Kevin Wilson looks at the Ford sewing machinists’ strike of 1968 and the wider campaigns for equal pay since the nineteenth century, and highlights LSE’s rich collections in this area.

Kevin Wilson looks at the Ford sewing machinists’ strike of 1968 and the wider campaigns for equal pay since the nineteenth century, and highlights LSE’s rich collections in this area.

Fifty years ago – on 7 June 1968 – a landmark event in UK labour relations occurred, which directly contributed to the passing of the Equal Pay Act in 1970. The Ford sewing machinists, who made car seat covers, ceased production after a pay regrading favouring male workers at the Dagenham factory. The female sewing machinists had been downgraded from Category C workers (skilled production jobs) to Category B (less skilled production jobs), which meant the sewing machinists would earn 15% less than their male colleagues. The strike encouraged others at Ford to strike (including at the Halewood plant in Merseyside), completely halting car production whilst the dispute lasted.

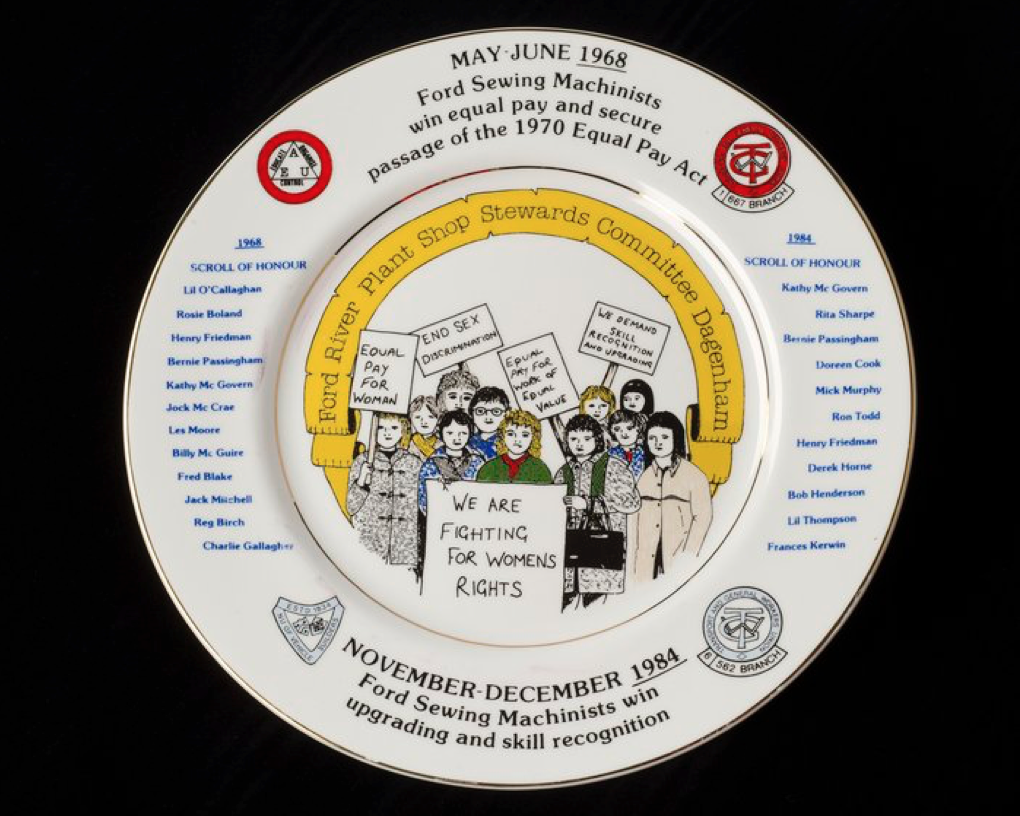

After three years of industrial action, The Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity, Barbara Castle, intervened, and although their pay was increased to 92% of the male rate (from 85%), they never received their Category C grade. It took 16 years for the women to be regraded completely, after further industrial action in 1984 when female sewing machinists again went on strike for six weeks. After an independent arbitration panel found in their favour, Ford agreed to regrade the women as skilled workers. A key object within the Women’s Library, held at LSE Library, is a commemorative ceramic plate that was produced to recognise the industrial action of 1968 and 1984.

Credit: LSE Library.

Credit: LSE Library.

