Unpaid internships have become a way for graduates to gain experience in their chosen work environment and there have been calls for an increase in such practices in response to a weakening job market and rising youth unemployment. A recent article published in The Sunday Times entitled ‘A little bit of slavery does us all good’ provides a quintessential outline of this argument. But, as Paul Rainford explains, internships are often not open to all and in some cases are blatantly exploitative of young workers. A new way of valuing and widening opportunities for interns is needed, otherwise the coalition’s claim of fairness is an empty one and the UK will jeopardise its economic future.

Unpaid internships have become a way for graduates to gain experience in their chosen work environment and there have been calls for an increase in such practices in response to a weakening job market and rising youth unemployment. A recent article published in The Sunday Times entitled ‘A little bit of slavery does us all good’ provides a quintessential outline of this argument. But, as Paul Rainford explains, internships are often not open to all and in some cases are blatantly exploitative of young workers. A new way of valuing and widening opportunities for interns is needed, otherwise the coalition’s claim of fairness is an empty one and the UK will jeopardise its economic future.

‘Internships are accessible only to some, whereas they should be open to all who have the aptitude. Currently employers are missing out on talented people – and talented people are missing opportunities to progress. There are negative consequences for social mobility and for fair access to the professions’. So concluded Alan Milburn’s 2009 report into social mobility in the UK (see Unleashing Aspiration: The Final Report of the Panel on Fair Access to the Professions pp99-112). Elsewhere it notes the UK’s professions are becoming more socially exclusive and class background is still a powerful determinant of life chances. Career paths opened up to many on an informal basis – premised upon personal contacts or an ability to sustain oneself through a period of unpaid work – thus excluding many otherwise worthy and talented candidates.

The recent publication of the report on fairness (or lack thereof) in the UK by the Equality and Human Rights Commission – highlighting the latent inequalities that persist in our current system – must therefore have seemed sadly familiar to Mr Milburn in his new role as social mobility tsar for the coalition government. Laying the foundations for a more equal, more prosperous and a more open society with opportunities for all has to be the purpose of the coalition as it seeks to drag Britain out of the current economic malaise. This cannot be done if the current practice of unpaid internships persists.

The obstacles to be overcome are manifold, especially for younger generations dealing with the aftermath of the baby boomer years of plenty. Youth unemployment is at a record high, university graduates – often saddled with tens of thousands of pounds worth of debt – are entering a job market that lacks the capacity to absorb them all and businesses are lamenting key skills shortages and a lack of job-readiness amongst those that they do recruit.

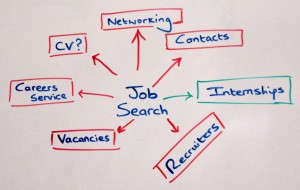

In this environment, internships are supposed to offer a transitional pathway into work that benefits both employers and job seekers alike. Interns are offered the chance to gain valuable experience and make contacts in their chosen sector, and employers are given an opportunity to better assess potential recruits and train them to their requirements.

In this environment, internships are supposed to offer a transitional pathway into work that benefits both employers and job seekers alike. Interns are offered the chance to gain valuable experience and make contacts in their chosen sector, and employers are given an opportunity to better assess potential recruits and train them to their requirements.

The Chartered Institute of Personal Development’s (CIPD) Labour Market Outlook Report estimated that more than one in five employers planned to hire interns between April and Sept 2010. However, only half of these placements were offered with payment at or above the level of the adult national minimum wage (NMW). As a result, interns paid less than this amount numbered around 128,000 in Britain during the summer months of 2010, with many interning full time for several months on end.

These unpaid internships are disproportionately concentrated in certain sectors including politics, media and fashion. Separate studies carried out by Unite and Skillset respectively estimated that there were around 450 unpaid interns working in Parliament and the constituency offices of MPs, and that 44 per cent of those working in media had to undertake a period of unpaid work before getting their current job.

There is also evidence of, for example, a major high street retailer – Urban Outfitters – advertising for a full time role in their planning department paying only expenses for a period of nine months, and the 1994 Group of British Universities – including high profile names such as Durham, York and St Andrews – offering unpaid administrative placements to recent graduates.

Those in favour of the status quo argue that cracking down on unpaid internships would prevent businesses from being able to offer any such opportunities, leaving young people with no route to gain much needed experience and further extending the cycle of unproductive joblessness. Julia Margo Deputy Director of the think-tank Demos – wrote an article for The Sunday Times entitled ‘A little bit of slavery does us all good’ (£) which put forward an argument to this effect.

By contrast, the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) released a paper in July of this year that took up the theme of the Milburn report by arguing that ‘many well qualified, talented and passionate people lack the resources to pay their own way through an unpaid internship’ ensuring that ‘certain industries and professions continue to be dominated by people from particular backgrounds, perpetuating inequality and dampening opportunities for social mobility’. The preponderance of internships based in and around London – 90% of all internships in law and 60% in banking – provides a further financial obstacle to those living outside of the South East and who may not have family and friends in the area with whom they could stay.

