Exam results are the latest issue to get the ‘postcode lottery’ rhetoric; however, Keith Clements from the National Children’s Bureau argues that attention must also be paid to what happens to children before their first day in class.

Exam results are the latest issue to get the ‘postcode lottery’ rhetoric; however, Keith Clements from the National Children’s Bureau argues that attention must also be paid to what happens to children before their first day in class.

Nicky Morgan was right to point out disparities in academic attainment across the country in her recent speech on ‘one nation education’. Of course, the injustice of children lagging behind their peers – and the implications this has for their long term prospects – for being born in the ‘wrong’ postal code, is something that few would seek to justify.

However, ignoring the wider context in which schooling takes place will severely limit the effectiveness of any strategy to tackle inequalities. The ‘postcode lottery’ is an oft-cited concept in British public policy. In our recent report Poor Beginnings the National Children’s Bureau highlighted another example of birthplace pot luck, this time in variations in young children’s health and development as they start school. Its findings may offer some clues to the causes of the different levels of attainment that Nicky Morgan finds so shocking.

To give an example, while less than half of all young people in Leicester get 5 A* to C grades including English and maths, the city also has the lowest rates of children reaching a good level of development by the end of Reception, as well as high rates of tooth decay, and obesity in young children.

Startling local variations in early health and development

Local variations are just as wide for these early life outcomes as they are in academic attainment. A five year old in Barking and Dagenham is over two and a half times more likely than a child in Richmond upon Thames to be obese. This puts them at greater risk of asthma, sleeping difficulties, and emotional and behavioural problems during childhood, as well as a higher chance of diabetes and cardiovascular disease later in life.

Meanwhile a child under the age of 5 on the Isle of Wight is over four times more likely to be hospitalised with an injury than one of their peers in Westminster. It should not need explaining that injuries are something to be avoided, but it is worth remembering that severe injuries are also associated with a range of health and psycho-social problems in both the short and long term as well the immediate physical impact on a child. Many of these injuries could be avoided through better safety in the home.

