The outcome of Brexit is likely to be less investment because of less policy credibility – regardless of what type of relationship with Europe is agreed. What makes Britain particularly prone to economic policies that are not credible is its parliamentary system, writes Christopher Gandrud and demonstrates how UK investment worked before and after the UK joined the EU. He argues that to avoid going back to the less prosperous years, constitutional reforms will be necessary.

The outcome of Brexit is likely to be less investment because of less policy credibility – regardless of what type of relationship with Europe is agreed. What makes Britain particularly prone to economic policies that are not credible is its parliamentary system, writes Christopher Gandrud and demonstrates how UK investment worked before and after the UK joined the EU. He argues that to avoid going back to the less prosperous years, constitutional reforms will be necessary.

For much of the post-1945 period, the British economy was often described as the “sick man of Europe”, suffering from a “British Disease”. The symptoms were low investment and low economic growth. British Parliamentary sovereignty, in the context of party competition between ideologically polarised parties, made it difficult for the UK to credibly commit to investor-friendly policies – in other words to make promises that were believable. With less credible commitments there was less investment and the economy grew less.

This began to change in the 1970s and 1980s when upon joining the European Economic Community, Britain accepted external constraints on such policymaking, while a cross-party economic consensus on investor-friendly policies also developed. Both events improved the credibility of policies and of investment incentives.

Credible commitments before Brexit

Britain’s sovereign Parliament faces few checks and balances: once a government is in power, there are few hurdles to implementing their policy agenda. Parliamentary sovereignty also means that it is difficult for any one government to commit to their policies, as subsequent governments have the power to overturn them. So the system is susceptible to reduced credibility.

Despite considerable continuity in its domestic parliamentary institutions, post-war Britain had two very different credible commitment periods. The first – 1945 to mid-1980s – had weak commitments. The system was comprised of a fusion rather than separation of powers, by the power of each parliament not to be bound by its predecessors, and by the tensions created by polarised party politics. In such a system, where parties with greatly opposing views on economic policies but have reasonable chances of forming governments, credibility is reduced.

