Rising income inequality has been a key criticism during protests such as the ‘Occupy’ movement, but it is unclear how such criticisms affect voting behaviour. Florence Bouvet and Sharmila King test the extent to which voters have penalised incumbent governments for increases in income inequality and unemployment, both before and after the start of the economic crisis. They find that while a rise in unemployment is strongly linked to a decrease in support for incumbent parties, there is no evidence that voters have penalised incumbents for rises in income inequality. This suggests that citizens might conceive of some economic problems as an ‘exogenous shock’ which their governments cannot be held entirely accountable for.

Rising income inequality has been a key criticism during protests such as the ‘Occupy’ movement, but it is unclear how such criticisms affect voting behaviour. Florence Bouvet and Sharmila King test the extent to which voters have penalised incumbent governments for increases in income inequality and unemployment, both before and after the start of the economic crisis. They find that while a rise in unemployment is strongly linked to a decrease in support for incumbent parties, there is no evidence that voters have penalised incumbents for rises in income inequality. This suggests that citizens might conceive of some economic problems as an ‘exogenous shock’ which their governments cannot be held entirely accountable for.

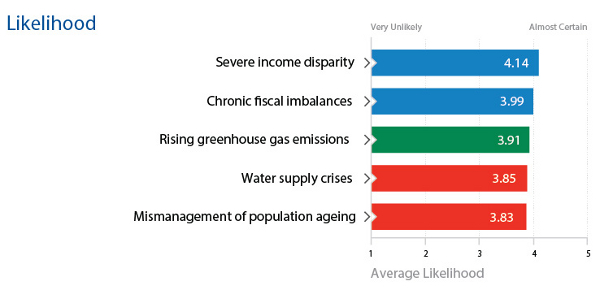

There has been general increasing dissatisfaction with the growing income gap between the rich and poor in Western countries. In a recent study conducted by the World Economic Forum in 2013 (Figure 1), severe income inequality is now ranked as the most likely risk facing the world.

Figure 1: Top five global risks by likelihood

Source: World Economic Forum

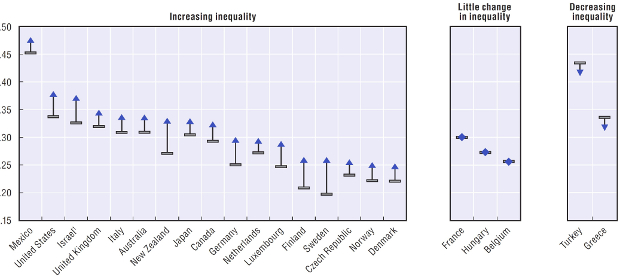

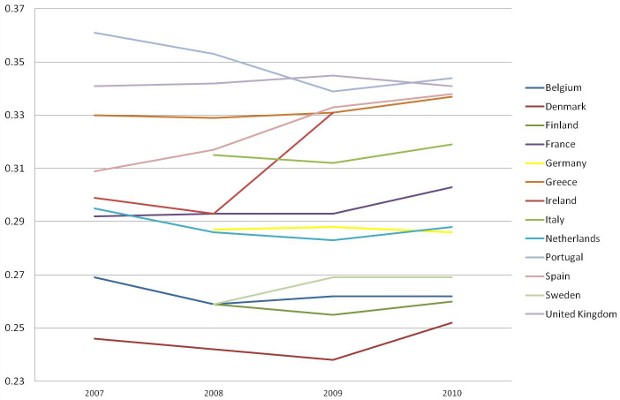

While most OECD countries experienced increases in income inequality in the two decades preceding the Great Recession (Figure 2), rising income inequality during the 1990s and early 2000s was not an electoral issue in most developed economies simply because national economies were growing rapidly. The 2008-2009 Great Recession brought this issue back to the forefront of public debate, even though income inequality generally decreased during the first two years of the economic crisis, as richer households experienced a more dramatic drop in their earnings and investment incomes than the rest of the population (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Income inequality in OECD countries (1985-2008)

Notes: The graph shows Gini coefficients of income inequality for each country. The rectangular bar indicates the value in each country in 1985, while the arrow/dot indicates the value in 2008. An upward arrow therefore represents an increase in income inequality over the period, while a downward arrow represents a drop in inequality. Source: OECD

Figure 3: Recent changes in Gini coefficient, selected OECD countries

Notes: The graph shows Gini coefficients from 2007-2010 (at disposable income, post taxes and transfers). Source: OECD