Barbara Castle and the Equal Pay Act (1970)

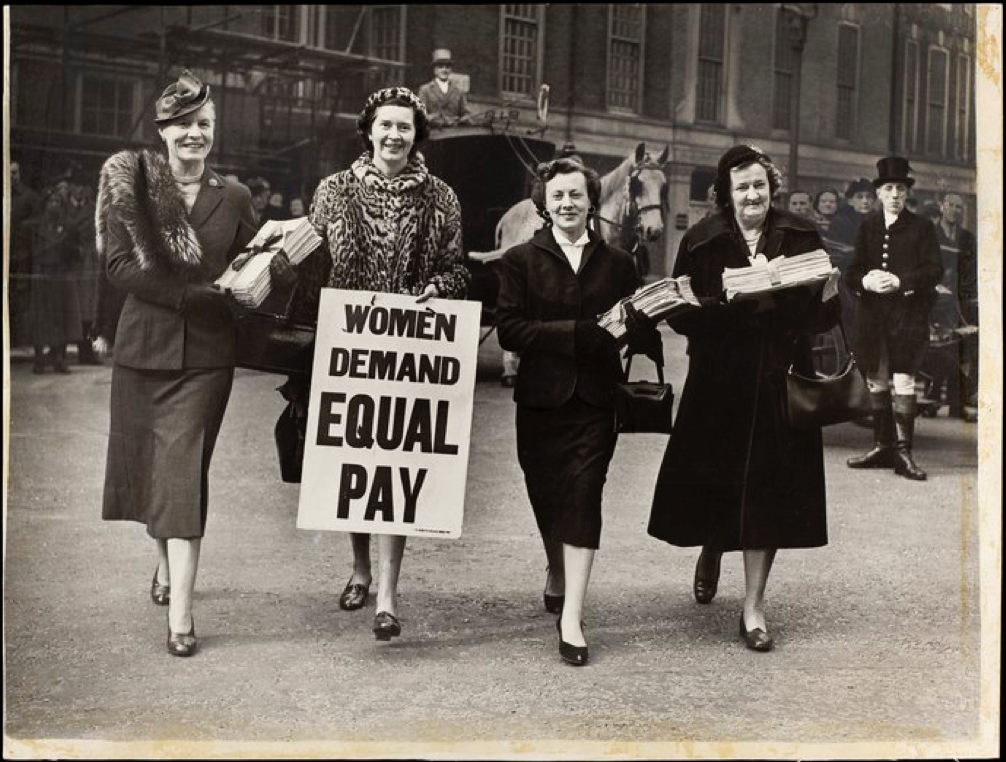

For Castle herself, equal pay for women had been a long term goal. The below photograph in the library’s archives, from 1954, is of a delegation that presented a petition to 10 Downing Street following the National Federation of Women’s Institutes resolution on Equal Pay for Equal Work, which was first passed in 1943 (Castle is third from the left).

Credit: LSE Library.

Credit: LSE Library.

Castle’s perseverance with the Equal Pay Act ensured there were dramatic effects on pay and grading (and some of her employment-related proposals, such as the abandoned white paper ‘In Place of Strife’, were controversial, causing intense divisions within the Labour Party). The Act eliminated separate lower rates of pay according to gender, although the law was sufficiently ambiguous to allow some employers to create different job titles for women to ensure their pay did not reach parity with men. However, full–time women’s average earnings rose from 72% to 77% compared to men’s by 1975. The papers of Baroness Beatrice Nancy Seear consist of items relating to the implementation of the Act, including submissions from prominent women’s organisations, and an annotated copy of the Bill.

Violet Markham and Clementina Black

The LSE Library holds a number of archives highlighting the cause for equal pay and treatment in the workplace from late 19th century onwards. This includes Violet Markham’s personal papers, the correspondence and papers of the Women’s Industrial Council, a strand of the Women’s’ Library Archives focussing on women’s employment organisations, and oral histories within the Fawcett Collection that explore the lives of pioneering career women who made their mark in traditionally male areas of the workplace.

Violet Markham was a politically active philanthropist, calling for widening employment opportunities and higher wages for women. Markham enjoyed several decades of public service, culminating in her appointment as Deputy Chairman of the Unemployment Assistance Board in 1937; “probably the most important administrative post up to that time that had been held by a woman”.

