Throughout the short campaign, this blog will be publishing a series of posts that focus on each of the electoral regions in the UK. In this post, Ron Johnston discusses the key things to look out for in the South West. He suggests that it is unlikely that there will be substantial change – with Labour the main beneficiary of any shifts.

Throughout the short campaign, this blog will be publishing a series of posts that focus on each of the electoral regions in the UK. In this post, Ron Johnston discusses the key things to look out for in the South West. He suggests that it is unlikely that there will be substantial change – with Labour the main beneficiary of any shifts.

See electionforecast.co.uk’s predictions for the South West here.

After the 2010 general election, almost every constituency in England fell into one of three types:

- Those where the Conservative and Labour parties occupied the first two places and the Liberal Democrats came a relatively poor third;

- Those where the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties occupied the first two places and Labour came a relatively poor third; and

- Those where the Labour and Liberal Democrat parties occupied the first two places and the Conservatives came a relatively poor third.

Of the 55 constituencies in Southwest England, 13 fell in the first group, 40 in the second, and just two in the third. Each group presents a different set of challenges in the current campaign.

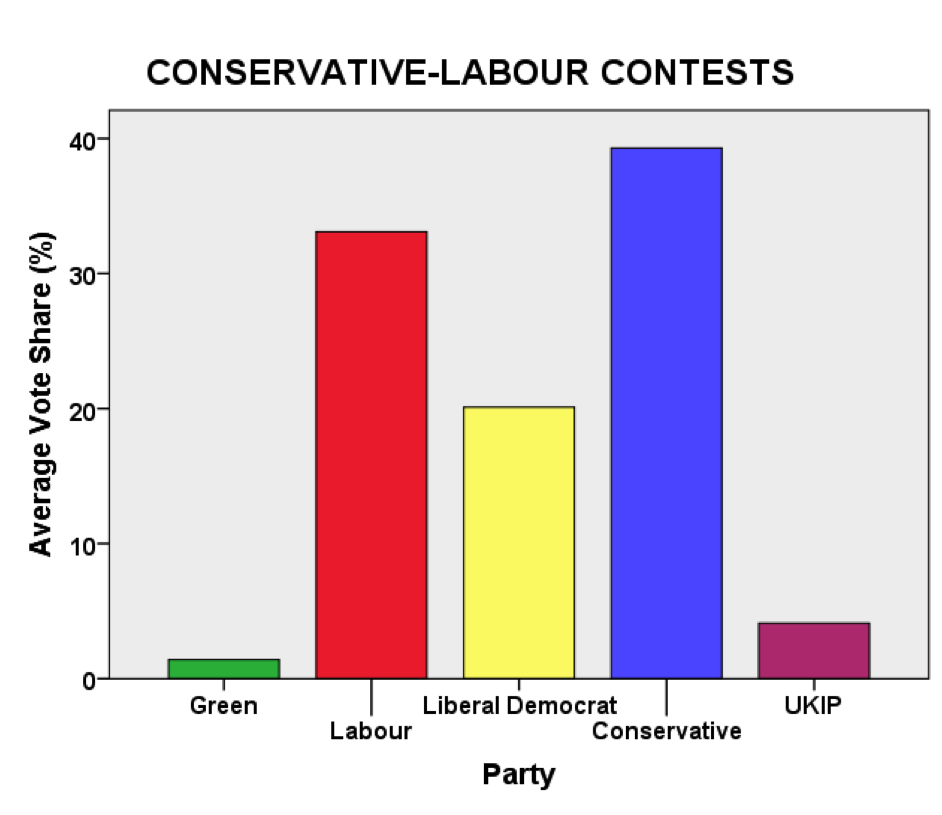

Looking first at the Conservative-Labour contests, the first graph shows each party’s average vote share across the 13 seats in 2010, illustrating the Liberal Democrats’ considerable distance behind their opponents.

