Last Tuesday universities were hit by a second strike as staff walked out over Higher Education pay. Sally Hunt outlines the issues and writes that while pay is a major driver, the deep-seated unhappiness felt by staff has been brought about by more than just falling rates of pay. The job of an academic has become increasingly characterised by unmanageably high workloads, stress and insecurity.

Last Tuesday universities were hit by a second strike as staff walked out over Higher Education pay. Sally Hunt outlines the issues and writes that while pay is a major driver, the deep-seated unhappiness felt by staff has been brought about by more than just falling rates of pay. The job of an academic has become increasingly characterised by unmanageably high workloads, stress and insecurity.

It looks likely that strike action by university staff will continue in the new year. Higher education institutions have been hit by two walk-outs during the autumn term and now my union, the University and College Union (UCU), along with three other unions with members in higher education, is considering plans to escalate the action.

Members of UCU were joined on the picket lines by members of UNISON, Unite and Scottish education union, the EIS. Across the country, our members took action in their thousands resulting in the closure of some institutions and key facilities such as laboratories and libraries, while hundreds of classes, lectures and seminars had to be cancelled. At many institutions, large groups of students turned out to support us and the National Union of Students (NUS) issued a statement supporting the action.

Our industrial action is about pay which has plummeted by an estimated 13% in real terms since October 2008. But while pay is a major driver, the deep-seated unhappiness that many staff now feel has been brought about by more than just falling real-term rates of pay.union, the EIS. Across the country, our members took action in their thousands resulting in the closure of some institutions and key facilities such as laboratories and libraries, while hundreds of classes, lectures and seminars had to be cancelled. At many institutions, large groups of students turned out to support us and the National Union of Students (NUS) issued a statement supporting the action.

The job of an academic has become increasingly characterised by unmanageably high workloads, stress and insecurity. Many UCU members report working a 45 hour-week, then spending most evenings and weekends working at home. The pressure is on to excel at teaching, produce research that is graded as “internationally excellent”, bring money in to the university through fundraising and grant applications, answer all correspondence efficiently, and be constantly available to ever-increasing numbers of students.

Many staff report their working lives have fundamentally transformed since the government begun its all-out drive to marketise higher education. The decision to lift the cap on tuition fees and take away the teaching grant for all but STEM courses has been a massive game-changer for staff.

All these factors have contributed to the very strong and repeated rejection of the 1% pay offer for this academic year. The miserly rise was first rejected by UCU members in June when the union consulted representatives in its workplace-based branches. It was then rejected again in an online survey of UCU members carried out over the summer. Finally, it was rejected in the ballot of members in September that led to the strike action. On each occasion, the majority voting for action increased.

After our first successful strike day on Halloween, the joint unions met with the Universities and Colleges Employers Association (UCEA) for further talks. There was no more money forthcoming and, insultingly, the employers only said they were willing to ‘look into’ any equality issues if members accepted the real-terms pay cut on offer.

We have been repeatedly told by UCEA that there is no more money in the systemand that universities need to maintain a buffer of surpluses and these are currently low. However, longer term forecasts by HEFCE show that surpluses are growing not shrinking.

In English institutions, there is a blip over the next year, when surpluses are due to fall from just over £900m (4.2% of income) to £660m (2.7% of income). However, after that, there is likely to be a longer-term rise. They are forecast to reach £1.1 billion (4.3% of income) by 2015/16 as a result of higher undergraduate tuition fees and international student recruitment.

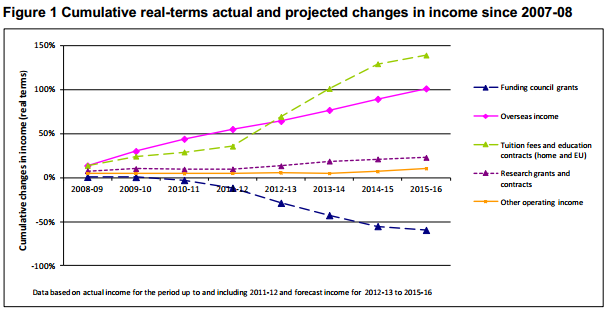

Figure 1 shows the cumulative actual and projected changes in income (excluding endowment income) in real terms since 2007-08. This illustrates a decrease in funding council grants over the period but significant growth in other income streams.

In addition in England, the sector’s discretionary reserves are strong. At the end of 2011/12, they totalled £8,965 million, taking into account pension liabilities (excluding USS) representing 38.5% of income. These reserves are forecast to accumulate to £13,398 million by 2015/16, according to HEFCE.

So we know that our English universities are in very good financial health on the whole. While there may be a one-year dip in surpluses, they are conservatively forecasting a continued accumulation of surpluses and reserves.

The reality is that universities are choosing other priorities – most obviously buildings and senior staff at the expense of everyone else. It’s not possible to quantify expenditure on buildings but our members report building work is ubiquitous on campus. Of course, new buildings and facilities will help to attract students but they are no guarantee of quality of education.

What is equally apparent to staff is that pay and benefits for university leaders is on a strong upwards trajectory. Pay for vice-chancellors increased, on average, by more than £5,000 in 2011/12, with the average pay and pensions package for vice-chancellors hitting almost £250,000.

The gap between those at the top and those at the bottom is stretching. A large number of junior research, administrative and support staff are on poorly paid contracts. Research by the National Union of Students found that 80 higher education institutions pay below the Living Wage to some of their employees, equating to 57% of universities. More than 12,500 employees are paid less than the Living Wage by UK universities. Shockingly, the median lowest wage of staff in UK universities is £7.39 – less than Living Wage.

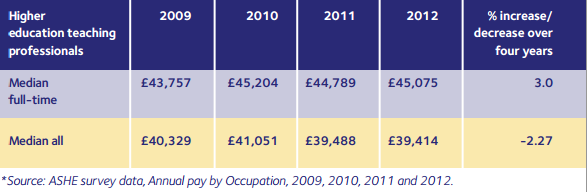

Furthermore, the UCEA claims that higher education pay continues to be competitive in the economy and that median earnings increased by 3.6% in 2011-12. They cite the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) as their source. However, the ASHE data shows that in terms of median full-time pay, higher education teaching professionals have seen pay rise by only 3% in absolute terms since 2009. If part-timers are taken into account (a significant group in our extensively casualised sector) median pay has actually fallen in absolute terms by 2.27% – see Table 1 below.

Table 1

to academic salaries?

The ASHE data can also be used to demonstrate that higher education teaching professionals are still paid significantly below comparably skilled professionals like legal and medical professionals.

UCU expects to communicate detailed plans for further action in the near future. Of course, no one wants to see further disruption and we want to see this dispute resolved. We want to meet with UCEA to negotiate a settlement and are prepared to talk about any new financial package that they wish to propose. In the meantime UCU members will continue their work to contract action which means they are sticking to their contracted hours and not carrying out any voluntary duties.

Without successful negotiations universities can expect more disruption. Will Hutton recently described the suppression of academic pay that as one the most sustained cut in wages since the Second World War.

What is clear in this dispute is that many staff who have a strongly-held belief in a fair, well-funded university system believe four years of wage suppression in a context of increasing marketisation is unacceptable. Their goodwill is in short supply, they are determined to be heard, and they have a resolve to see this through.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Sally Hunt is general secretary of the University and College Union (UCU) – the world’s largest post-16 education trade union. She has previously worked in the trade union movement as a senior research officer with the financial trade union now known as Accord. Following that she was assistant general secretary of the Nationwide Group Staff Union.