Social “immobility” and higher inequality are a cancer more pervasive than anything we have experienced in the last few decades, write Terence Tse and Mark Esposito. The need to open up opportunities to those from disadvantaged backgrounds may be more important than before.

One of the most staggering collaterals of the financial crisis, globally but particularly so in Europe, has been the increase of inequality across social fabrics, as we previously outlined in relation to the US.

As attention was being narrowed to a more micro level, bearing in mind the state of mobility and recruitment, we argued that résumés are messing up recruiting. This is because these curricular vitae lead recruiters to put disproportional emphasis on skills, work experience and schools attended, rather than on what truly counts such as the applicants’ behaviour, work ethic or ability to fit into a company’s culture. And these are all arguably more important qualities of good managers. But with HR managers placing too much attention on previous work experience and schooling can come a huge social cost: such common recruitment practices tend to favour those people from well-off families. These families often have strong ties with prestigious employers, making it more likely for their children to be placed there. They are more likely to be able to afford private education, which has often shown itself to be a passport to good jobs.

In short, the current employment practices give applicants from wealthy backgrounds some distinct advantages.While the above can be seen as part of a global phenomenon, the situation in Europe is probably among the most worrisome. Quality jobs rarely reach the lower echelons of our societies, pervasively supporting our concern about poor mobility across the social spectrum of labour and its productivity.

This latter is a necessary determinant for the revival of the European economy and its competitiveness, but of course, it is nothing new. Throughout human history, good opportunities all too often circulate only among the privileged. However, in view of the recent debate on income inequality, the need to open up opportunities to those from disadvantaged backgrounds may be more important than before. But sadly, recent observations suggest that the on-going trend of the well-off taking most of the good jobs is likely to continue. If we take a recent report published by the UK’s Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission for example, it paints a very bleak picture when it finds that top employers recruit from only about 20 – effectively the top 20 – out of more than 115 universities in the country. The report further points out that 65 per cent of the respondents surveyed think “who you know” is more important than “what you know”. Equally telling is that 75 per cent of them believe backgrounds of the family play a critical role on life chances in the UK today.

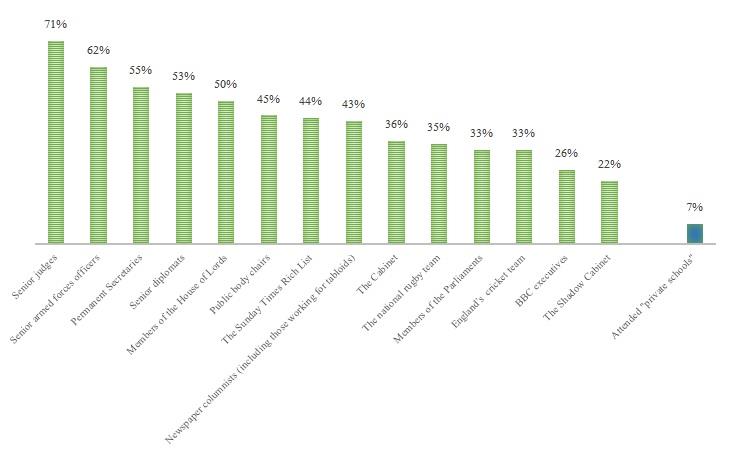

In other words, income earned by the parents can hinder or hasten children’s abilities to climb the society ladder. Birth, or what is also called the “lottery by birth”, and therefore not merit, is in many instances the key determinant of life chances. Perhaps the most telling example of all is the relationship between private education and chances to succeed in life. In Britain, it has been found that those who went to private schools earned 7 per cent more than their peers. This is even so when they went to the same universities to study the same subjects and received the same degree class. Some 7 per cent of the UK’s children attend private schools. Yet, they account for a disproportionate number of what are considered the best jobs in Britain.

The same also appears to be happening in France. Despite its epic motto, “liberté, égalité, fraternité”, corporate France is ran by graduates of the “Grandes Écoles” and “Polytechniques”, as a recent study points out. On the surface, this may be a good thing because graduates from these schools are often of the highest quality in the country churning out talented graduates. Yet, the problem is that those schools favour those who come from well-off or well-educated families. The reason: in order to get into these top schools, students would need to go through a set of very vigorous examinations, which children from more well-off families are more ready to take on. Furthermore, since many executives from top companies as well as high-ranking politicians are products of those establishments, work and networking opportunities are often self-perpetuating among the elites.

What is worrying about these findings are not just their sheer proportions, which are a sign of defective social mobility process, but that pretty much every key domain, be it politics, media, business or the public sector, are run by those who can “afford” it. The lack of opportunities for people from the lower income groups to move up also reflects elitism in the same way as the lower “casts” are deprived of the opportunity to prosper.

