Alistair Clark analyses the recent Scottish local government elections and makes the case for the single tranferable vote (STV) system. Contrary to the arguments drawn by its opponents, Clark finds the system does not lower turnout, nor does it lead to a greater rejection of ballots. While there is a correlation between an increased ballot position and votes received, this result is not confined to STV.

Alistair Clark analyses the recent Scottish local government elections and makes the case for the single tranferable vote (STV) system. Contrary to the arguments drawn by its opponents, Clark finds the system does not lower turnout, nor does it lead to a greater rejection of ballots. While there is a correlation between an increased ballot position and votes received, this result is not confined to STV.

The introduction of the single transferable vote (STV) for Scottish local government elections remains highly controversial, with some suggesting the system’s complexity is off-putting for voters. Research into the 2007 local elections, the first time that STV had been used on the British mainland in many decades, challenged this view.

The 2012 round provides a clearer indication of how STV has impacted upon political behaviour because these were run as stand-alone elections and not concurrently with Scottish parliamentary elections as in 2007. Alongside an account of the campaign and the results, I examine party and voter behaviour more fully in my forthcoming Representation article ‘Second Time Lucky? The Continuing Adaptation of Parties and Voters to the Single Transferable Vote in Scotland’. On the basis of aggregate ward-level results from 2012, here I seek to deal with some of the controversies about how voters have used STV.

The first claim often made is that the use of STV in 2012 led to low turnout. While turnout did drop from 53.8% in 2007 to 39.8%, it is important to recognise that this had nothing to do with the electoral system. Turnout dropped because the 2007 local elections were held concurrently with those to the Scottish parliament. Consequently, it was inevitable that turnout would be higher in 2007 as most people were mobilised by the need to also cast a ballot for the Holyrood contest. In 2012, the local elections were changed to become a stand-alone contest, largely as a consequence of the large numbers of Scottish parliamentary ballot papers that were rejected in 2007 (a fiasco which was in itself not caused by STV). Held on their own, the local elections were always likely to have lower turnout, with some predictions even as low as the mid-20% range. The eventual 39.8% turnout was higher than had been expected in some quarters, with around a quarter of those voting casting a postal ballot.

Scottish turnout also compares favourably with the English local elections held on the same day where, according to the Electoral Commission, turnout was 31.1% and 29% in the concurrent Mayoral Referendums. Comparative research has shown that electoral systems per se are neither responsible for increasing or decreasing turnout, whatever the proponents and opponents of various systems might argue. The introduction of STV itself has not therefore impacted upon turnout. Instead, a myriad of other complex factors are at play including social inclusion/exclusion, and the willingness of parties to get out and run active campaigns. Moreover, during the 2012 local elections many Scottish councils appear to have gone out of their way to restrict the amount of publicly displayed campaign literature – posters etc – from parties, hardly a good way of publicising an election.

One very important indicator of whether or not voters have understood an electoral system is the amount of rejected ballots that it produces. In this regard, Scottish STV compares well with the system’s use elsewhere. In total, only 1.7% (27, 046) of ballots were rejected, slightly lower than the 1.83% (38,351) rejected in 2007. By contrast, the 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly and local government elections, both conducted using STV, had respectively 1.84 and 2% of ballots rejected despite having an electorate and parties much more used to preferential STV voting. On this measure, Scotland’s voters compare well.