One of the major issues with regards to unpaid internships is the nebulous legal status of interns in general, with no clear category making the position distinct from volunteers and workers. Employers are seemingly taking advantage of this perceived grey area to circumvent responsibilities with regards to NMW legislation, with the Low Pay Commission going on record to state its concern at the level of ‘systematic abuse’ in this regard. Recent government guidelines have, however, attempted to clarify the role of volunteers as distinct from workers in the sense that the former ‘are under no obligation to perform work or carry out your instructions… and so can come and go as they please’.

Moreover, the IPPR report identified four common features of internships that would meet the criteria of being a worker. These include the length of tenure (usually between 3 months to a year – although a worker is entitled to payment no matter how long they are employed for), a time commitment (working set hours often full time), work expectations (performing specific pieces of assessed work to deadlines) and the contribution made to the organisation as a whole (meaning that the intern performs work normally undertaken by a paid member of staff).

In such cases the solution is simply a question of enforcing existing NMW legislation in full and ensuring compliance amongst employers. A landmark case of November 2009 saw the Reading Employment Tribunal rule that a woman who had been working on an expenses only basis in the Art Department of London Dream Motion Pictures Ltd was entitled to the NMW given the nature of her role and the tasks she was performing. This ruling emphasised that a worker cannot sign away their right to be paid, no matter how the position is advertised or the terms on which the individual enters a working arrangement.

The CIPD’s call for a new training wage for interns of £2.50 an hour should not detract from this process of NMW enforcement as it is clearly counter-productive to suggest that interns are somehow a sub-species to be denied basic working rights and the means to sustain themselves. Organisations and businesses who want to run internship schemes – given the benefits outlined above – need to work the attendant costs into their business plan and treat it as an investment just like any other.

For many of the larger employers, such costs could be comfortably covered by their annual turnover. For smaller employers for whom there will be little room for manoeuvre, further innovative solutions need to be found. A brief look back at the Milburn report provides a valuable starting point, with proposals ranging from internship support loans, to tax breaks for companies offering grants for interns from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and universities offering reduced rate – or free – accommodation for interns during vacations.

The IPPR builds on these suggestions to focus on the creation of Internship Training Associations who would be responsible for organising internship resource pooling – with employers organising placements collectively and sharing costs – and an emphasis on expanding opportunities and awareness in regions outside of London and the South-East. Sector-based outreach programmes could be organised through schools, universities and third sector groups and, combined with transparent advertising and application procedures, would help to overcome informational barriers and informal ‘who you know’ type processes.

The current trend of unpaid internships is a demoralizing and self-perpetuating cycle that entrenches unfairness and inequality. It is exploiting the extreme difficulties faced by – and the subsequent desperation of – young graduates and is a shameful indictment of the way in which the coalition’s theme of intergenerational fairness has not influenced actual business practices with employers flouting existing legislation and abdicating their responsibilities.

The UK cannot afford to waste the human resources at its disposal if it is to drag itself out of the current state of economic moribundity. As Milburn’s report noted: ‘It is not ability that is unevenly distributed in our society. It is opportunity… The UK’s future success in a globally competitive economy will rely on using all of our country’s talent, not just some of it’. Ending the practice of unpaid internships will provide a necessary step in this direction.

We are very interested in hearing from recent graduates who have had experience of the issues outlined above. Click here to respond to this post and leave a comment below or email the blog editors at Politicsandpolicy@lse.ac.uk

It’s rather demoralizing when you’re not being paid as an intern. Most staffers remember how they paid their own dues by working for free and so treat you well and with respect, offer advice and are patient with you. The only time I felt more like a certain standard was expected of me was when I was paid and then the workload did mount up. But I didn’t ever say I couldn’t cope so not sure if that would have made a difference. Because placements are so hard to get it’s very hard to feel like you can say no to a task, or show that you can’t cope. You are constantly aware that you need to make a good impression, be eager and network etc. I often felt a distinction between the people who I was working with: who realise how crap it is that you’re not being paid and often will try to make up for it where they can, for example sharing freebies from PR companies, telling you of vacancies or offering to be a reference for you which can make all the difference when applying for future jobs and those who I was working for: who take for granted that students will continue to compete for opportunities to work for free – which is true.

Certainly with regards to the media I don’t think that a lot of publications can afford to pay interns or increase staffing levels until the public start valuing news more and get back to a pay model rather than free online reading.

I might also add from work with young people, that they find the unpaid internship model highly exploitative. Is this something we want to teach as normal in our society?

I touched on this in a piece for CIF:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/dec/09/living-with-parents

I was rightly panned for much of the sentiment, however I completely agree with you,

For further comment on the ‘A little bit of slavery does us all good’ article click here:

http://internsanonymous.co.uk/2010/08/21/a-little-light-slavery-never-did-anyone-any-harm/