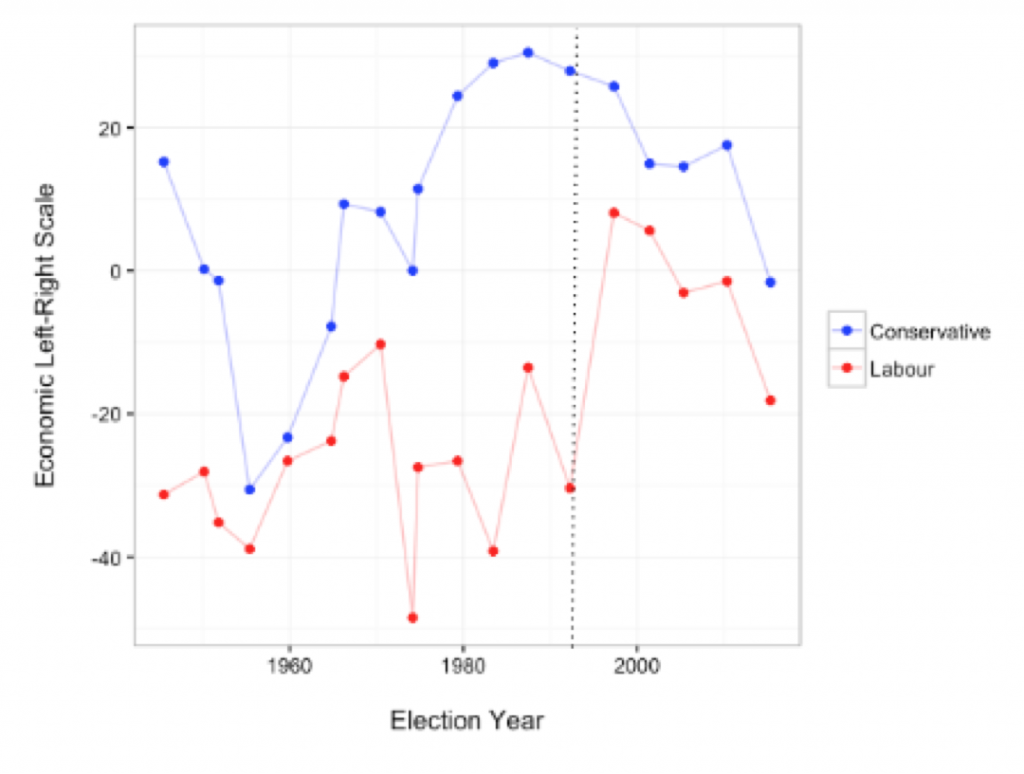

The second period – mid-1980s to 2016 – was a notable break in that the UK was able to make much stronger commitments. The key differences were (a) the degree of polarisation between the main political parties on investor-friendly policies had declined and (b) the imposition of external constraints – primarily the European Single Market – changed such policies. The degree and type of political polarisation over these two periods is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: UK Major Party Left-Right Orientation Based on Party Manifestos (1945-2015)

Negative values indicate more left-leaning policy positions. Data from Volkens et al.

Negative values indicate more left-leaning policy positions. Data from Volkens et al.

During the strong commitments period, polarisation declined significantly and did so through the formation of a cross-party consensus on investor-friendly policies, especially with the creation of New Labour from the mid-1990s. Tony Blair’s government quickly moved to commit to the previous Conservative government’s investor-friendly policies; it even went further by making the Bank of England politically independent. This enhanced the credibility of its price stability mandate.

Another notable feature of the strong commitments period was Britain’s joining the European Economic Community in 1973: the EEC increasingly pursued investor-friendly policies that would bind UK governments, a notable one being the Single European Act of 1986, which laid out the foundations of the Single Market. This committed the UK to allowing free trade in goods, capital, services, and labour in a significantly larger market, thus increasing the returns to investing in the UK.

Though the EU legislative process evolved over this period, it certainly was more strenuous than the UK’s. Changing the rules required some mixture of agreement from the European Commission, other member states, and the European Parliament. In so doing, it would be difficult for the UK and other European countries to make policy choices that inhibited business access to the much larger European market.

The level of business investment in the UK over the post-war period roughly corresponds to these two credible commitment periods. In the weak commitment period, business investment in the UK was relatively low at around 9 per cent of GDP, and lagged behind other European countries (Alford 1993, 8).