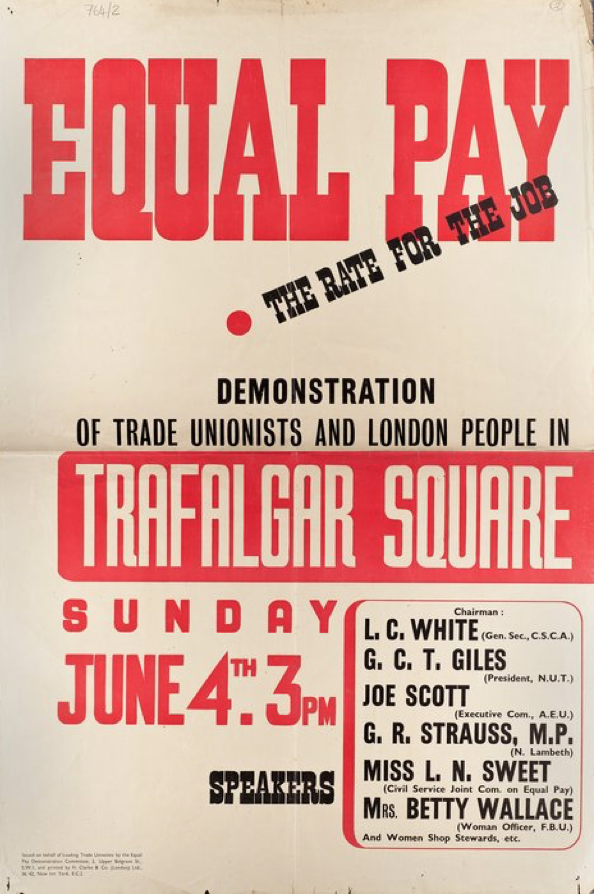

Clementina Black, on the other hand, was very involved with the emerging trade union movement and with issues faced by working-class women. One of only three female delegates at the Trades Union Congress in 1888, Black proposed that women workers should be paid the same as men for doing the same work. Although the motion carried, it took several decades for this inequality to be redressed. An Equal Pay demonstration from 1944 reiterates how little progress had been made.

Credit: LSE Library.

Credit: LSE Library.

Clementina Black became Honorary Secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League and founded the Women’s Industrial Council, whose correspondence and papers are held at LSE Library. Black was also active in the Fabian Society, campaigned for a legal minimum wage, and was also involved in the early suffrage movement.

The Women’s Liberation Movement and Sheila Rowbotham

The 1960s had witnessed social changes such as the introduction of the contraceptive pill (1961) and the Abortion Act (1967), and of course the issue of equal pay was in the public eye because of the Ford machinists strike. These events culminated in the first National Women’s Liberation Movement conference, held in Oxford from 27 February to 1 March 1970. The conference discussed issues affecting women such as equal pay and equal education as well as employment opportunities. More conferences took place across the decade, whilst further legislation passed during those years, such as the Sex Discrimination Act and the Employment Protection Act (both 1975) further protected the rights of women.

LSE Library holds both the Women’s Liberation Movement papers and its conference papers. Sheila Rowbotham was involved in the Movement and her papers include correspondence and campaigning material, in particular for the Night Cleaners Campaign to improve the working conditions and pay for office cleaners. Recognising women’s skills and abilities as equal to men’s, and to be paid accordingly, was very much part of this campaign. The Sisterhood and After Research Team at the British Library highlights further industrial action across the 1970s, as workers fought for their rights “regardless of gender, ethnicity and class”.

Credit: LSE Library.

Credit: LSE Library.

Equal Pay in 2018

Despite more than a century of campaigning, the issue of equal pay has still not been satisfactorily resolved. The latest initiative to achieve equal pay was in April 2018, when the government announced that companies with more than 250 employees (around 9,000 companies or organisations) must publish their gender pay gap data. Office of National Statistics data suggests that on average, men earned 18.4% more than women in 2017 and 78% of companies paid men more than women. The ONS has also produced an accompanying article that analyses the gender pay gap in the UK, to give the data context. Although the Equality and Human Rights Commission is responsible for ensuring that employers publish these figureadms, whether companies or organisations can be punished for a wide gender pay gap is less certain.

________

Kevin Wilson is the Academic Liaison and Collection Development Manager at LSE Library.

Kevin Wilson is the Academic Liaison and Collection Development Manager at LSE Library.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

1 Comments