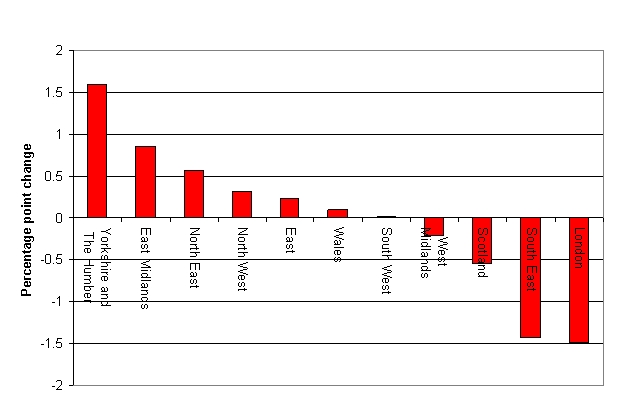

However, in recent years the location decisions of young graduates have begun to change and there has been a ‘spreading out’ effect. Regions such as Yorkshire and Humberside and the North East have increased their national share, whilst regions in the South have experienced a decrease (see figure 1). Cities such as Sheffield and Leeds have seen the biggest relative gains.

Figure 1: Percentage point change in young graduate distribution 2001-09

Source: Annual Population Survey (2009); Local Area Labour Force Survey (2001)

Unlike the United States where graduate retention is strongly associated with the presence of high calibre universities, it is the level of employer demand that has the strongest effect in the UK. The public sector has allowed certain cities to retain graduates in recent years even though private sector demand for high level skills has been weak.

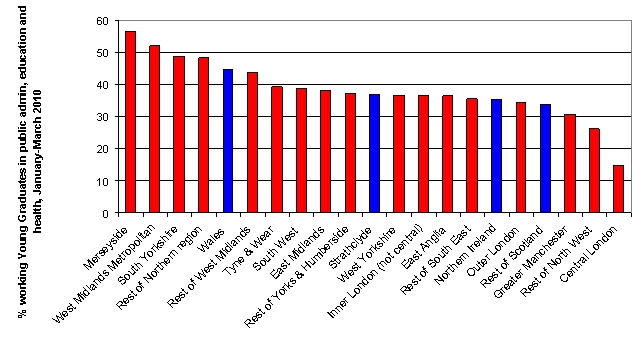

The public sector is now the most common employment destination for young graduates in the UK, and they are disproportionately employed in the public sector outside of the South East. Around 50 per cent of young graduates work in former industrial areas like South Yorkshire, compared to 15 per cent in Central London (see figure 2). However, graduate destination data has shown that approximately 50 per cent of the public sector jobs that new graduates enter straight after graduating can be considered ‘non-ring-fenced’ – the jobs most likely to be affected by cuts.

Figure 2: Public sector employment as a proportion of young graduates, 2010

Source: Quarterly Labour Force Survey, January-March 2010

The short and long term implications of public sector cuts

The Office for Budget Responsibility has forecast that 330,000 public sector jobs will be lost over the next four years as a result of the £81 billion of public sector cuts. This will have two sets of implications for young graduates:

- In the short term there is likely to be an increase in youth unemployment – especially young graduate unemployment. The unemployment rate for new graduates has doubled since the onset of recession to over 20 per cent and a young person is now two and a half times more likely to be unemployed. These are unprecedented levels. The Coalition’s decision to abolish the Future Jobs Fund – a six month paid work placement for under 25s – at this time has received heavy criticism.

- The longer term implications could be more problematic. If the public sector has sustained jobs for talented people in certain regions, there could be a ‘flight’ of highly skilled, highly mobile, young people to London and the South East in search of knowledge intensive private sector employment opportunities. These places would prosper from the in-migration of young graduates at the expense of the public sector dependent cities.

The ‘clustering’ of talented people has many local economic benefits. Places that have more talented people experience more innovation and higher economic growth. Even the lower skilled benefit from the presence of highly skilled individuals as they create more jobs for the local economy. Graduate retention is therefore very important. If those places that have experienced a growing share of young graduates in recent years lose them to other cities and regions, regional disparities will continue to grow in the UK.

Re-thinking policy

The government believes that this agenda is best taken forward ‘locally’. The new Local Enterprise Partnerships are expected to bridge the gap between local authorities and business and bid for the £1.4 billion Regional Growth Fund. However, these new arrangements have limited power and the Regional Growth Fund budget is far less than that of the Regional Development Agencies. Osborne’s other flagship regional enterprise policy – the National Insurance Contributions holiday for new start ups outside of the South East – has also had limited success. The Federation for Small Business has argued that this policy must be extended to existing businesses if it is to have a significant impact.

The government is also likely to reintroduce Enterprise Zones. However, a new report by The Work Foundation has warned against this – they were not only costly, but also tended to displace jobs from the local area. Each new job created cost around £50,000 in today’s money. This contrasts with £6,500 for every new job created by the Future Jobs Fund which was abolished.

Given that public finances are severely constrained it is essential that the right policies are implemented to stimulate enterprise and promote local growth. It may be more useful to put more money into the Regional Growth Fund so that local areas can come up with local solutions to their specific challenges. And local institutions need real power over planning and infrastructure to fully address these challenges.

Lastly, education institutions such as universities and colleges have a key role to play. They not only have the task of providing graduates with the skills necessary to participate in a more innovative and entrepreneurial economy, but should build on their links with local businesses, and find ways of becoming more accessible – providing employment pathways for students. The incubation and commercialisation of innovative ideas in universities must also be supported.

Failure to make appropriate interventions has the potential to exacerbate record levels of youth unemployment and growing regional divides in the UK.

Jonathan Wright regularly writes for The Work Foundation’s blog.

The Work Foundation is an independent authority on work and its future. It aims to improve the quality of working life and the effectiveness of organisations by equipping leaders, policymakers and opinion-formers with evidence, advice, new thinking and networks. For further reading, please see The Work Foundation’s reports on graduate skills and the geography of the recovery.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.