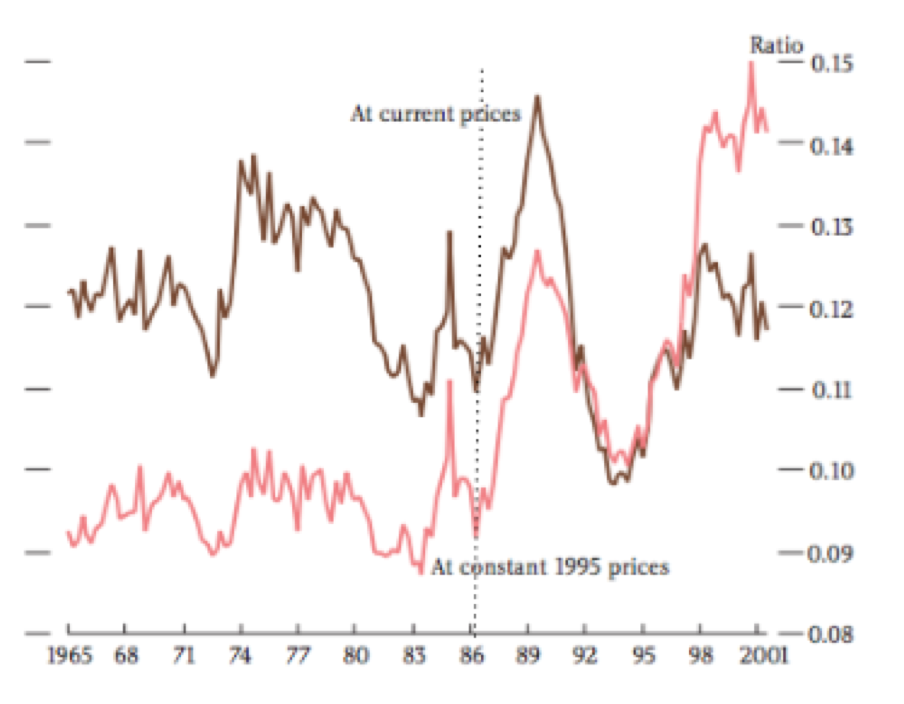

Business investment increased substantially from the mid- to late-1980s, almost exactly the point of the introduction of the Single European Act and the development of a cross-party consensus on more pro-market policies. Though investment clearly declined during times of financial market stress, such as the Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis in the early 1990s, the strong credible commitment era is characterised by a higher average level of investment. For example, foreign car companies increasingly invested in the UK in large part because they believed that doing so would give them access to the Single Market.

Figure 2: United Kingdom Business Investment to GDP Ratio

Reprinted from Bakhshi and Thompson with dotted line added in 1986. Based on ONS data.

Reprinted from Bakhshi and Thompson with dotted line added in 1986. Based on ONS data.

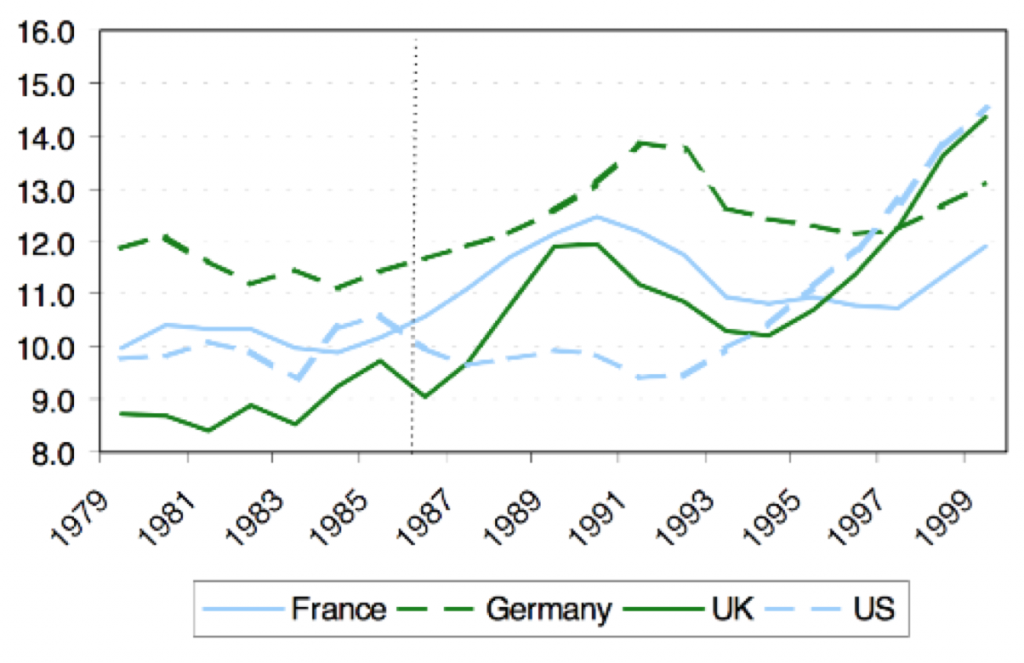

The increase in investment in this period was not limited to the UK, but common across at least the large EU economies as we can see in Figure 3. In contrast, investment in the United States, which was outside of the EEC, did not change at this point, suggesting an effect specific to the creation of the Single Market.

Figure 3: Business Investment as a Share of GDP (constant 1995 prices)

Reprinted from Bloom and Bond with dotted line added in 1986. Based on OECD data.

Reprinted from Bloom and Bond with dotted line added in 1986. Based on OECD data.

Credible commitment conundrum after the referendum

The narrow Brexit vote returns the UK to a weak commitments path. Leaving the EU and possibly even the European Economic Area would remove external constraints that enhance the credibility of UK commitments. Even if the UK does not leave the EU, the vote has re-exposed fundamental credible commitment problems created by Parliamentary sovereignty.