What we find even more troubling is the complete absence of social mobility from the Youth Guarantee Scheme, which has been rolled out by the European Commission, with the aim of tackling youth unemployment. While the scheme by itself has the noble purpose of allowing people to find employment, within 4 months from the end of a formal educational cycle, it assumes that merit, not status or family ties, will determine the access to labour. This oversimplification may cause unfair employment opportunities, reinforcing even more the disparity of opportunities.

Breaking the well-offs from holding their grip on the top of society and improving social mobility is difficult and the social debate in Europe is not necessarily capturing this shade of grey, which seems to have slipped from media attention, preoccupied as it is mainly by unemployment statistics.

To corroborate the issue as we have presented it, there is the further problem of “downward mobility”. A recent study in the UK points out that with the growth rate of professional employment decelerating, children from well-off families find it more difficult to achieve the same levels of standard of living as their parents. With downward mobility becoming increasingly common, it is likely that upward mobility would come under further pressure.

As impossible as the mission of improving social mobility may sound, we do not really have another alternative because the current impasse is so structurally entangled that the entire social system risks a deadlock . Social “immobility” and higher inequality are a cancer more pervasive than anything we have experienced in the last few decades. The inability to break with the current ill-conceived and ill-evolved system will not result in just an exacerbation of the situation in the way we are experiencing it today; it may also lead to social revolt and upheavals that our future generations will have to face. With so much at stake, we can no longer ignore the problem.

Note: This article was originally published on the LSE’s Euro Crisis in the Press blog and gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Featured image credit:

Mark Esposito is an Associate Professor of Business & Economics at Grenoble Graduate School of Business in France, an Instructor at Harvard Extension School, and a Senior Associate at the University of Cambridge-CPSL in the UK. He serves as Institutes Council Co-Leader, at the Microeconomics of Competitiveness program (MOC) at the Institute of Strategy and Competitiveness, at Harvard Business School. Mark is the Founding Director of the Lab-Center for Competitiveness. His full profile can be found at www.mark-esposito.com and he tweets as @Exp_Mark.

Terence Tse is Associate Professor in Finance at the London campus of ESCP Europe Business School. He is also the Head of Competitiveness Studies of i7 Institute for Innovation and Competitiveness, an academic think-tank. He can be reached at terencetse.com and @terencecmtse on Twitter.

Dear Terence Tse and Mark Esposito,

For me, locally and our national economy, social mobility is an important factor that doesn’t only represent a singular momentum of Upwards achievement, but also a collective approach towards how small business – and those running it – can help to trigger a motivation and inspiration amid the challenges faced by many.

However, let us also be strong and unforgiving of the political policy making that have been responsible for failed policies – in particular, business start-up schemes engineered by central government and partnered with banks – that many times failed those it was meant to be supporting. Those who were most probably unable to rebuild their lives again after such losses.

It’s clear that many things have to be mentioned so that we don’t repeat past mistakes. It’s also clear that BEST Attitude needs to be at the heart of policy that is willing to ‘protect’ those it fails, and help to improve those ideas and skills it has been responsible for harnessing.

The Work Programme is a policy that desperately needed to work for those on ESA benefits. But, did it achieve its goal?

Sadly, the terms “shirkers’ and ‘skivers’ has played a significant part in hindering those even further as they continue to be failed by a Work Programme that has a narrow remit when it comes to employer engagement. Many may feel that it is odd to suggest that because one is not working – including those failed by a recession and the homelessness and business losses that many well have followed – are those who are willing to accept a job working for Tesco, KFC… etc. Now, there’s nothing wrong with such jobs. However, with a diversity of skills base in the number of unemployed people – post recession – let me suggest that such a diversity of skills needed to be matched by a diversity of solution by government and WP contractors. Now, where was this ‘tight ship’ in the form of policy and practice in reflection of such a demand in desperate need of utilising their skills?

Post recession demanded that policy makers were in acknowledgement of the failings, challenges, aspirations and A Fight to Achieve social mobility goals by those now unemployed. But, let us not use the term unemployed – as it signifies an unfair, pseudo reflection of the proactive stance that JOB SEEKERS have taken amid the challenges they have faced.

As someone who have felt the strong arm of poor policy making decisions, I am appalled at their weaknesses and seemingly inability to connect with individuals like myself who have remained both Resilient and Creative throughout my journey towards ‘getting back on my feet’, achieving employment goals and continually thinking BIG as I write business plans.

It is my view, something is missing in our communities. So many Charities, social enterprises and community interest companies, but yet… an echo continues to bounce of the walls of these organisations as the VOICES of many – including, myself – remain silent.

HARNESSING the Voices of those who feel Disconnected – though Proactively still Fighting towards a professional goal – has to be a KEY element of community organisations. Though, in my experience, such a policy and practice remains as weak as the Work Programme. Yes, that may sound tough to say or to read, but real as it remains a hindering factor in causation, and its effective does more to enhance MENTAL HEALTH challenges.

So, finally…. who is really listening, who really cares and who will respond to the important points I have made? That, will speak volumes!

All the best!

Ivor