The coalition government has promised a ‘rehabilitation revolution’ in our penal system. Last week the Ministry of Justice published its business plan for the next four years, a major part of which focuses directly on reducing historically high re-offending rates. The business plan sets rehabilitation as its first ‘structural reform’ priority, and outlines steps towards a new ‘social impact bond’ (SIB) funding model and ‘payment by results’. Simon Bastow finds that the plans are bold but still sketchy. However, simple low-cost measures such as publicly reporting on individual prisons’ reoffending rates can be an important step in the right direction.

The coalition government has promised a ‘rehabilitation revolution’ in our penal system. Last week the Ministry of Justice published its business plan for the next four years, a major part of which focuses directly on reducing historically high re-offending rates. The business plan sets rehabilitation as its first ‘structural reform’ priority, and outlines steps towards a new ‘social impact bond’ (SIB) funding model and ‘payment by results’. Simon Bastow finds that the plans are bold but still sketchy. However, simple low-cost measures such as publicly reporting on individual prisons’ reoffending rates can be an important step in the right direction.

Rehabilitation elements of our prison system have long been a source of scepticism amongst prison experts and professionals. Since the late 1970s, researchers have pointed to the gradual de-prioritization of rehabilitation as a function of the system. By the early 1980’s, Anthony Bottoms had identified the ‘collapse of the rehabilitative ideal’. More recently, research by Michael Cavadino and James Dignan’s for their 2003 book The Penal System, found a ‘crisis of legitimacy’ based in a loss of confidence in the whole rehabilitative project.

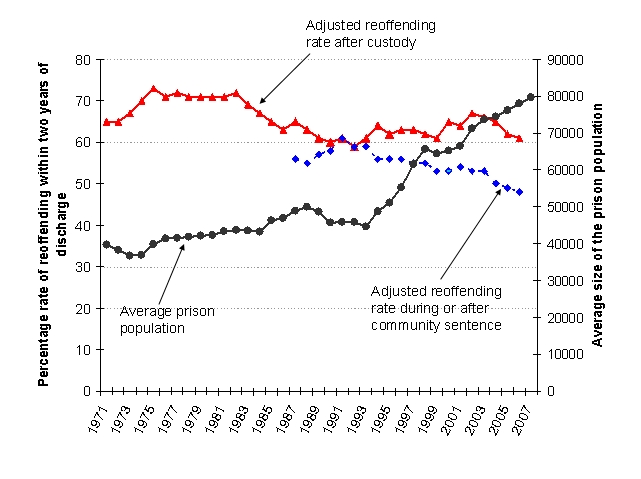

On balance, much of the research in recent years probably overstates the ‘crisis’ theme. Nevertheless, scepticism about the ability of the penal system to reform persists at policy and professional levels. Prisons are perceived as chronically overstretched. Prisoners are commonly discharged without any systematic support once the prison gate has closed behind them. And existing data shows little or no correlation between reoffending rates and interventions by the prison system (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Estimated reoffending rates for custodial and community sentences, 1971 onwards

Source: Ministry of Justice 2010

The shift in emphasis towards rehabilitation and funding programmes which directly contribute to reducing reoffending rates must therefore be seen as quite a radical and bold move by the new coalition.

Social Impact Bonds

At the centre of the ministry’s plans there is an emerging role for social impact bonds (SIB) and growing SIB markets. Under this model, bonds are raised from investments by charitable or commercial organizations. Private or third sector providers then deliver rehabilitation programmes, with payments contingent on the achievement of pre-specified levels of reduction in reoffending rates. No reduction, no payments.

A pilot scheme is currently underway at Peterborough prison and further pilots are envisaged, although the Business Plan is still disappointingly sketchy about the details and expanse of coverage.

It is still early days for SIBs and for evaluating their potential to reduce reoffending. Supporters point out that bonds can provide a sustainable source of long-term funding for the voluntary sector to expand and deepen successful programmes of support for offenders. Sceptics, however, argue that there are likely to be difficulties in scaling up the level of investment in such bonds in order to fund large-scale transformation. A recent BBC Radio 4 programme ‘Analysis’ discusses the pros and cons of this new funding model.