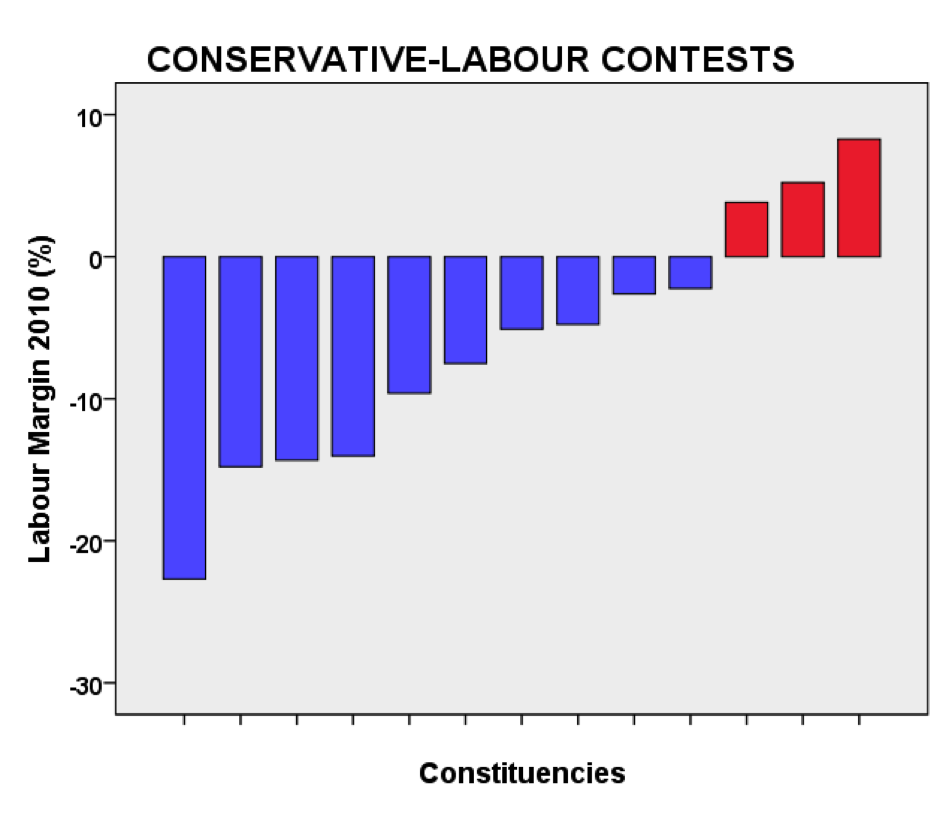

The second graph shows the margin of victory/defeat for the Labour candidates in each of the 13 seats. Labour won just three of them (Bristol East, Plymouth Moor View, and Exeter) and can reasonably be sure of victory there again. In six others, the Conservative margin of victory was less than ten percentage points, creating strong Labour expectations that they are winnable – especially if their candidates can pick up substantial proportions of the votes that went to the third-placed Liberal Democrats last time and there is also a considerable leakage from the Conservatives to UKIP (which however has a weak regional and local base on which to base its campaigns compared to other parts of the country).

