Launching the Labour party’s general election campaign on 5 January, Ed Miliband estimated that the Conservatives would outspend Labour by a ratio of 3:1. Recent media commentaries have suggested that the Conservatives are already attracting large sums in donations to the campaigns in their target constituencies. But is that much money being given? Ron Johnston, David Cutts and Charles Pattie examine the evidence.

On 28 October 2014, The Independent on Sunday carried an article by its Political Editor, Jane Merrick, entitled ‘Tories splurge cash to combat UKIP threat’. The story’s thrust was that, because of the growing UKIP threat to their chances of victory at the 2015 general election, the Conservatives were increasingly focusing their constituency campaigning – and the search for donations to fund those campaigns – on the seats they were defending, rather than on the 40 they had targeted as potential gains.

Ms Merrick published a further story on Sunday 21 December headlined ‘Dave’s dinners fund a third of Tory target seats’. This claimed that ‘nearly a third of donations’ to the party’s top 40/40 target seats (i.e. the 40 marginals it must hold along with the 40 where it must unseat the incumbent party in order to win outright at the 2015 election) came from attendees at David Cameron’s Leader’s Group events, at which – for an annual fee of £50,000 – individuals are invited to meet with him and leading Conservative Cabinet Ministers. Of those 80 constituencies, she claimed that donations from attendees at those events had provided the majority of the money received in the first nine months of 2014 in 30 of them; the only donations received in 15 were from such sources (what she termed ‘seats funded exclusively by rich donors’).

The second article’s subtitle stressed the implicit theme – ‘Critics accuse Prime Minister’s controversial rich donors’ dining club of buying the election’. Only a small amount of data was provided to sustain that case; the 40/40 seats had received £2,638,752 from such donors since the last election. The message was that, as an additional price for their access to senior Tories, Leader’s Group members were being encouraged to make donations to constituency parties where defeat in 2015 was a possibility – and as a consequence local campaigns there were well-funded. For the ‘privilege’ of attending the events, and whatever gains it might bring to them and their companies, individuals were providing substantial funds to enable the Conservatives to at least be the largest party in the House of Commons elected in May 2015.

But is that message borne out by a more careful look at the figures? We have analysed the same data used by Ms Merrick – the Electoral Commission’s register of all donations to political parties (either cash or non-cash) of £1,000 or more. We look just at the data for the first nine months of 2014 – those for the last quarter are not yet available – all of which we presume cover donations aimed at assisting the Conservative candidates’ local campaigns.

On one point, Ms Merrick’s argument clearly stands up. The Conservative party publishes the names of attendees at the Leader’s Group events, and 81 individuals are listed for 2014’s first three quarters (many attended more than one), of whom only 13 made no donation to the party during that period. The other 68 donated £9.3 million – but only just over £400,000 went to constituency parties, with the remainder going to the central organisation. Other donors – i.e. individuals and organisations not associated with the Leader’s Group events – gave a further £11.5 million, of which £2 million went to constituency parties. So those who met with the Prime Minister and his colleagues were certainly donors, but not particularly to the constituency campaigns; and they provided only a small fraction of the total donated to local parties.

Nor were they particularly generous. Candidate spending on constituency electioneering is unregulated until the official campaign starts in mid-December 2014. From then on they are restricted, in the average county and borough constituencies respectively, to £37,000 and £34,900 in the next three months, and then a further £15,000 and £12,900 respectively in the final weeks after Parliament has been prorogued – giving totals of some £52,000 and £47,800 over the two periods. (These maxima were increased to those levels by 22% and 24% respectively on what could be spent at the previous three elections, through a Statutory Instrument, in July 2015.)

Given those spending maxima, did the donors ensure that the candidates’ campaigns were well-funded before they started? Of the 40 most marginal seats the Conservatives are defending, 18 received no donations from attendees at Leader’s Group events – six of them were among the ten most marginal. A further 15 received only £2,500 each and just two – Corby (the 29th most marginal seat) and Watford (the 22nd) – received more than £10,000 each (£12,500 and £44,500 respectively). The donors certainly seemed to accept the party’s apparent strategy of focusing on the seats it was defending; of the 40 most marginal where it lost in 2010, 23 received no money from the attendees, and only one received more than £5,000 – a single donation to Exeter, the 31st most marginal constituency. But on average they provided very little – less than 10 per cent of the maximum that could be spent in the last four months before the election, even in those that received donations.

So what of the constituencies that, according to Ms Merrick, were ‘exclusively funded’ by Leader’s Group attendees, receiving nothing from other donors. There were five among the 40 most marginal seats being defended – and each (including the first and the sixth most marginal – North Warwickshire and Cardiff North) received just a single donation of £2,500.

In other words, in the first nine months of 2014 the Conservatives’ 40 most marginal seats won in 2010 were not awash with money from donors who attended David Cameron’s Leader Group events then. Indeed, when we look at who the donors were Ms Merrick’s conclusion looks even more like hyperbole. Of the £411,460 donated, £196,000 (48%) came from a single source – the United and Cecil Club, a long-term Conservative party supporter. Its Deputy Chairman, Christopher Fenwick (Fenwicks own eleven department stores), attended events in two of the three quarterly lists for 2014, hence its inclusion in this analysis. Apart from that Club (whose membership is unpublished), only four other donors provided more than £10,000 to constituency parties.

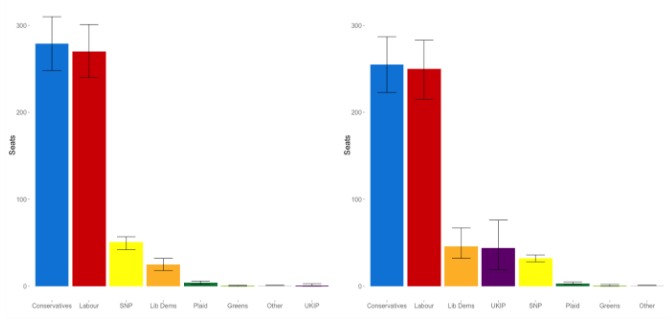

Of course, as the campaigning heats up these donors and others may be prevailed upon to give more, in return for access to the party leadership. But as yet it seems hyperbolic to claim – as do the titles, subtitles and implicit messages in Ms Merrick’s articles – that donors are splurging cash on the Tories’ local campaigns, to help them ‘buy’ the election. After all, of the £11.4 million received by the Labour party during the first nine months of 2014 (excluding its ‘Short Money’), £6 million came from the trades unions, including nearly £1 million that went to local components of the party’s organisational structure. The Conservatives got 75% of their total income of £20 million in the first nine months of 2014 from individual donors, and 8% of this went to constituencies. Labour got half of its money from the trades unions, and 17% of this went for local campaigns and other purposes. Is there really any difference between the two – other than where their money comes from?

Note: This article was originally published on our sister site, the LSE’s General Election blog, and gives the views of the author, and not the position of the British Politics and Policy blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Ron Johnston is Professor of Geography at the University of Bristol. Ron’s academic work has focused on political geography (especially electoral studies), urban geography, and the history of human geography.

Charles Pattie is Professor of Geography at the University of Sheffield, specialising in electoral geography.

David Cutts is a Reader in Political Science at the University of Bath. His research interests include party and political campaigning, electoral behaviour and party politics, party competition, ethnic minority political integration, and methods for modelling political behaviour and public opinion.

David Cutts is a Reader in Political Science at the University of Bath. His research interests include party and political campaigning, electoral behaviour and party politics, party competition, ethnic minority political integration, and methods for modelling political behaviour and public opinion.