The recent census shows that renting is becoming the norm in urban areas across England. Pete Jefferys explores the implications of this trend, suggesting that it looks set to continue for the foreseeable future. This will have important consequences for voting, community and consumption.

The recent census shows that renting is becoming the norm in urban areas across England. Pete Jefferys explores the implications of this trend, suggesting that it looks set to continue for the foreseeable future. This will have important consequences for voting, community and consumption.

What’s the image that comes to your mind when you think of a private renter? For many people, I suspect they will think of a Londoner – a young-professional, a student or perhaps a family on a low income in Newham or Tower Hamlets. However, the latest statistics from the Census show that renting is fast becoming the norm in urban areas across England, not just the capital.

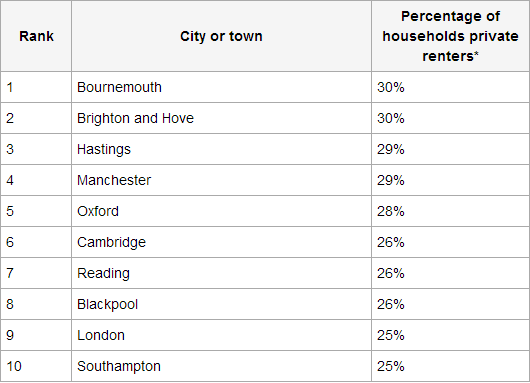

London has certainly seen a big increase in private renters – up to over a quarter of the city’s population in 2011. However it’s not the city with the biggest proportion of private renters in England, in fact it’s only 9th.

Why does it matter what proportion of a city or town rents privately? It’s interesting to see how big the private renting population is in coastal towns, especially in areas such as the north west and south east not often associated with private renting. Student populations – especially in Oxford and Cambridge – go some way to explaining the rankings. However the latest English Housing Survey reveals that less than 6% of private renters are in full-time education compared to 70% in full or part time work. Renters are ordinary working families, often in their 30s and even older.

- Voting and elections: Large renting populations will impact on city and local politics. We know that renters are often young, aspirational families locked out of home ownership. While they are less likely to vote than home owners, the sheer growth of the renting population should make local politicians alert to the problems facing renters and potential solutions.

- Community: Due to short contracts and rising rents, renters are much more likely to move each year compared to those owning a home with a mortgage. This makes it harder for renters to put down roots, leading to decreased levels of social engagement, as measured by volunteering rates.

- High street spending: High rents are sucking consumer demand out of the economy. This means that towns and cities with big renting populations will experience even more pressure on their local high streets. With more and more disposable income sunk into housing costs, this trend should worry small business owners.

The trend towards big renting populations in England’s urban areas looks set to continue, as house prices remain high, lending tight and population growth ahead of house building. According to Savills the rise in renting has been huge in some non-London urban areas over the last decade. In Manchester, the number of households renting has increased 95% since 2001. In Liverpool it was 79%, in Birmingham 75%.

Sustaining anything like this level of growth over the next ten years would mean a profound shift in the make up of urban England. It would have major implications for society, for the economy and for politics, and not just in London.

This post originally appeared on Shelter’s Policy Blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Pete Jefferys is Assistant Policy Officer at Shelter. To find out more about Shelter see their website and Twitter feed.

1 Comments