The large post-Brexit constitutional overhaul, including reducing or removing commitments made to maintain free trade within Europe, will likely be made based on a majority vote in parliament for a referendum, 37.4 per cent of the electorate voting for leave in the referendum, and then the decision of a prime minister without a personal electoral mandate. In theory, the process could be even simpler, as Parliamentary sovereignty would have allowed the decision to be made by a simple Parliamentary majority. Such a low requirement for such a large change to economic policy makes it difficult for the UK to commit to future policies.

Additionally, it appears likely that in the near-term there will be considerable polarisation in the UK exacerbating Parliamentary sovereignty’s credible commitment problem. The British political party system is also facing upheaval with current party leaders: Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn are ideologically far from each other. Many of the policy responses to the Brexit vote are likely to further exacerbate this polarisation.

There is little consensus among supporters of Brexit of what form it should take. How much should trade with the EU be privileged over immigration controls? What type of free trade should be pursued and with whom? In such a policy environment, and with so few checks on government power, we can expect “policy cycling”: sweeping policy changes which undermine the credibility of any particular government’s commitments. This is likely to suppress investment and growth in the future regardless of the type of Brexit that is decided in the near-term.

One notable difference from the previous weak commitments period is that the Bank of England is formally politically independent. But even the credibility of this formal commitment is weak in the UK, as Keefer and Stasavage find, the credibility of central bank independence is influenced by the number checks on government. Especially within this UK context, recent heated criticism of the bank by governing party members is particularly harmful to its credibility.

One route forward would be to commit to a different set of international rules, such as those of the European Economic Area or World Trade Organization. However, these commitments would not be credible due to the underlying weaknesses in domestic political institutions and politics. To address these problems, especially in the absence of external EU constraints, the UK needs to change its domestic political structures. Such reforms could include requiring parliamentary supermajorities and/or supermajorities of the four nations to pass major constitutional changes.

But creating institutions that would enhance Britain’s policy credibility in the context of polarised politics generates a conundrum. Changing institutions creates incredible commitments because those who are given the ability to change the rules would use this ability to entrench their position or, just as importantly for credible commitments, opposing sides would anticipate them to do this. They will have a problem credibly committing to creating rules that all sides accept. Because of this, there will likely not be support to start the constitutional reform process. If reforms are passed, currently opposing sides may overturn them when they come to power.

Resolving the credible commitment conundrum will be difficult, but regardless of how Brexit proceeds, it is needed to avoid a relapse of the British Disease.

____

Christopher Gandrud is Lecturer of International Politics at City University London.

Christopher Gandrud is Lecturer of International Politics at City University London.

Well! Rarely is it so clearly been argued that democracy is bad for business and that consequently the voters should only be allowed to choose between nigh-indistinguishable party platforms. Democracy — it’s the British Disease.

Interesting but not convincing. There are simply so many variables that determine the levels of investment by businesses that what goes on in high politics is only one among many. Short termism has always been a characteristic of UK investment weakness and this has persisted even in time of very friendly policies towards business investment.

Indeed you note the investment by the car industry, which is entirely foreign owned largely because indigenous owners refused to invest where foreigners saw an opportunity.

The fact that the rich of Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa see UK property as a good place to bank their money (no doubt some of it ill gotten) shows a sentiment that UK is politically stable for investment generally.

I do not disagree with your analysis, only in how much of the overall picture it paints.

Interesting analysis. However now that we have entered a period in which sustainable development is a higher priority than economic growth by itself, then economic policy consensus does require to be replaced with economic policy antagonisms in order to democratically reform or at least provide the democratic possibility to reform the economic growth imperative into a sustainable development imperative.

Bearing in mind that the UK has sufficient material wealth which just needs to be shared appropriately and that economic activity needs to be differentiated between low, medium and high impact in order to reduce our ecological deficit then economic growth must now be constrained by social inclusion and environmental protection. This policy shift can only occur through policy independance that is not externally constrained.