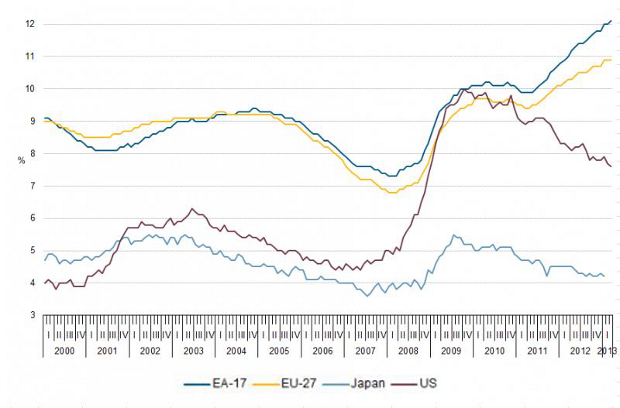

One example of the dissatisfaction among the electorate is the “Occupy Wall Street” protests that emerged from the recent US banking and financial crisis. While the “Occupy” movement in the U.S. has lost some of its momentum with the country’s economic recovery, new protests have emerged in Europe with the sovereign debt crisis. Austerity measures undertaken notably in Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain to qualify for bailout funds from the Troika (European Commission, ECB, and IMF) have led to cuts in government redistributive policies, which in some peripheral European countries (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) triggered an increase in unemployment and income inequality (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Unemployment rates in the European Union, the United States, and Japan

Source: Eurostat

Did the growing dissatisfaction with income inequality and rising unemployment observed on the streets manifest itself on election days? Since 2008, out of the 35 parliamentary elections that were held in the 27 OECD countries, only 8 incumbent leading parties have remained the first parties in their respective national governments. On one hand, the extensive literature on economic voting finds that poor economic development, such as rising unemployment rates, reduce the vote shares of incumbents. On the other hand, the severity and global dimension of the crisis “severely challenged the capacity of governments to steer the national economy”, and thus, could limit the extent to which voters hold incumbent governments accountable for poor national economic outcomes. We use data on parliamentary elections in 27 OECD countries between 1975 and 2012 to examine whether the recent economic crisis induced a shift in economic voting and the relevance of income inequality.

We find that the unemployment rate is the most robust element in economic voting, before and after the crisis. Before 2008, a 1 percentage point increase in unemployment is associated with a 0.98 percentage point decrease in the vote share for the government parties. Following the recent economic crisis, voters held incumbent governments even more accountable for increases in unemployment. A 1 percentage point increase in unemployment is now associated with a 12 percentage point decrease in vote share for all the parties in the incumbent government.

As for income inequality, we find prior to the recent economic downturn a change in income inequality is negatively associated with the total vote share of government parties: a 1 percentage point increase or 1 unit in the Gini coefficient (which is a 3.2 per cent increase) is associated with a 1.2 percentage point decrease (equivalent to a 3 per cent decrease) in vote share. For the period starting in 2008, we find that a 1 percentage point increase or 1 unit increase in inequality, everything else constant, is associated with an increase by 8.6 percentage points in the vote share of government parties. Consequently, voters have not been penalising incumbent governments for rising income inequality. As suggested by Palmer and Whitten, “during periods of severe economic crisis… economic voting might be attenuated as a result of voters discounting the economic outcomes as being disconnected from past policy choices”.

Overall, we find that the economic downturn might have augmented economic voting in terms of unemployment and economic growth by heightening the salience of these issues, since this recession is one of the most severe economic downturns these countries have experienced since WWII. Our analysis suggests that voters did not discount the recent economic crisis as a completely exogenous shock, since they held incumbent governments more accountable for the deterioration in national labour market conditions. Yet, voters acknowledge that international economic interdependence potentially undermines the efficiency and efficacy of domestic stabilisation policies. This result suggests that a severe economic crisis does not necessarily result in voters removing an incumbent party from office.

*The countries in which incumbent leading parties have remained the first parties in their respective governments are: Canada in 2011, Chile in 2009, Greece in 2012, Japan in 2009, Mexico in 2009 (but then lost in 2012), Netherlands in 2012, Turkey in 2011, and the United States in 2012.

A longer discussion of the topic covered in this article is available in the following paper.

This article was originally published on LSE’s EUROPP blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/11Y0rrS

_________________________________

Florence Bouvet – Sonoma State University

Florence Bouvet – Sonoma State University

Florence Bouvet is Associate Professor in the Department of Economics at Sonoma State University. Her research interests include Political economy of EU regional policy, Regional income inequality, and EU regional labour markets.

–

Sharmila King – University of the Pacific

Sharmila King – University of the Pacific

Sharmila King is Associate Professor of Economics at the University of the Pacific, California. Her research interests include monetary and macroeconomics, and international finance. She co-edits the book International Economics, Globalization, and Policy: A Reader (McGraw-Hill).