Regional variation and the link with local deprivation: wider context is key

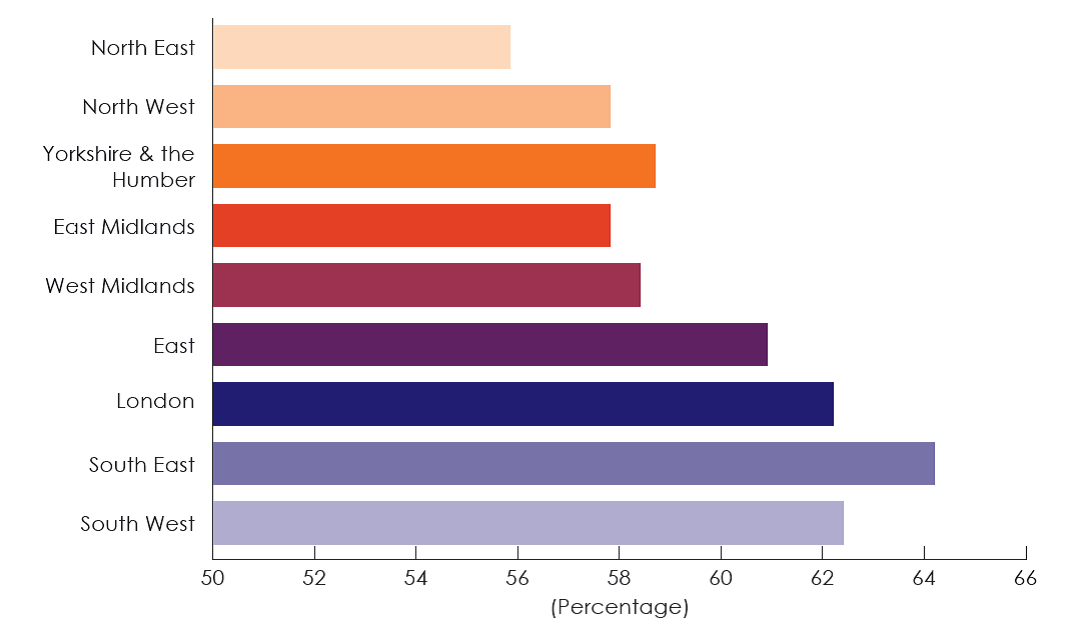

Perhaps not surprisingly, there are notable regional variations in young children’s health and development. There is some degree of a North-South divide in all outcomes considered by the Poor Beginnings report but this is most notable in the proportion of children achieving a good level of development with the North East seeing just 56 per cent compared to 64 per cent in the South East. This is measured through an assessment carried out by teachers at the end of reception year looking at physical, social and emotional development, communication and language as well as their early progress in maths and literacy.

Proportion of children achieving a good level of development by the end of reception, by region (2013/14)

[Source: Department for Education (2014)]

Obesity, tooth decay, injuries and poor development are all linked to poverty at an individual level. So no surprises for guessing how things look when we consider the level of deprivation in each local authority.

If all local authorities had the same outcomes as the 30 least deprived there would be:

- Nearly 10,000 fewer obese children in reception class

- Nearly 35,000 fewer five-year olds with tooth decay

- Over 5,000 fewer cases of early childhood injury

- Nearly 12,000 more children achieving a good level of development by the end reception.

Knowledge and political will

There are, of course, variations that go against the grain. In the North West, Halton’s rate of obesity is about a third higher than Salford’s, despite very similar levels of deprivation. And in the Midlands, Birmingham has more children achieving a good level of development than Nottingham despite being more deprived. There are several other examples like this, emphasising that we should not underestimate the potential of either ‘poor kids’ (which Nicky Morgan has accused her Blairite predecessors of doing) or more economically challenged communities.

But raising expectations is not a solution in itself. We need to understand why some areas have better outcomes than others despite similarly challenging circumstances. Local government and health bodies must be able to learn from these lessons and have the political will to make the requisite changes. National Government can support them in this, not least by facing up to the regional differences in prosperity that are the driving force behind most of these variations.

It would be wrong to suggest this is a quiet backwater of public policy. Some standard tricks have at least been tried when it comes to making progress – or be seen to be making progress – on a perennially intractable problem. The division of responsibilities is being changed – local authorities took over children’s public health from the NHS in October and devolution of more health powers to city regions is being trialed. Measurements are potentially being recalibrated – with collection of information on children’s development being replaced with benchmarking of maths and literacy.

Local authorities are, in theory, well placed to take on young children’s health – with their roles in childcare, housing and planning just a few levers that they can bring to the table. However, observers have noted that the schools agenda is being pursued quite differently, with local authorities being cut out by Academies which have direct contracts with the Education Funding Agency (part of the Department for Education).

Another, related, and perhaps more telling, difference is funding. While there is a commitment to protect the schools budget alongside that of the NHS, the devolution of public health to local authorities meant that a £200 million cut has recently slipped through largely unnoticed – being described by the Treasury as ‘Non-NHS’. The lack of impassioned speeches by Ministers about health inequalities is not the only sign, it seems, that this area is not receiving the political priority that they should.

This needs to change. Schools may be the ‘engines of social justice’, but they will stall if children do not arrive there healthy and ready to learn.

__

Please note: this article represents the views of the author and not those of the British Politics and Policy blog nor of the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

__

Keith Clements is a Policy Officer at the National Children’s Bureau. This blog draws on research carried out for a recent report entitled Poor Beginnings – Health inequalities among young children across England. You can follow the National Children’s Bureau on twitter @ncbtweets.

Keith Clements is a Policy Officer at the National Children’s Bureau. This blog draws on research carried out for a recent report entitled Poor Beginnings – Health inequalities among young children across England. You can follow the National Children’s Bureau on twitter @ncbtweets.

(Featured Image Credit: Number 10 CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)