In the run up to the AV referendum in May, there has been considerable debate and commentary from both campaigns on how AV would actually operate. In this light, it is worth considering the impact of the last large-scale electoral reform in the UK: the 2007 introduction of another preferential electoral system, the single transferable vote (STV) for local government elections in Scotland. Alistair Clark looks at what this change can teach us about what may happen if the ‘Yes’ campaign is successful.

In the run up to the AV referendum in May, there has been considerable debate and commentary from both campaigns on how AV would actually operate. In this light, it is worth considering the impact of the last large-scale electoral reform in the UK: the 2007 introduction of another preferential electoral system, the single transferable vote (STV) for local government elections in Scotland. Alistair Clark looks at what this change can teach us about what may happen if the ‘Yes’ campaign is successful.

When STV was introduced for Scottish local government elections in 2007, it was the first large-scale use of STV on the mainland for many decades. The effects of STV have been variously referred to as a ‘quiet revolution’ or as a ‘transformation of local politics’, with Scottish councils becoming more proportional, and voters adapting to the new electoral system with relative ease. On the other hand, however political parties adapted relatively poorly to the new system, with most parties failing to offer enough candidates to optimise their campaigns under STV.

The shift necessitated a large-scale redistricting exercise to introduce the multi-member wards needed by STV. Scotland moved from electing 1,222 councillors to 32 unitary councils from first-past-the-post wards, to electing the same number of councillors from just 353 new multi-member wards. These wards elect either three or four members per ward, 190 electing three councillors, 163 electing four. The low number of members per ward, at least initially, seemed to suggest that while STV would be more proportional, this proportionality might be limited.

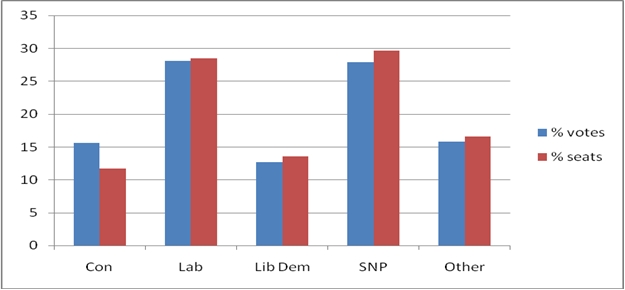

The headline results saw a dramatic change in the composition of Scottish local government. Labour lost a large number of councillors, falling from 509 in 2003 to 348 in 2007. This seems dramatic, but Labour had been in gradual decline in Scottish local government for some time with STV merely accelerating this trend. In terms of councillors, the largest party post-2007 became the Scottish National Party (SNP), doubling its representation from 181 in 2003, to 363 in 2007. Figure 1 assesses the outcome, charting the proportion of first preference votes to seats won. From this we see a relatively proportional picture: Labour winning 28 per cent of first preferences and 29 per cent of seats and the SNP winning 28 per cent of first preferences and 30 per cent of council seats. While there is evidence that small parties struggled to be elected in the new multi-member constituencies even for the ‘others’ the result is largely proportional, boosted by Scotland’s tradition of Independent politics in the Highlands and Islands.

Figure 1: Proportionality 2007 STV Scottish local government elections

So how did the voters adapt to the new system? Since the 2007 local elections were concurrent with the Scottish parliament elections held under the AMS/MMP electoral system, voters were faced with a complex set of ballot papers and voting decisions. The evidence is that they dealt with STV well, at least in a comparable way to both parts of Ireland. The proportion of rejected ballot papers was just under 2 per cent (0.77 per cent in 2003), but this was considerably fewer than for the concurrent Scottish parliament election (at 4 per cent) and appeared reasonable given levels of rejected ballots under STV elsewhere. The average number of preferences used by voters was 3.04, and this level appeared remarkably consistent across a number of ballot paper and candidate configurations. There was also ample evidence of ballot position effects, examined from a variety of perspectives.

Three-fifths of candidates were elected with the help of preference transfers or voters using their preferences to choose two candidates from the same or different parties. Where these transfers were between two candidates of the same party, the message is that standing more than one candidate in a ward can be rewarded by voters. Where parties did so, there were relatively low levels of voters using their first preference only (or non-transferable votes), and second preferences overwhelmingly went to co-partisans. This reached 66-70 per cent for Labour and the SNP, but the point holds across all four main parties.

With transfers between parties, otherwise called ‘split-ticket voting’, where parties did not stand more than one candidate, there is evidence of second preference transfers across the main centre-left parties i.e. Labour, the SNP and Liberal Democrats. The Conservatives look somewhat isolated here, with the lowest level of second preference transfers of all four main parties. This to some degree explains the disparity between votes and seats for the party (shown in Figure 1) – Conservative candidates did not attract large transfers thereby restricting their electability.

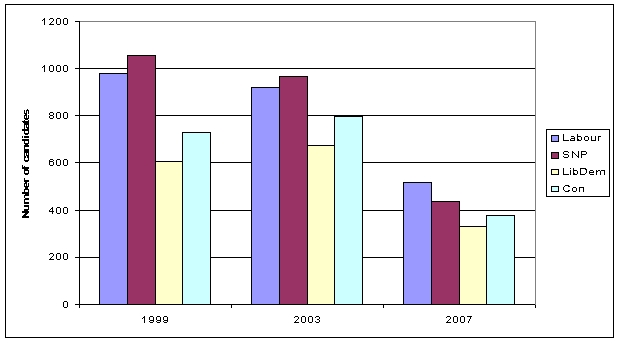

In terms of campaigns and candidate strategies, the first thing that the smaller number of wards did was ease the pressure on party organisations to recruit enough candidates to offer a candidate in each ward. Thus, as Figure 2 shows, the total number of candidates contesting the 2007 elections fell considerably, from a record high of 4,195 in 2003 to 2,607 in 2007.

Figure 2: Main party council candidates, 1999-2007

Sources: Denver and Bochel, 2000; Bochel and Denver, 2004; Clark, 2005.

Campaigning under STV was complicated by the concurrent Scottish parliament elections, and local party organisations saw the STV elections as a ‘second order’ priority. Parties tended not to take the opportunity to run ‘teams’ of candidates. The only party to do so was Labour, offering more than one candidate in 51 per cent of wards. Otherwise, the dominant candidate strategy for the main parties was to offer only one candidate per ward, with 81 per cent of wards only having one Conservative candidate, and between 60-67 per cent of wards for the Liberal Democrats and SNP. Where parties did stand more than one candidate, they often adapted well to campaigning under STV, with some good examples of ‘vote management’ efforts for all parties, not least Labour in Glasgow. However, it is clear that parties were largely feeling their way with the new system, seldom having any data on potential transfer preferences and candidate loyalties needed to maximise their efforts under STV. Nor did parties advise voters to use their preferences for potential post-election coalition partners.

What have we learned from the use of STV in 2007? Three things in short. Firstly, the outcome was relatively proportional and has made a dramatic change to the composition of Scottish council chambers. Most importantly, voters adapted well to preferential voting, using it in a way comparable with practice in both parts of Ireland where experience with STV is much more extensive. So STV can be said to have led to a transformation in Scottish local politics and also in how voters cast their vote. However, parties adapted less well, failing to clearly exploit the opportunities offered by preferential voting. This suggests that under any new electoral system party campaigns will take time to find their feet and maximise their potential.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.