Open Reporting

A small and seemingly trivial innovation may be cause for more quick-win optimism at this stage. For the first time ever, and as part of the sharpening of focus on rehabilitation, government has published reoffending rates for individual prisons. While these data are buried in an Excel spreadsheet on the Ministry of Justice website, they are there for those willing to search.

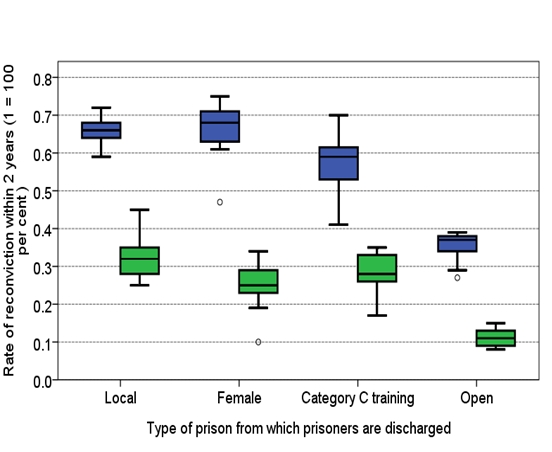

Figure 2 below summarizes some of this data for four different groups of prison. Boxplots differentiate between sentences less than 12 months (blue boxes) and sentences over 12 months (green boxes). The data confirms a well-established structural phenomenon in the prison system that the propensity to reoffend is around twice as high for sentences less than 12 months compared to those over 12 months.

Figure 2: Rates of reoffending within two years after discharge from different types of prison, for sentences less than 12 months (blue boxes) and sentences more than 12 months (green boxes)

Source: Ministry of Justice

Note: Boxes show the interquartile range of points (i.e. all values within 25 per cent to 75 per cent of the range) and tails show the extreme quartiles. The mean value is shown by the thick black line across the boxes.

The sheer lack of variation in the reoffending rate for local prisons, which generally hold short term prisoners on sentences under 12 months, underlines the structural nature of the problem. Local prisons have traditionally been the most crowded and most frenetic in terms of prisoner turnover, and it has almost become conventional wisdom that these prisons are unable to do much more than continually process prisoners in and out on a kind of ‘revolving door’ process.

With the publication of these data, however, prison governors can now be held directly accountable for the quality of rehabilitative services of their prison. This low-cost move could potentially transform the way in which rehabilitation is prioritized across the system – focusing the minds and resources of governors in much the same way that published league tables changed the priorities of headteachers in secondary schools.

Many governors and senior officials will rightly point out that the constant movement of prisoners around the system raises considerable difficulties in assessing the impact of individual prisons on prisoner reoffending rates. For example, if a short-sentence prisoner ends up being moved two or three times in a sentence, which prison should get the blame for his or her reoffending, or the credit for his or her rehabilitation? These are tricky questions that would require proper analysis by the Ministry of Justice – but they are certainly not irresolvable. Governors may also rightly point out that they do already focus on rehabilitation, but are constrained by the pressures of numbers in the system. They probably have a decent case here, However, the systemic effects of making them more responsible for rehabilitation in their own prisons would almost certainly be synergetic with the new-found political emphasis on rehabilitation.

Long-term reform

Of course, improved performance reporting does not in itself constitute a rehabilitation revolution. Many of the problems in the penal system are chronic, and require coordinated work on a number of fronts.

The business plan acknowledges that much will have to be done to reform sentencing practice in order to reduce what is seen as excessive use of prison. This seems sensible. There is still much uncertainty however as it is not the first time that ministers have set out in vain to reshape sentencing behaviour.

The plan also calls for the National Offender Management Service to be restructured. The danger here is that the Ministry of Justice gets distracted by yet another round of national and regional level reorganization, and devotes much of its intellectual and financial resources to fixating on structures, rather than focusing on improving outcomes.

The rehabilitation revolution will depend on a number of major policy shifts and will take time to develop. The development of social impact bonds and bond markets is encouraging. But it will take time for them to change the entrenched cultures and conventional wisdoms which have mitigated against rehabilitation efforts over the years. Open reporting of data on rehabilitation rates in individual prisons, however, may prove to be a simple measure which can help to set the whole system moving in the right direction.

Click here to respond to this post.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

1 Comments