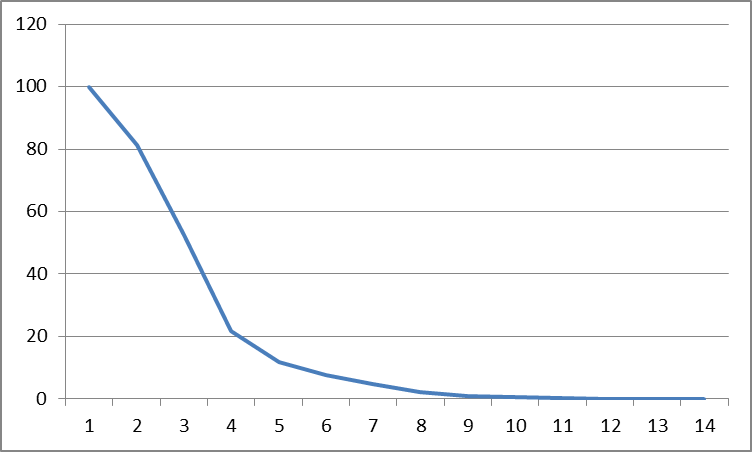

Figure 1: Preference usage, 2012

This notwithstanding, if voters choose to only cast one preference, as permitted by the Scottish system, the preferential nature of STV is largely defeated. This means that patterns of preference usage are a further important indicator. Denver, Clark and Bennie (2009) showed that in the 2007 round of STV elections, 78% cast a second preference and 54% cast a third preference. As figure 1 shows, such a pattern was also evident in 2012; 81.3% of voters understood the system well enough to cast a second preference, and 52.6% cast a third preference. Research on Ireland suggests that voters casting around three preferences under STV is normal. In this regard, Scottish voters perform as might be expected. Some voters go further with, at the extreme, a small number of dedicated people completing every preference on the ballot paper.

The multi-member wards used for STV mean that, where parties feel they have the support, they can offer multiple candidates in an attempt to maximise their number of elected representatives. Only Labour and the SNP have engaged comprehensively with such campaign strategies however. In 48% of wards in 2012, voters could choose from two or more Labour candidates. The SNP were criticised in 2007 for not running enough candidates to optimise their outcomes. This was rectified in 2012 with numbers of Nationalist candidates rising from 437 to 613. This meant that voters could choose from two or more SNP candidates in almost 70% of wards. The dominant candidate strategy for the other parties was to offer just one candidate per ward.

This means that there are two potential patterns of vote transfers to assess: intra-party transfers, where parties offered more than one candidate per ward; and inter-party transfers where parties offer only one candidate. 2012 provides some key findings in this regard. Firstly, where parties offered more than one candidate, levels of non-transferable votes were much lower (between 5.9 – 7.8%) than where parties only offered one candidate per ward (15.9 – 30.3%).

Secondly, levels of transfer solidarity where parties offered more than one candidate were high, above 69% for the Conservatives, 75% for the SNP and peaking at 77% for Labour. These levels of transfer solidarity are comparable with Irish elections under PR-STV.

Thirdly, where parties offer only one candidate per ward, there are transfers between all party options. Notable was the 21% of Labour transfers which went to the SNP, with only 13% going in the SNP-Labour direction. There is little evidence here of most voters not understanding the potential of the system to vote for both parties and candidates.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of STV has been the potential for ballot position effects where those higher on the ballot paper achieve higher levels of first preferences than those lower down. These effects were found in 2007, and the Scottish government undertook a consultation into the issue before deciding to retain alphabetical ordering. In 2012, there was also a relationship between position on the ballot paper and the number of first preference votes achieved. The bivariate correlation coefficient between ballot paper position and number of first preference votes achieved was -.200, while, measured another way, the eta measure of association was .216. Both results were statistically significant, indicating that this relationship is more than just a chance effect.

It is important however not to dismiss STV outright because of this effect. Firstly, although rough aggregate measures, these results indicate relatively weak correlations between ballot position and the number of first preferences received. In other words, while there may be an aggregate pattern to this, it is nevertheless not an inevitable outcome. Indeed, more active campaigns or other measures by candidates and parties might serve to counter this.

Secondly, critics appear under a misapprehension that STV is the only electoral system in which such effects are present. This is mistaken. Other electoral systems also suffer from ballot position effects. Recent research on English local elections from 1973-2011 by Webber et al. (2012: 16) has concluded that ‘there is clear evidence of alphabetic bias even for the simplest ballots where only one person is to be elected and where there are very few other candidates’. While this rises with ballot complexity, these elections were primarily conducted under first past the post rules. STV is therefore very far from being the only electoral system with such effects. Consequently, it should not be dismissed on that basis.

The use of STV in Scotland remains controversial in some political quarters even after its second 2012 use to elect Scottish councils. However, Scottish voters used the system as might be expected in 2012, and in a way that shows the system has been understood well enough thanks to public education campaigns and the efforts of polling station workers to remind voters of its preferential nature. The difficulties being associated with it – turnout, rejected ballots, ballot paper effects – are however much bigger questions and not confined to STV. As such they are much less amenable, and much harder to change than continually criticising the electoral system deployed to elect Scottish councils.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Dr. Alistair Clark is Lecturer in Politics at Newcastle University. His research interests revolve around political parties, party organisation, party system change and local politics. Much of his recent research has examined electoral reform and its impact on party campaigns and voting behavior. His book Political Parties in the UK was published by Palgrave in 2012.

2 Comments