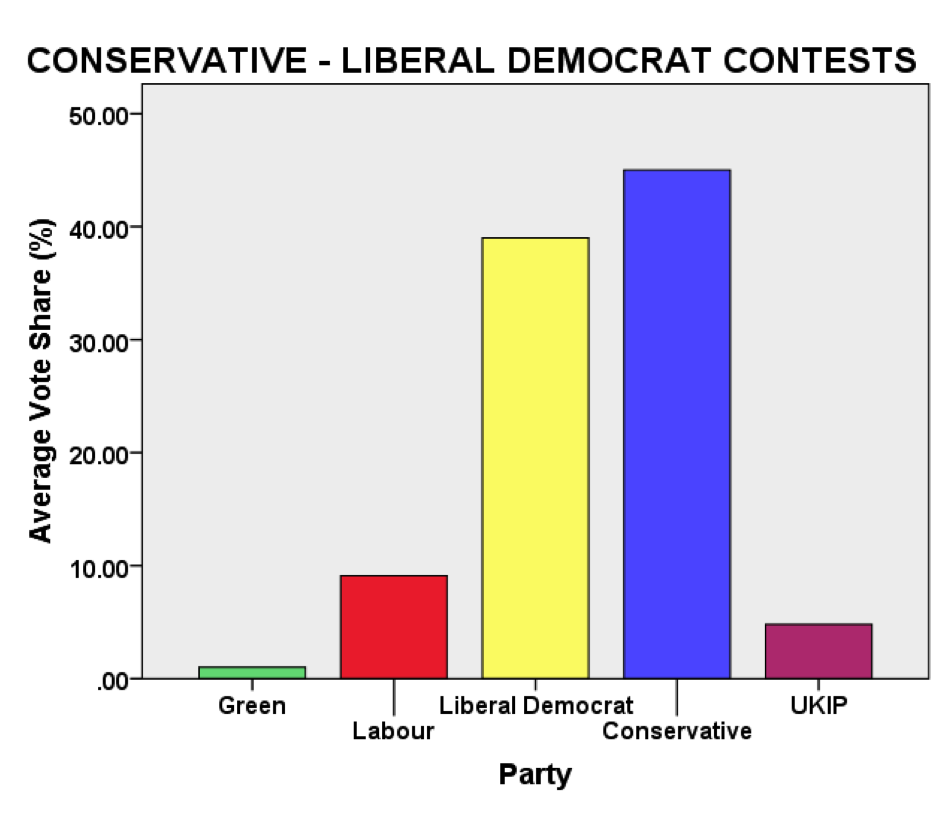

The two largest parties dominated Conservative-Liberal Democrat contests in 2010, with Labour on average coming a very poor third – as the third diagram shows. The Conservatives will be expecting to hold all 26 of the 40 seats they won then, including the eight where victory was achieved by very small margins – unless there are many defections to UKIP and the Liberal Democrat vote holds up well. Only one of those seats – Bristol Northwest – offers any real possibility of the Labour candidate coming from third place to victory by winning over a very large share of the 2010 Liberal Democrat votes. (Many of those Liberal Democrat votes then will have been cast by students who no longer live there. Across most constituencies in the Southwest there is a solid Liberal Democrat core vote, but in Bristol – as elsewhere in university cities where the Liberal Democrats performed well in 2010 – there is only a small core because of the nomadic student vote. The students who register – if they do – and vote in 2015 – if they do – will not be those who were there in 2010 and were won over by the Liberal Democrat pledge on tuition fees. Labour and the Greens have been working hard to attract new student voters to their causes.)

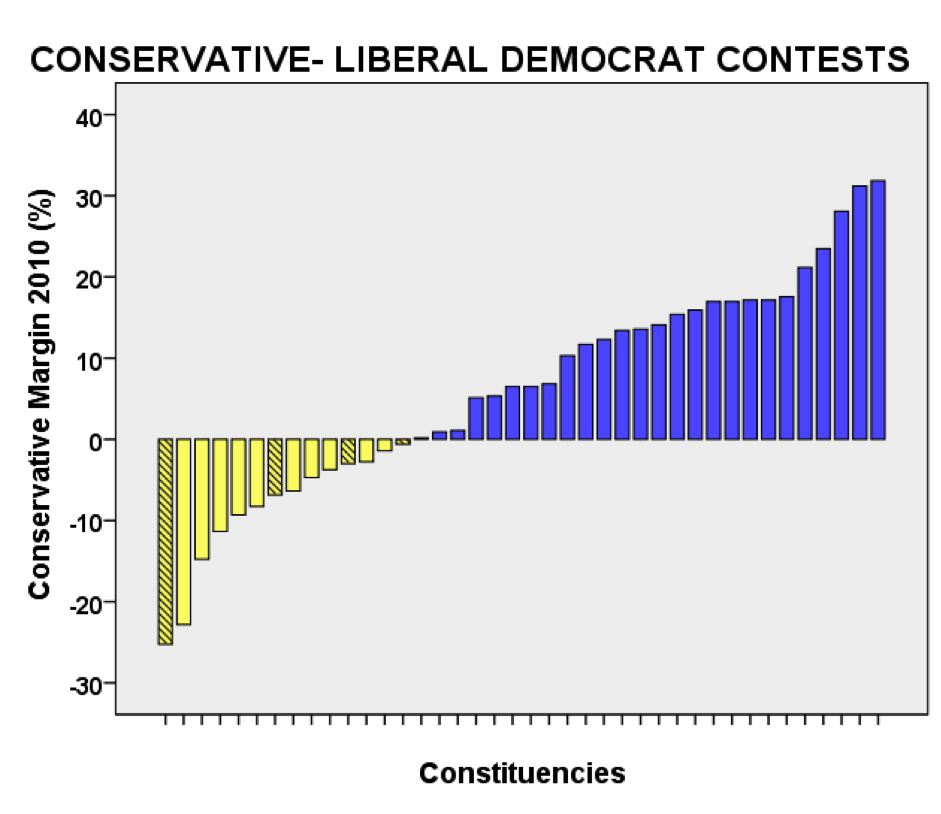

Of the 14 seats in this group currently held by the Liberal Democrats, ten – as the fourth diagram shows – were won by majorities of less than 10 percentage points in 2010. The Conservatives will have high hopes of winning most of them – especially since the Labour base is weak, winning less than 10 per cent of the votes in all of those constituencies in 2010. The Liberal Democrats are expected to perform better than average where an incumbent MP is defending the seat – but in three of those ten constituencies (Mid Dorset & North Poole, Somerton & Frome, and Taunton Deane: shown by cross-hatching in the diagram) the incumbent is standing down, making them even more vulnerable to a Conservative gain. Of the seats with a retiring MP only Bath, with a 2010 majority of 25 percentage points looks safe for the new candidate. (Lord Ashcroft’s polls in late March suggested that several Liberal Democrat incumbents were likely to retain the seats they are defending, with around half of the electorate in those seats contacted by each of the parties during the last few weeks.)

Finally, the two Labour-Liberal Democrat contests are both in Bristol. Stephen Williams is defending a 20 percentage point majority for the Liberal Democrats in Bristol West and should retain the seat – although it is one of the Greens’ targets and they are campaigning hard. Bristol South is one of the closest in the region to a three-way marginal but the Labour candidate – Karin Smyth, a long-term Bristol resident and Labour party worker is replacing Dawn Primarolo – should retain it.

In 2010, the Conservatives won 36 of the region’s 55 seats, the Liberal Democrats 15, and Labour 4. The Conservatives could gain at least six from the Liberal Democrats, perhaps more, but lose as many as six to Labour. And so a possible outcome is:

- Conservatives – 36

- Liberal Democrats – 9

- Labour – 10

But look out for surprises. Will the Greens succeed with their intensive campaigning in Bristol West? Will most of the Liberal Democrat incumbents hang on against the national trend because of their party’s deep roots in much of the region? If the answers are yes, then Labour will be the clear beneficiary; if not, the Conservatives, despite losing some seats to Labour, could be the main beneficiary of a decline in Liberal Democrat support in one of that party’s traditional heartlands.

Finally, what of UKIP? It won’t win any seats in the Southwest – and almost certainly doesn’t expect to as its main targets are all in eastern England. But one of its major goals is to win enough support in many seats to put it in second place, providing a springboard for further advances at the next election – in 2020 at the latest. Will some of those springboards be in the Southwest?

Answering that question is not straightforward but some simple sums give an indication of the likely answer. If we assume that across all of the region’s constituencies UKIP gains 12 per cent of the votes cast in 2010 for the three main parties – 8 of them from the Conservatives, 3 from Labour, and 1 from the Liberal Democrats – then we get a situation commensurate with its current national polling situation. If that uniform swing took place, UKIP would come second in none of the 55 seats: indeed it would only come within 5 points of the second-placed party in just three – Christchurch, Devon Southwest, and the Forest of Dean.

Of course, UKIP’s advance will vary across the 55 constituencies, which may result in a second place – but almost certainly in a few seats only. Its prospects in this part of the country are poor.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol.

Apologies from the author – the vertical axes on the second and fourth graphs show the margins in 2010 NOT 2005